F. Scott Fitzgerald in Hollywood: Author Stewart O'Nan explains what really happened

Loading...

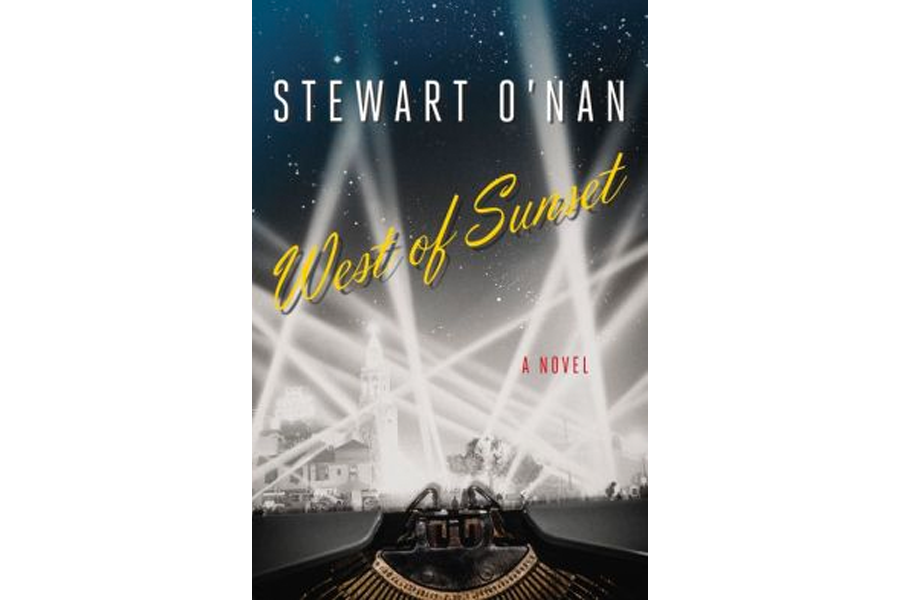

The heart-breaking begins early in the well-received new novel West of Sunset about the final years of author F. Scott Fitzgerald.

His high-flying literary career has evaporated, and his flapper wife Zelda, once the toast of the Roaring ’20s, is falling apart mentally and living in an institution. He takes her for a drive, and they talk about seeing their daughter. “I would like to see her,” Zelda says. “I wish I could tell you I’ll be good for her.”

He wants to kiss her but doesn’t. She has to go back to the home and get checked in by the nurse. He feels “like he was conspiring in his own defeat, a traitor to them both.”

This is the beginning, but far from the end. “West of Sunset,” a fascinating chronicle of Fitzgerald’s late-1930s escape to Hollywood prior to his death, isn’t a downer. In fact, author Stewart O’Nan, a prolific novelist, portrays a depressed, down-and-out genius who finds true happiness at the other edge of the country.

In an interview, O’Nan talks about Fitzgerald’s transformation – his newfound work ethic and the bonds he makes under the California sun. “He regained that love for the world, that romantic spirit that we think of as part of him,” O’Nan says, “that willingness, that openness, that receptiveness to life.”

Q: What attracted you to the story of F. Scott Fitzgerald in Los Angeles?

We’ll always be fascinated with Scott and Zelda’s fall from grace from the pinnacle of celebrity and fame. That attracts a lot of writers and readers. But I want to talk about that later story when he gets up off that mat and becomes himself again. I want Scott’s point of view, and you can only do that though fiction.

Q: What is happening to Fitzgerald when the book begins?

It’s 1937. His wife Zelda is in a private asylum in North Carolina, and he realizes that she is not getting better. His daughter is in Connecticut, and he’s deeply in debt to his agent. He has no other prospects, and he has no choice but to try screenwriting for the third time.

Q: I get the sense as the novel starts that things are happening to him, not the other way around. Is that a fair description?

He’s not in charge in this world. This is right after the time he described in “The Crack-Up.” He’s become this different person who really has no emotional resources he can give to other people. Then he goes to Hollywood and things change.

Q: What turns his life around?

The Algonquin Round Table had moved west, so he lands in a place where he’s surrounded by people who know and respect him. He has to get back on his feet, and he does, and he falls in love. He regains himself and his love of writing. Suddenly he’s back in love with the world.

Q: But he’s still married when he falls in love, and his mentally ill wife is still institutionalized. How does this conflict affect him?

He’s terribly guilty. He flies back east and visits Zelda and they go on therapeutic vacations, a week in Miami or Charleston with the ultimate goal of her going home to Montgomery, Alabama. But their romance is basically over at this time. He’s a great romantic, and it’s not the romance he needs in his life.

Q: His love interest is Sheilah Graham, a top gossip columnist. What is she like?

She’s smart and ambitious, beautiful and capable, and in a way she’s the New Woman, the way Zelda was the New Woman for 1917 and 1918 – a woman who flouts convention and has her own agenda.

Q: What should we know his work during this time, which isn’t that well-known?

Over the the three-and-a-half years he’s in Hollywood, he writes probably 400 beautiful pages of prose fiction and 8-10 screenplays and he doctors screenplays. He gets a lot done in that time, even while he’s struggling with his health and alcoholism.

The research for the book made me see how hard he worked. We see him as lazy and unproductive with this beautiful gift. But he works and works.

Q: Do you think Fitzgerald was happy in his final months?

He pulls it back together. When he’s sober, he’s a proper gentleman. Once he gets to Hollywood, he can recapture the person that he once was. But the bodily damage has already been done.

The terrible thing is that he dies when his work is better, he’s happier personally, he’s among very supportive friends, and the relationship with Zelda is stable.

Q: Did he redeem himself in the end?

No doubt about it. He redeemed himself, by not giving up and not quitting and doing really good work.

He regained that love for the world, that romantic spirit that we think of as part of him – that willingness, that openness, that receptiveness to life. And he understands what he’s going through, which makes it all the more poignant.

Randy Dotinga, a Monitor contributor, is president of the American Society of Journalists and Authors.