Are books becoming less emotional?

A study published on Wednesday in Public Library of Science journal PLOS ONE discussed the results of a project in which British researchers searched five million digitized books provided by Google – about 4% of all books published since 1900 – to analyze the use of emotional language in books.

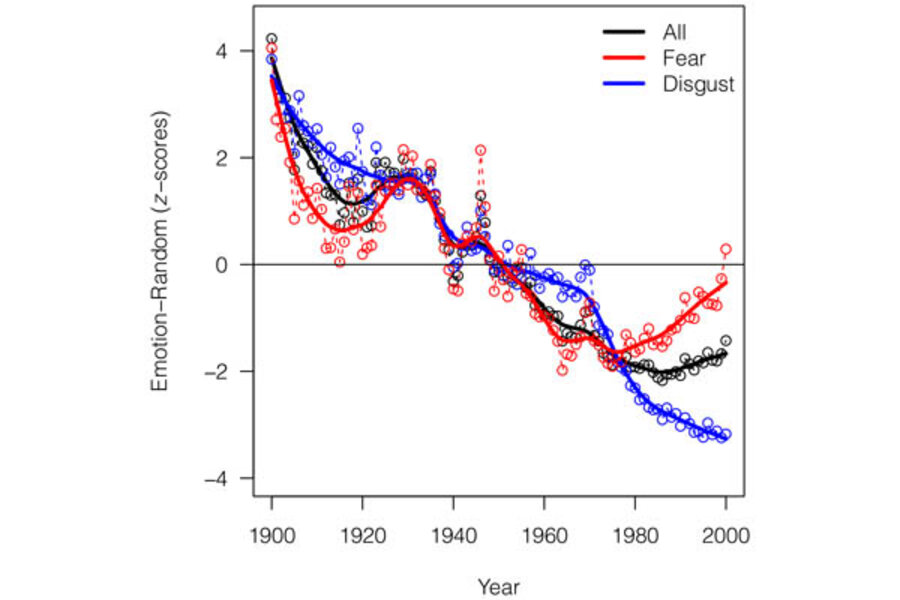

The surprising conclusion they reached: There has been a marked decrease in the use of emotional words that fall in six categories (anger, disgust, fear, joy, sadness, and surprise), with the exception of an uptick in fear since the 1970's.

Within that downward trend the researchers found that American authors use more emotional language than British authors.

The six categories had been used in an earlier study to analyze the public mood through U.K. Twitter accounts. That study showed that the frequency of mood-word usage on Twitter corresponded to real-life events like natural disasters.

This more recent study found evidence that mood-word usage seemed to respond to significant historical events as well. For example, words that correspond to sadness increased during the 1940's and throughout World War II. (On the other hand, World War I didn't seem to register)

According to this new study, there has been a definite split between British and American authors and their use of emotional language since the 1960's. Americans use more mood-words than the British, although both groups use fewer than they have historically.

The researchers say that they don't know exactly what happened in the 1960's, but that decade marks the period of a definite separation, both stylistically and emotionally, between British and American English.

“This relative increase [with respect to British usage] of American mood word use roughly coincides with the increase of anti-social and narcissistic sentiments in U.S. popular song lyrics from 1980 to 2007, as evidenced by steady increases in angry/antisocial lyrics and in the percentage of first-person singular pronouns (e.g., I, me, mine), with a corresponding decrease in words indicating social interactions (e.g., mate, talk, child) over the same 27-year period,” says the study. Information about changes in US song lyrics comes from a previous study done in 2011.

“We interpret this as a genuine decrease in the literary expression of emotion, but an alternative explanation could be that mood words have changed, rather than decreased in usage, through the century," explains the study. However, researchers said essentially, because the mood-words they used were more modern, they would have expected the data to skew towards an increase, which it didn't.

"While it is easy to conclude that Americans have themselves become more ‘emotional’ over the past several decades, perhaps songs and books may not reflect the real population any more than catwalk models reflect the average body."

As we've reported before, more and more scientists are using the tools and databases available to them to conduct massive studies of data, including studies of works of literature.

The British study concluded by praising the merits of big data analysis, and calling for more massive in-depth studies of sites like Twitter, Google, or blogs to study cultural evolution.