Mother's Day: why we should be thanking Louisa May Alcott and Marmee

Loading...

This weekend, as we pay tribute to mothers, we should remember not only the women who nurtured us – mothers, grandmothers, stepmothers, aunts, and teachers – but also the brave maternal figures of the past who paved our way. For centuries, female activists and writers struggled, often without public recognition, for the freedoms we enjoy today. In a nation replete with founding fathers, it seems necessary to acknowledge foremothers, too.

I’ve been inspired by Louisa May Alcott and her mother, the model for “Marmee” in Alcott’s 1868 classic, "Little Women." Alcott was childless but gave readers a good deal of motherly advice. Unlike most of her peers, Alcott believed girls should have the same opportunities as boys. Jo March, her teenage alter ego, promises to “do something splendid” with her life, “something heroic, or wonderful – that won’t be forgotten after I’m dead.” Alcott herself envisioned a future world in which women would have the same public rights as men, to vote, travel, speak out, and run governments. During her final decade, she used the bully pulpit of her celebrity to urge girls and women to assert their rights.

“Wait for no man,” Alcott advised her readers in 1877, when it was still improper for a woman to walk outside unescorted by a man. Young women should educate themselves through travel, she wrote. A lengthy European tour she had taken with a sister and a female friend “proved,” despite “prophecies to the contrary,” that women could travel “unprotected safely over land and sea ... experience two revolutions, an earthquake, an eclipse, and a flood” and yet encounter “no disappointment.” Assuming a motherly tone, Alcott wrote, “We respectfully advise all timid sisters now lingering doubtfully on shore, to strap up their bundles in light marching order, and push boldly off. They will need no protector but their own courage, no guide but their own good sense.... Bring home empty trunks, if you will, but heads full of new and larger ideas, hearts richer in the sympathy that makes the whole world kin, hands readier to help on the great work God gives humanity.”

Where did Alcott learn to think this way? Not from Dr. Johnson, who encouraged young men to explore the world, but from her mother, who was also her mentor and muse. Abigail May Alcott, born in 1800, was raised, to her regret, without formal schooling. Expected only to marry and raise a family, Abigail watched with longing as her brother received a “man’s education” to prepare for a career. “Stand up among your fellow men,” their father admonished her brother on his college graduation. “Improve your advantages. Go anywhere.”

Eighteen-year-old Abigail refused the hand of a man her father selected and then left home for a year to study with a friend of her brother’s. “I have undertaken” Latin, she informed her parents. Thrilled to translate a chapter of the Latin New Testament into English each Sunday, she confided, “If I should not succeed I should be mortified to have you know it. I wish my pride was subdued as regards this. I am not willing to be thought incapable of any thing.”

This determination would prove invaluable. At nearly 30 she proposed to the oddball reformer Bronson Alcott, with whom she had a difficult marriage and four daughters. Through three decades of poverty and intermittent homelessness, Abigail worked as a seamstress and social worker, encouraged her daughters’ education and careers, and dedicated herself to ending slavery and securing the vote for women.

A woman can accomplish as much as a man, Abigail May Alcott told her daughters so often they came to believe her. “Be something in yourself,” she advised every young woman she met. “Educate yourself up to your senses. I say to all the dear girls, keep up! Let the world feel that you are on its surface, alive!”

All her life Abigail May Alcott felt the absence of her father’s advice to a son: Stand up among your fellow men. Improve your advantages. Go anywhere.

With a fierce maternal love, she conveyed to her daughters a similar message, which Louisa relayed to us: Educate yourself up to your senses. Be something in yourself. Let the world know you are alive. Push boldly off. Wait for no man. Have heads full of new and larger ideas. And proceed to the great work God gives humanity.

Let us give thanks for our foremothers on Mother’s Day. Most are forgotten or hidden, and nearly all lacked political power. But we owe them gratitude for the sacrifices they made for their daughters, sacrifices that inspire us today.

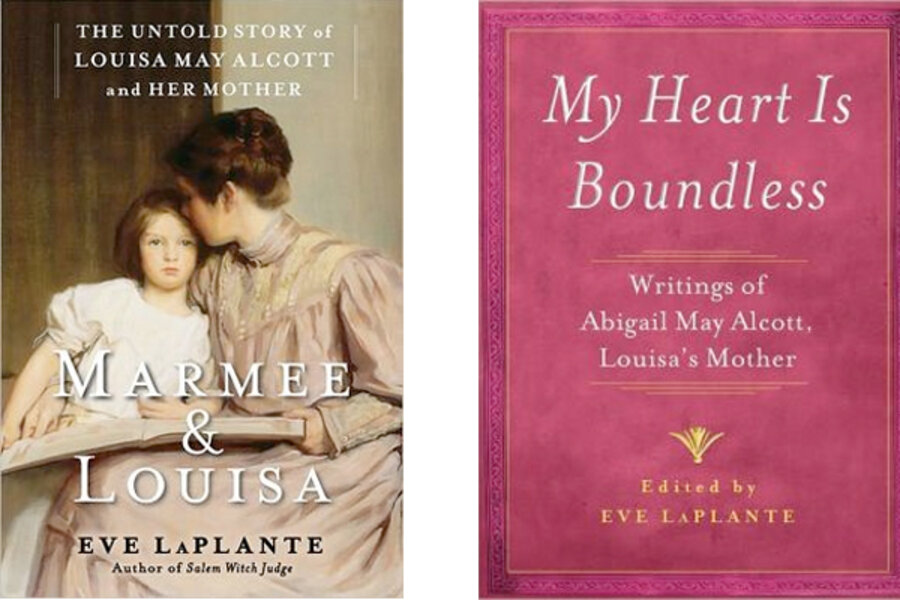

Eve LaPlante is the author, most recently, of "Marmee & Louisa: The Untold Story of Louisa May Alcott and Her Mother," and the editor of "My Heart is Boundless: Writings of Abigail May Alcott, Louisa's Mother. "