G-20 leaders agree to next economic steps

| WASHINGTON

It was no Bretton Woods II. But the Washington economic summit may have made history by, in essence, expanding the world's financial board of directors – and starting a process that could lead to more coordinated global action on the current crisis in months to come.

Summit leaders agreed to hold a follow-up meeting on April 20. By then, the US will be led by a new Obama administration, which may be more inclined than its Bush predecessor to accept international financial regulatory reforms.

That doesn't mean that a President Obama will accept the sort of cross-border financial regulation that Europeans have long pushed for, say analysts. But it may mean that at the least he will accept a larger role for the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and other global institutions.

"You can expect that the [Obama] administration will listen and be more responsive precisely to where it is that America's actions fit into the larger global context," said Colin Bradford, a Brookings Institution expert on international economics, at a seminar on the Washington summit.

Bretton Woods was the seminal 1944 conference held at Bretton Woods, N.H., where 44 nations drew up the postwar global financial order. They created the IMF and the World Bank at that meeting, among other things.

The Nov. 14 and 15 Washington discussions were not designed to reach those heights. Instead, their purposes seemed as much political as technical, with leaders from Nicolas Sarkozy of France to China's President Hu Jintao talking about domestic financial rescue measures they have already taken.

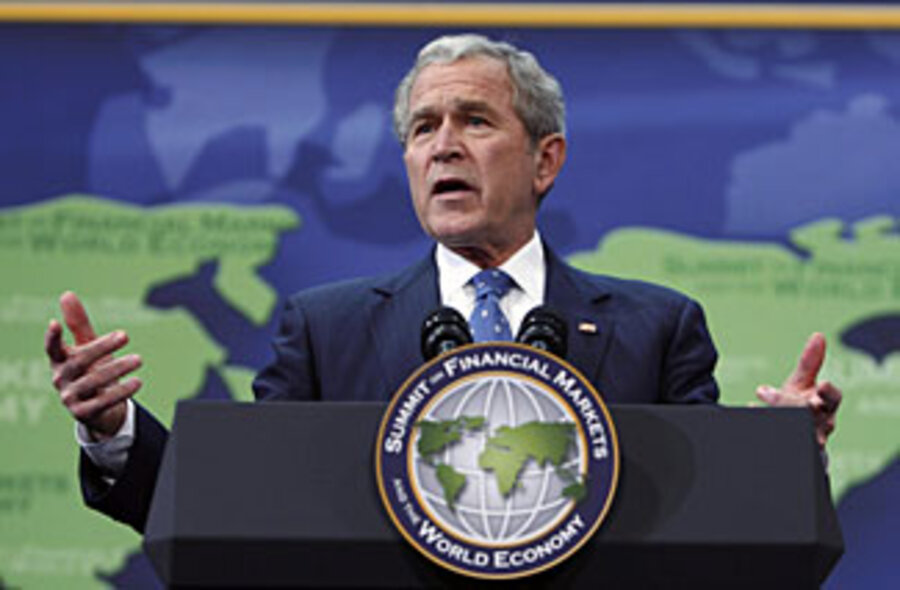

President Bush served as host and made a forceful appeal to world leaders that they not try to reinvent the free-market system.

"There was a common understanding that all of us should promote pro-growth economic policy," said Mr. Bush after the sessions. "There is more work to be done and there will be further meetings, sending a clear signal that a [single] meeting is not going to solve the world's problems."

In a postmeeting communiqué, leaders of the assembled group of G-20 nations said they agreed a broader policy response is needed to combat the current global economic crisis, based on "closer macroeconomic cooperation."

Listing a series of general principles, the leaders pledged to strengthen the transparency of their financial markets and their own regulatory regimes, among other things.

They also agreed to look at executive pay levels to see if those had contributed to the crisis, and to try to tighten regulations on credit default swaps, complex derivatives that may have helped credit problems cascade through the world financial system.

World Bank President Robert Zoellick said the summit was a positive start. He praised China's $580 billion stimulus package and called on other nations to initiate government spending initiatives of their own.

"What matters now are the follow-up actions," said Mr. Zoellick.

Zoelick's singling-out of China for praise in some ways was indicative of the importance of the meeting. It may have marked a passage of sorts, with the old G-7 major industrialized nations supplanted as a steering group by the larger G-20, which includes the G-7, members of the European Union, and major emerging economies such as China, India, Russia, and South Korea.

This is important because these countries have deserved a seat at the global economic table, said Eswar Prasad, a Brookings Institution senior fellow on international economics, at the Brookings seminar.

"The big issue is whether they [will] have the influence that goes with it, and I think that will require a much more substantive change ... in the way the major economies of the G-8 deal with these [emerging nation] economies," said Mr. Prasad.

The scheduled April meeting is likely to be a G-20 conference also. The old G-7 may now become something like a caucus within that larger group.

With this change the world may now confront a particular, important issue.

"That is how to integrate Asia into what has been a transatlantic-biased world of the IMF, the World Bank, and the G-7 ... summits," said Brookings' Mr. Bradford.

Given his preelection rhetoric, it may be likely that President-elect Obama will embrace the expansion of this exclusive world club. Mr. Obama himself did not attend the meeting, saying it would be inappropriate. Instead, he dispatched a team of emissaries, including former Secretary of State Madeleine Albright.

European nations have long been more comfortable with the idea of cross-border regulation than has the United States. Despite the replacement of a Republican administration with a Democratic one, this is unlikely to change, according to some experts.

"An Obama administration wouldn't be willing to accept a global regulator. That's a step too far," said Brad Setser, a fellow for geoeconomics at the Council on Foreign Relations, at a CFR seminar.

But Obama is likely to accept deeper regulatory reforms at the national level, said Mr. Setser. And his administration is likely to be more willing to join in some new coordinated global effort to use government stimulus efforts to try to limit the extent of the world's downturn.

Obama signaled as much in a radio address over the weekend.

"If Congress does not pass an immediate plan that gives the economy the boost it needs, I will make it my first order of business as president," he said.r Associated Press material was used in this report.