Western author Louis L'Amour's first novel? A seafaring tale

Loading...

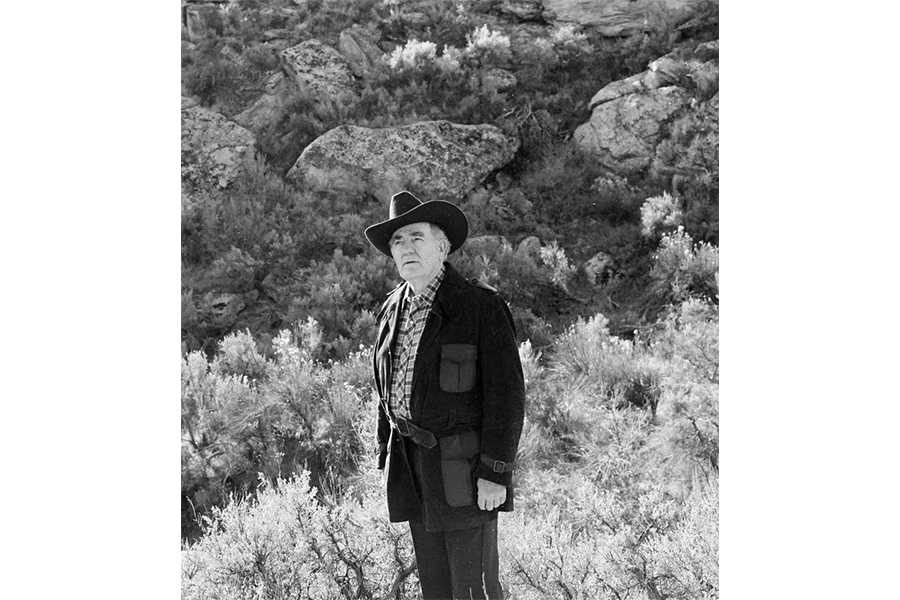

Louis L'Amour, one of the most popular authors in world history, created iconic stories about the American frontier in dozens of westerns. Fans snapped up hundreds of millions of copies of his tales about heroic cowboys, admirable Native Americans, and pioneer women.

L'Amour's own early life was as wild as the West. As a Washington Post writer reported in his 1988 obituary, "He was a longshoreman, lumberjack, elephant handler, cattle skinner and hay baler ... and was a seaman aboard an East African schooner." He was a boxer and an Army soldier, too, plus even more.

L'Amour never published his first novel, "No Traveller Returns," which draws upon on his early life at port and at sea. Now, the novel is being released for the first time with the help of his son, Beau L'Amour, as part of a series of "Lost Treasures." Random House is also re-releasing "Yondering," a collection of L'Amour short stories inspired by his youth.

In an interview, Beau L'Amour described "No Traveller Returns" is his father's "most personal book." He also talked about his dad's tough early life on the waterfront, his bid to write more than westerns, and his legacy today.

Q: How do these two books stand out among your father's work?

A: In his other work, he wrote a few stories that were literally directly from his life, and he wrote another few which were maybe one or two degrees off. Then he wrote a lot of things where aspects of his life served as background.

"No Traveller Returns" and "Yondering" really contain the most personal things about him. His experience on land and at sea directly contributed to them.

[Working on the books] absolutely brings me closer to him. It's really meaningful to work on something like this that is more personally drawn from his life.

Q: Why did he set the novel in San Pedro, the port of Los Angeles?

A: In his late teens, he hoboed his way out to San Pedro. He wanted to get on a ship. He'd been surviving off all kinds of very short-term work, and this was a long-term job that appealed to him.

When he got to San Pedro, he discovered that there were so many seaman out of work – "on the beach" – that it took a long time for him to get a bunk. He told me that when he signed up at the Marine Services Bureau, where you'd get a billet on a ship, there were something like 700 names ahead of him.

He lived hand-to-mouth as a homeless person, sleeping in lumber piles and abandoned houses and begging for food, doing odd jobs when he could find them.

Q: His first novels wasn't a western, and several of his last novels didn't quite fit the category, either. Did he try to break out of the genre?

A: He loved writing westerns, but he very much wanted to write other things. He struggled tremendously trying to get publishers to accept his other material.

A publisher wants to sell a writer in a certain way. And right when he started feeling fairly confident about writing other material, after he'd written 10 to 12 successful westerns, the paperback book business went through a change in 1958 to 1962.

Prior to then, they'd always racked their books by publisher. Afterward, books were racked by genre, and no publisher wanted to take a writer out of the section where the public knew where to find him. That made it harder to break out of your niche.

He wrote the "The Walking Drum," probably one of his more famous novels, in 1960. It's a 12th-century adventure story that takes place in Europe and the Middle East. He wasn't able to sell it until the mid-1980s.

Q: How did he manage to eventually expand beyond traditional westerns?

A: He decided to change the western genre once he finally realized he wasn't going to get himself out of westerns and still make money. He started pushing the envelope until he was able to write things that were different enough: Stories that took place earlier and earlier in the frontier period, stories that mostly took place in Europe, a Shakespearean-era adventure, and "weird west"/supernatural stories that veered into science fiction and fantasy.

By the end of his career, he sold his novels "The Walking Drum," "The Haunted Mesa" (science fiction that was slightly western-oriented), and "Last of the Breed," a Cold War thriller.

He was finally able to get what he wanted without staging a wholesale revolt. That brought him back to the beginning of his career at pulp magazines when he wrote everything, all kinds of genres.

Q: What is your father's legacy?

A: I would hope that his legacy is a lot of good entertainment. He taught himself to write directly from the unconscious, with very little planning, so his work has this incredible energy. You the reader are discovering the story as my dad discovered the story. You're kind of carried along. I liken it to surfing: My father is the wave, and you are the surfer.