Dreams, divisions, and death: author Francisco Cantú shares what he saw at the Mexican border

Loading...

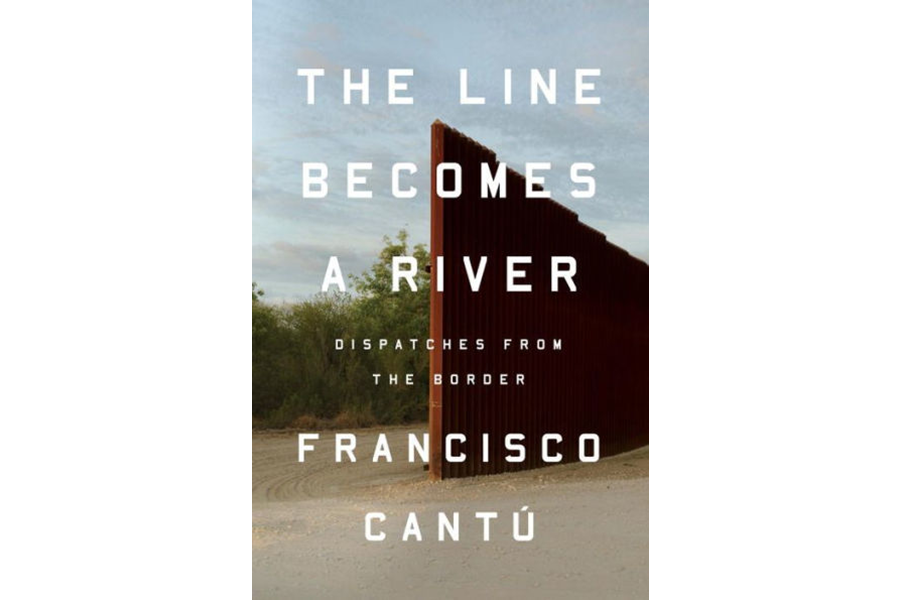

The Line Becomes a River: Dispatches from the Border, the extraordinary new book by young author Francisco Cantú, is peppered with tales of people making poor decisions.

Some of his fellow US Border Patrol agents are cruel, just like the "coyotes" who abandon the migrants they promise to shepherd into the US from Mexico. Many of the illegal crossers heedlessly gamble with their lives and those of their loved ones. The US government doesn't seem to flinch in the face of thousands of deaths in the Southwestern desert.

But Cantú, who joined the Border Patrol after college to better understand the border, isn't here to judge individuals. Instead, he watches, reports, and agonizes. The result is an intense and captivating memoir of dreams, divisions, and death at the border.

In an interview, Cantú talks about empathy for a would-be drug dealer, the horrific price of current border policies, and his hope for the future.

"There's a way of having these conversations about the border that rejects the simplified rhetoric we're being fed," he says, "a way that acknowledges it as hugely complex, as nuanced."

Q: When did you first start thinking about the border?

The border really entered my consciousness in a significant way was when I had my first job in high school as a bus boy in an Italian restaurant in Prescott, Ariz.

All the kitchen staff was from the Mexican state of Guanajuato. When I took my first trip to Mexico, I asked the dishwasher, "Is it hard to get to your village?" He put me in touch with his brother, who was getting married the same weekend that I would be there, and he invited me to his wedding.

All of a sudden, I was in this village thousands of miles from my hometown, and everybody there had some connection to the place where I grew up: They'd lived there or worked there or been deported from there.

I became conscious of the border as a place that could be very small. In that moment, distance felt very shrunken down.

Q: You don't tend to judge people in the book. Why not?

I write about this kid who was about 19 and had been left behind in the desert by his guide because he couldn't keep up.

He became lost in this terrible area that Border Patrol agents hated, an area of deep mesquite thickets where you can't even stand up, you have to crawl. He was just screaming, and someone heard him, went in, and found him.

My interaction was just to bring him water. He told me that he was sort of bewildered, that he was ready to die.

And then it was slowly dawning on him on the ride back that he'd be processed for deportation and thrown back to the place he risked his life to flee. He also said he had a connection in Portland and heard he could make all this money selling heroin there.

For most people, that's a drug dealer you kept out of the country. For me, that's a kid who almost died. To judge him in that moment when he's panicked and close to death – that's not my place.

Q: You seem hardest on yourself. How come?

After I'd extracted myself from the Border Patrol, I did a lot of soul-searching and grappling with the violent nature of the work I'd done and my culpability within a larger system. Part of that was looking at all the ways I lent parts of myself to support policies that feel violent or inhumane.

I'm concerned with how you can and can't extract yourself from an institution: Where does the institution end and the person begin?

Q: How should the border work?

I don't know. It's an insane thing, an imposed and an unnatural thing. I don't think there is some model of how a perfect border should work.

What I can say is that there are specific things that are happening that are wrong.

The biggest thing is this policy of enforcement through deterrence, enforcing the border in the heavily urban areas and forcing people to cross in the more remote, dangerous parts.

That policy has caused a constant parade of death. Hundreds of people are dying in the desert every year, and 6,000 or 7,000 people have died since the year 2000. It's becoming more deadly to cross, not less deadly.

That's unacceptable.

Q: What gives you hope?

Nothing is as powerful as an individual story, having someone in front of you saying, "I'm here to work. If you don't believe me, give me work to do right now. I'll take out the trash in the station while I wait, I'll sweep the floors."

l have hope that we can find new ways of having this conversation by talking to the people in our communities who are undocumented, listening to their stories, reading their accounts.

And I hope the book will compel people to think about moving beyond empathy and compassion to how these can be translated into action.