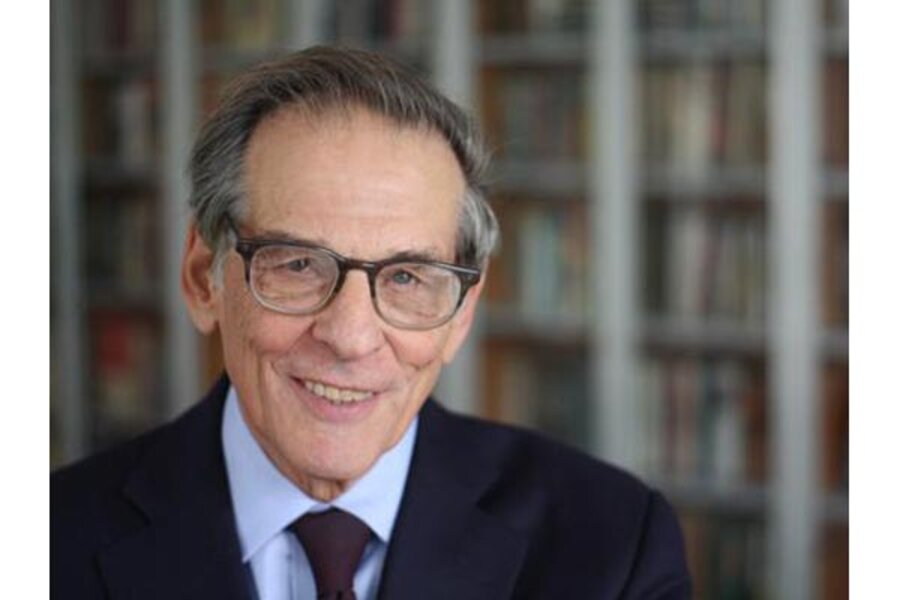

Catching up with award-winning LBJ biographer Robert Caro

DAVIDSON, N.C. — Robert Caro likes to say that he isn’t writing about Lyndon Johnson’s life. Instead, the 36th president’s tireless biographer says, he uses LBJ as a focal point to explore the use of power in the American political system.

That, of course, has led Caro to invest quite a bit of time and energy into the tiniest details of Johnson’s life. Nearly four full decades, in fact.

Caro, as with the best writers, lives by the maxim of show, don’t tell. The how and why obsess him, starting with a dirt-poor Texas Hill Country childhood and carrying through to the highs and lows of a White House tenure that includes staggering domestic achievements and debilitating foreign policy strategies and decisions.

Drawing on meticulous interviews with survivors and copious archival research, Caro, at 77, has become the standard-bearer for modern biography.

Four mammoth volumes into his LBJ biography, Caro keeps shedding new light on how Johnson leveraged a career in public office into a personal fortune; how he stole an election that could have ended his political career had he lost; and, most intriguing of all, how he counted votes, courted and confronted friends and enemies alike and, more often than not, got more than anyone considered possible in the halls of Congress.

On a recent winter night at Davidson College, a private liberal arts college near Charlotte, N.C., Caro delivers a lecture on Johnson just days after capturing the New York Historical Society’s American History Book Prize – and just before winning his third National Book Critics Circle Award on Feb. 28. Those prizes follow two Pulitzer Prizes (1975, 2003) and a National Book Award (2003). Last fall, he was one of five finalists for the National Book Award in nonfiction but lost to Katherine Boo.

“You know, when Winston Churchill was writing his famous biography of Lord Marlborough, someone asked him how it was coming along,” Caro told his audience by way of introduction. “And he said he was working on the fifth of a projected four volumes. I’m not comparing myself to Winston Churchill, but in this particular aspect, we’re in the same boat.”

It has been just under a year since Caro published “The Passage of Power,” the 712-page fourth volume in what was supposed to be a trilogy on the former president. Instead, Caro wrote a fourth installment and found that he would need at least one more to take LBJ’s story through Vietnam, his decision not to seek re-election in 1968 and, finally, his lost, embittered retirement.

Caro makes the talk-show and lecture rounds each time one of his books is published, but remains much more comfortable discussing his subject rather than himself.

The New York Times and a few others have dug up a few personal tidbits. Among the most repeated of late is Caro’s insistence on wearing a coat and tie to a private office he established in 1990, a 12-block walk from his home, as the Times reported. Last year, during an interview with CBS, Caro said he reports to his office in professional attire each day to trick himself into remembering that he has a job to do. His publisher, Alfred A. Knopf, doesn’t keep tabs on Caro, so Caro takes it upon himself to make sure he is productive.

For fans of the LBJ series, of course, there is another fear, one that readers of another epic biography – of Churchill, no less – know well. In 2004, William Manchester, the author of two popular and acclaimed volumes on Churchill, died. Before his death, he appointed a little-known journalist and friend to complete the final book. It was published last year and received mixed reviews.

