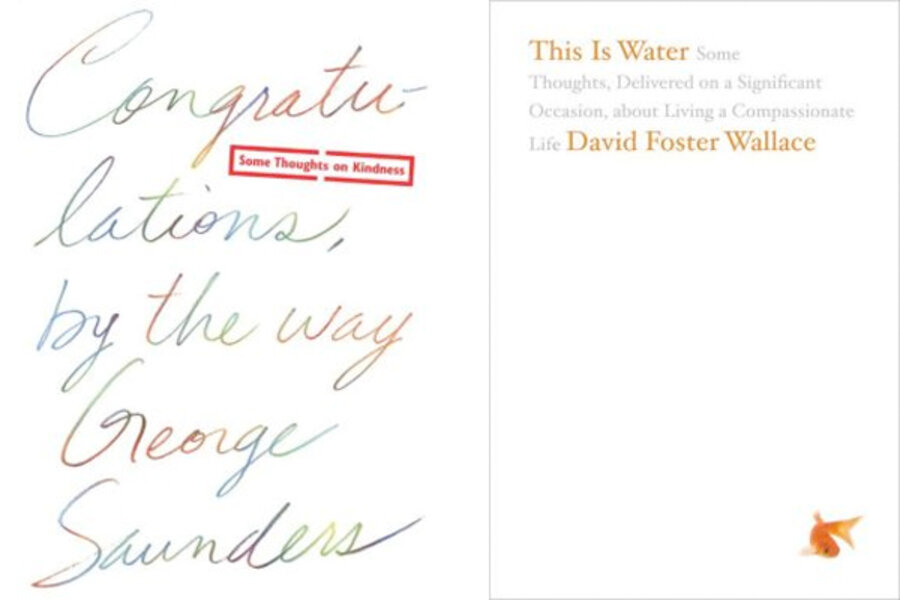

Graduation time: Skip 'Congratulations, by the way' by George Saunders and try David Foster Wallace instead

In many ways, I’m a quintessential Generation X-er. I was raised on "The Simpsons," came of age with grunge, and wore long skirts with combat boots in college. I graduated in what was called a recession, but in retrospect looks like the early tech boom.

I think we can all agree we are now really in a recession. Maybe that’s why I found "Congratulations, by the way: Some Thoughts on Kindness," the 2013 Syracuse commencement speech by George Saunders, profoundly irritating.

Saunders’ message is that kindness is what matters most. His rationale is that his major regrets involve failures of kindness. He illustrates this with an anecdote about not adequately defending a girl who was bullied in seventh grade.

"Congratulations" was a big hit when it was printed on the New York Times website, so I went there to see what I’d missed. What I gathered from the comments was that folks who liked it were not recent grads, but their parents.

“As I tell my kids, being nice is free,” wrote “I-See-Silver-Linings” of Silicon Valley.

But buried in the accolades, one reader asked a question that mirrored my own:

“Did David Foster Wallace not give this exact same speech at Kenyon many years ago?”

Um, yes. But Wallace gave it better.

First, Saunders ignores any of life’s material difficulties, which in this economy seems especially tone-deaf.

The students I teach are anxious about finding lucrative careers. Many are immigrants or the first in their families to attend college, which sensitizes them to the challenge of finding good work – and by “good,” I mean self-sustaining, not necessarily “meaningful.” My nephew is graduating from Swarthmore and despite his grades and school’s name-brand-recognition, he’s anxious, too.

Wallace’s address, "This is Water: Some Thoughts, Delivered on a Significant Occasion, about Living a Compassionate Life," was given in 2005, in pre-recession America. Even so, he refers to ten-hour workdays, squeezing in grocery runs and collapsing of exhaustion, only to begin all over the next day. He recognizes the grind of daily life most Americans face.

Even on kindness, Saunders seems out of touch. Bullying is a problem, true, even for adults, but such black-and-white situations come up far less frequently than do more subtle and morally ambiguous ones.

Also, Saunders never talks about the cost. What price might he have paid socially had he defended the geeky girl more fervently? What risks might an adult be taking who expresses an unpopular kindness in the workplace, not only socially, but professionally?

Saunders doesn’t tell us because he takes no risks himself in his writing. Rather than addressing particulars, he moves from his middle school metaphor to ask “why?”—as in, why are we self-centered?

His explanation reads like warmed-over Wallace:

“Each of us is born with a series of built-in confusions that are probably somehow Darwinian. These are: (1) we’re central to the universe (that is, our personal story is the main and most interesting story, the only story, really).”

Here’s the parallel passage from Wallace:

“Everything in my own immediate experience supports my deep belief that I am the absolute center of the universe.... We rarely think about this sort of natural, basic self-centeredness, because it’s so socially repulsive, but it’s pretty much the same for all of us, deep down. It is our default setting, hardwired into our boards at birth.”

I could quote other passages remarkably similar in tone and substance, but I’ll spare you.

Of course, a text ultimately reveals most about its author.

"Congratulations" is nostalgic, grandiose, and built on sweeping generalizations.

It’s kind of a bourgeois-white-male thing. Unlike Saunders, graduates who have little economic or family support may come to have more regrets about career or financial choices, just as certain women, who are often socialized into putting everyone but themselves first, may come to have regrets about not being more assertive.

Wallace is a privileged white guy, too. But the strength of his writing lies in its honesty – its addressing and even redeeming “large parts of adult American life that nobody talks about in commencement speeches” like traffic and grocery stores.

His call to decenter the self, to make empathetic leaps that transform teeth-grinding moments into sacred ones, is unsentimental yet moving.

It is “unimaginably hard to do this – to live consciously, adultly, day in and day out … to care about other people and to sacrifice for them, over and over, in myriad petty little unsexy ways.”

It was for him a matter of “life-or-death importance.” It’s worth a read.

Elizabeth Toohey, who teaches at Queensborough Community College in New York, is a frequent Monitor contributor.