When US Congressmen turned to violence

Loading...

Slavery put sacred honor, individual manhood, and American freedoms on the line during the decades before the Civil War, spurring many of the men who ran the nation to fight each other with more than polite rhetoric.

US congressmen punched their fellow legislators, challenged each other to duels, and spilled blood in the halls of power. They viciously bullied and threatened each other too. And they did so to a stunning extent that hasn't been known until now.

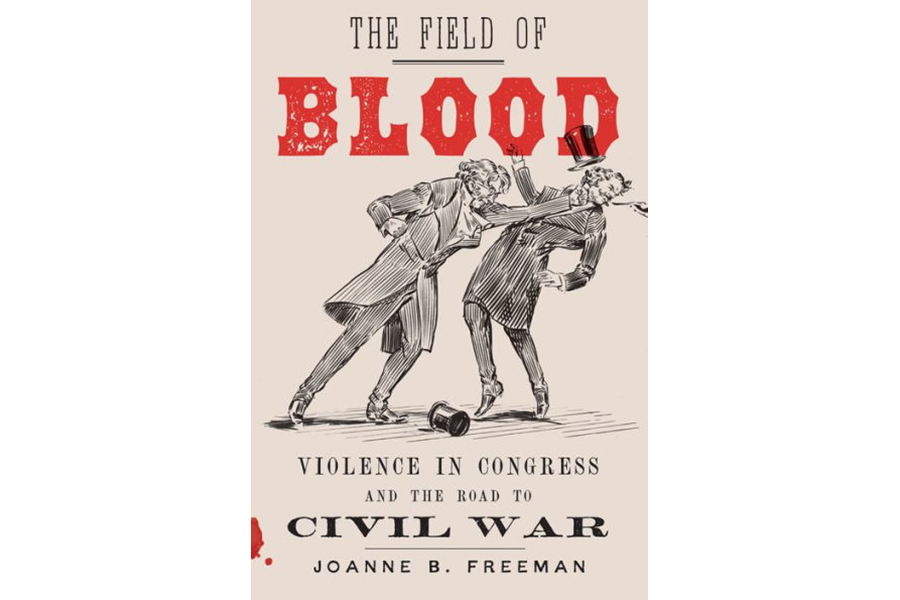

In her vivid and remarkable new book The Field of Blood: Violence in Congress and the Road to Civil War, Yale University historian Joanne B. Freeman puts dozens of forgotten episodes of political violence into stark context.

Its title notwithstanding, this isn't a grim slog through our unsavory past. Freeman's wry touch and appreciation for the absurdities of politics – and politicians – give the book a burst of energy and readability. Most vitally, the story she tells has heightened relevance in our own tumultuous era.

Here are excerpts from Freeman's conversation with Monitor contributor Randy Dotinga.

Q: What inspired you to write this book?

The short answer is: I found great evidence.

After completing my first book – a study of the national political culture of the 1790s – I decided to explore the political culture of the 1830s to see how it changed. I started by reading the papers of a congressman whose colleague was killed in a duel.

In his frequent letters to his wife, I kept finding violence. Congressmen threatening each other, slugging each other, or pushing up their sleeves to throw a punch. In three months of research in congressional papers, I never opened a collection without finding at least one violent threat or clash. Clearly, here was a story waiting to be told.

Q: What helped to spark this bloodshed?

Antebellum America was a violent place. There was the expulsion of Native Americans from their lands and sweeping massacres of their people. There were rampant mobs for a host of reasons: anti-abolitionism, nativism, racism. And of course, there was the institution of slavery itself.

Politics was also violent. There was hand-to-hand combat and rioting at polling places, and occasional "wrestling, knocking over chairs, desk, inkstands, men, and things generally" in state legislatures.

Even without the polarizing issue of slavery, there likely would have been some low-level violence in Congress.

Q: Why were Southerners especially brutal?

By definition, a slave regime was violent and imperiled. The chance of a slave revolt inspired a wary defensiveness on the part of slaveholders, making them prone to flaunt their power and quick to take violent action.

After the infamous caning of Massachusetts Senator Charles Sumner in 1856, one Southerner voiced that sentiment in a letter to a friend. Given the seriousness of Sumner's insults against slavery, Southerners, and the South, had he not been caned, "the impression would have been confirmed, that the fear of our slaves had made us such cowards that we could be kicked with impunity."

Q: What price did the nation pay for these battles of words and fists and worse?

Congressional threats and violence didn't cause the Civil War, but they paved the way. They schooled a watching nation in the look and feel of sectional combat, and inspired constituents to urge their congressmen to fight; some Northerners even sent their representatives weapons.

They eroded Congress's core practices of debate and compromise. They bred a growing distrust in the ability of national institutions to brook sectional divides. And ultimately, they led Northern and Southern congressmen – and Americans generally – to distrust each other.

Clearly, the consequences were severe.

Q: Are there people to admire in your book?

I came to admire John Quincy Adams's fight against slavery in Congress. Elected to the House after his presidency, he was a fighter of the first order, though not with his fists.

Elderly, a former president, and the son of a founder and former president, he couldn't be physically attacked. He used that fact to his advantage in his fight against slavery and for the right of petition, pushing boundaries and making demands. The same holds true for some of the Republicans pledged to fight the Slave Power. To at least some degree, I came to admire their commitment and their willingness to fight.

Q: What lessons does the story you tell hold for today?

It shows how the convergence of a bundle of problematic factors can lead to a national crisis. "The Field of Blood" is a story of extreme polarization in politics; fracturing national political parties; new technologies like the telegraph giving the press a new power; and Northern and Southern reporters and editors filling newspapers with conspiracy theories to promote their cause. As a result, Americans inside and outside of Congress grew to distrust each other, and eventually, to distrust the ability of national political institutions to resolve the nation's raging sectional conflict. It's not hard to see the many ways in which that story is being told again, in a different time with a different logic and different causes, but with some striking similarities nonetheless.