Ernest Hemingway’s Cuban archives now available in the US

Ernest Hemingway lived in Cuba for 21 years, from 1939 to 1960, where he wrote some of his most famous books. Recently, a set of 2,000 records that reveals a fuller view of his life in the country has been digitized and was released yesterday, on the 60th anniversary of the awarding of the 1953 Pulitzer Prize for “The Old Man and the Sea”. The materials had remained in a damp basement in Hemingway's house near Havana since the Nobel Prize-winner died in 1961.

Jenny Phillips, the granddaughter of Hemingway's editor, Maxwell Perkins, founded the Finca Vigia Foundation in 2004 to help preserve Hemingway’s literary records. The Boston-based organization, named after the author’s estate in Cuba, was able to get permission from the US Treasury and State departments to send conservators to Cuba to recover Hemingway’s belongings.

Phillips negotiated with both the Cuban and American government to gain access to the collection. “Scholars have been trying for years to see what’s there, and because of the political situation between the two countries, the Cubans held on very fast to what they had there," she said. "I think this is an extraordinary, one-of-a-kind collaboration between the two countries."

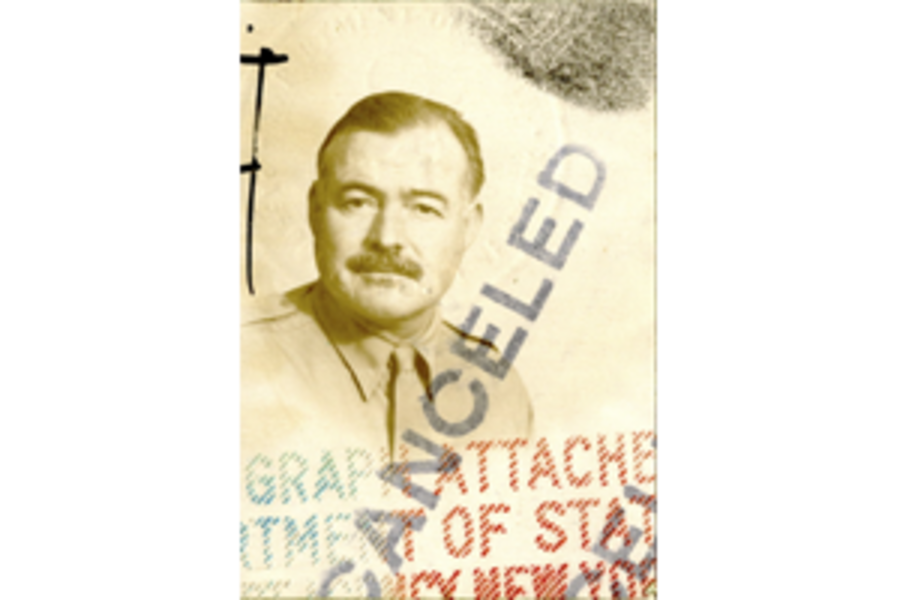

The records include copies of papers, groceries lists, bar bills, notebooks full of weather observations, and documents, such as files that reveal more about Hemingway’s role in World War II and his passports showing his travels.

The newly digitized files include some of Hemingway's personal correspondence, including a letter from American editor and literary critic Malcolm Cowley. "'The Old Man and the Sea' is pretty marvelous," Cowley wrote. "The old man is marvelous, the sea is, too, and so is the fish."

Poet and writer Archibald MacLeish wrote Hemingway a telegram in 1940, praising him for his work. "The word great had stopped meaning anything in this language until your book," MacLeish wrote. "You have given it all its meaning back. I'm proud to have shared any part of your sky."

In 2008, other documents from Hemingway’s estate had been digitized, uncovering fragments of manuscripts, including an alternate ending to "For Whom the Bell Tolls" and corrected proofs of "The Old Man and the Sea."

"This is the flotsam and jetsam of a writer's life — it's his life and his work," Phillips told the Associated Press. "All these bits and pieces get assembled in a big puzzle."

The newly recovered items will be housed at Boston's John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, which has a Hemingway collection of over 100,000 pages of writing and 10,000 photographs.