But as Caro closes in on his 80th birthday, his readers need not despair: He remains spry. On this night, Joel Conarroe, a Davidson alum who has become a literary figure as former chair of the National Book Foundation and president emeritus of the Guggenheim Foundation, shares a few nuggets about Caro and his wife, Ina, a travel writer who also works with her husband as his research assistant.

Caro swims regularly to maintain his health and, judging by his appearance and remarks, remains invigorated by his pursuit of LBJ’s essence.

“Johnson was such a genius at using political power,” he says. “And bending Congress and all of Washington to his will. The greatest genius in the use of political power in America in the 20th century. It is endlessly fascinating watching him.”

Later, after signing books, Caro tells me in a brief interview that he doesn’t worry about finding answers and explanations to vexing historical issues.

With each volume in the Johnson biography, he says, a written account has always turned up. The key, Caro adds, is looking long and hard enough.

“The Passage of Power” offers several examples, most notably the section describing Johnson’s ascension to the presidency on Nov. 22, 1963. Though thousands of books have been written about the assassination of President John F. Kennedy that day in Dallas, none before Caro’s account ever looked at those historic events through the prism of the vice president: Johnson.

As Caro began his research, he knew that, at the time, the Secret Service required its agents to immediately file first-hand accounts after any incidents, minor or major, involving the security detail for the president and vice president. The recollections had to be completed the same day of the incident and mandated that all details, no matter how small, be included.

Caro requested the files on Johnson’s detail from the Secret Service and never received a response. Then, he recalled that LBJ almost always wanted a copy of everything. Hoping this extended to the Kennedy assassination and the motorcade that included Johnson, Caro asked the LBJ Library in Austin to check and see whether any of the 23 Secret Service agents’ reports were in their archives.

And, of course, they were, “bound together in the crudest way,” setting Caro on the course to tell the story from an entirely new vantage point. He interviewed John Connally before his death, eliciting more details. Connally, then the governor of Texas, was in the car with Kennedy that day. The secretary who made sure Johnson recited the oath accurately in the cabin of the plane after JFK was pronounced dead also spoke to Caro.

Through these and other accounts, Caro pieced together a fascinating portrait of the Dealey Plaza shooting and what Johnson experienced. Those events included Johnson being whisked to Parkland Hospital, the same place the mortally wounded president was taken. Secret Service agents hurried the vice president into a nondescript cubicle in the back of the hospital, where, for 40 minutes, no one knew whether Kennedy would live.

At last, Kennedy’s aide Kenneth O’Donnell appeared and, as Lady Bird Johnson would recall, the look on O’Donnell’s face made it clear the president was dead. Moments later, an aide walks in and addresses Johnson as “Mr. President,” confirming their suspicions. From there, as Caro puts it, LBJ instantly transformed himself from the hangdog vice president scorned by the Kennedy clique into the most powerful man on earth.

And, as Caro’s book details, over the next 47 days, Johnson would single-handedly resurrect the stalled legislative goals of the Kennedy administration, creating the Great Society and the War on Poverty with a stunning series of feints and maneuvers to put the White House in command of Congress.

The decisions setting the stage for those accomplishments were made in two hours and six minutes, the length of the flight from Dallas to Washington after LBJ takes the oath inside the cabin of Air Force One. Compare that with many modern political science experts’ contention that the two months between Election Day and Inauguration Day aren’t enough for an effective transition.

One photographer, Cecil Stoughton, followed Johnson to the airport while all of the reporters stayed at the hospital reporting on Kennedy’s death. Later, a few pool reporters would be summoned to witness LBJ taking the oath. As Caro tells it, he wanted to take readers inside the 16'x16' cabin where the transfer of power occurred, but he knew that his research had missed something crucial.

“I said, ‘I’ve talked to everyone [in the photo of Johnson taking the oath] who’s alive,’” Caro says, smiling. “But I had forgotten somebody: I had forgotten the photographer. I said, ‘Oh, God, I had years to do this, he must be dead.’”

Despairing, Caro looked in the national telephone directory and found a Cecil Stoughton in Washington. He called and Mrs. Stoughton answered the phone. Caro introduced himself.

Then, Caro says, “Mrs. Stoughton said, ‘Oh, Mr. Caro, Cecil has been waiting for your call …’ He told me a lot of things.”

Stoughton died in 2008, but not before he helped Caro provide a first-of-its-kind, fascinating perspective on what the new president experienced as the old one was shot and pronounced dead.

With such persistence and detail, it remains difficult to believe Caro can wrap up Vietnam, the deaths of Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert Kennedy, and the rest of Johnson’s turbulent tenure with one more book.

Munching on a tortilla chip, standing in an emptying reception hall, Caro gets a twinkle in his eye when I ask him – yet again – whether five books will be enough.

“I’m determined to do that,” Caro says.

-Erik Spanberg is a contributor to The Christian Science Monitor