One town that can't wait for Chrysler to leave

| Newark, Del.

Even before the announcement Thursday that Chrysler would file for bankruptcy, this town's future was altered by the decline of America's No. 3 automaker. Last December, the final vehicle rolled off the assembly line at the sprawling Chrysler plant here.

But Newark is not looking back to the plant’s shutdown or the loss of 950 blue-collar jobs with good pay. Instead, city officials are eagerly anticipating the prospect of turning the assembly lines into, say, a high-tech park associated with the University of Delaware, which is literally across the street.

“This is an incredible opportunity,” says Vance Funk III, the mayor of Newark.

An increasing number of communities need to figure out what to do with empty factories and unionized workers accustomed to Detroit-sized wages and benefits. In response, 50 of them have formed the Mayors and Municipalities Automotive Coalition (MMAC) – a group that aims to get mothballed plants back into use.

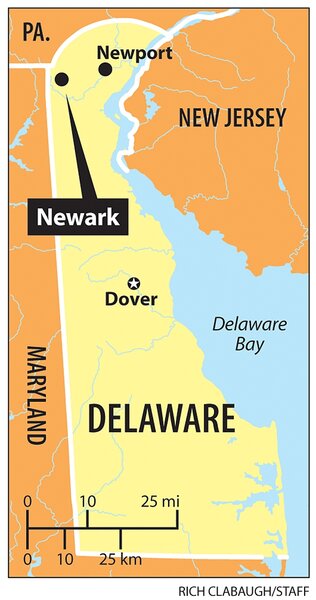

In Newark, that could mean a high-tech park. In nearby Newport, Del., home of a Pontiac plant expected to be closed, it could mean wooing an Asian carmaker. In Lansing, Mich., the mayor is hoping for federal help to clean up four shuttered GM plants that could be an environmental mess.

MMAC, which acts as a lobbying group, estimates that some 60 factories have already closed, and that General Motors may announce another dozen closures.

“Even with a successful restructuring, there will still be transitions and there will be closures,” says Matt Ward, policy director of the MMAC in Washington.

Many communities are hoping to get money from the president’s economic stimulus package to help either with economic development or worker retraining. The $787 billion stimulus package includes $1.5 billion for worker retraining. In the case of the Chrysler workers in Newark, the Delaware Department of Labor has already had many of the workers in for interviews. The goal is to assess the workers' job skills and determine their eligibility for retraining.

“We try to match their skills to careers,” says Bob Strong, deputy to the Labor Department secretary.

MMAC has a wide agenda to try to bring money to communities faced with plant shutdowns. It would like to see the Department of Energy move funds set aside for retooling of assembly plants that produce “green” cars. It wants public works and economic adjustment grants for closed plants. And it wants to greatly expand economic development money from the federal government – from $400 million in fiscal year 2009 to $3 billion in 2010.

Michael Spencer, Mayor of Newport, is simply hoping to convince GM to use the plant in his town for another car, perhaps a hybrid.

“I have heard it’s a first-rate facility; you want to keep that plant viable,” says Mr. Spencer. “If they can’t make a go of it, let’s sell it to someone who will, whether it’s a European manufacturer, an Asian company, or Ford.”

Spencer is hoping a regional approach will work since the plant affects businesses in Maryland, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania. “I know the governor and his staff are reaching out to other states,” he says.

Newark officials are reaching out to other states in a different manner. The Pentagon has already announced that by 2011 it will move most of the functions at its Fort Monmouth, New Jersey, base to Aberdeen Proving Ground in Maryland. Nine months ago, Mr. Funk, the Newark mayor, visited Monmouth County to try to lure businesses that might not want to follow the Army to Maryland. He says businesses there were quite interested in moving to Delaware because of the favorable tax climate.

“Based on what the university tells me, I would not be surprised if 50 percent to 75 percent of the site were taken by companies involved with the Army,” Funk says.

The selling points: easy rail transportation to Philadelphia and Washington, and the I-95 corridor is just a mile away. Officials are quick to promote the state’s pro-business, light taxes mentality. And if there is any need for federal funds: perhaps Vice President Joe Biden can call in some IOUs in Congress.

“They have to feed him a bone somewhere,” says Funk.

As is the case with any automobile facility, it would have to be cleaned up before it could be made into a science park. For years, the auto companies have sprayed paint and used heavy-duty chemicals and oils. In this respect, Chrysler's recent bankruptcy filing could complicate things. Chrysler is not likely to sell the site until it gets its financial house in order.

“We’re thinking nothing will happen at the site for the next 60 days" – the time the Obama administration expects the bankruptcy to last, says Funk. “But, time-wise it’s bad news.”

“The sooner the sale, the sooner it can get cleaned up, the buildings taken down, the property subdivided into parcels and made available to businesses that will be moving down to Aberdeen,” he adds. “We’re cutting it close now.”

Roy Lopata, director of planning for the city of Newark, says typically these projects get turned over only after the company cleans them up. “Chrysler told us it was their intent to clean the site,” says Mr. Lopata.

A Chrysler spokesman says the company is in negotiations with the university but the terms are confidential. “They are taking place and they are positive and we hope to able to secure the sale of the facility and put it to productive use,” says Mike Palese, a Chrysler spokesman.

In an e-mail, university official Scott Douglass says the school “remains interested” in the Chrysler property.

MMAC is hoping to get the Obama administration to agree to pay for some or most of the clean up with EPA Superfund money.

“We’re in serious discussions the Administration and Congress,” says Mr. Ward. “There is not any decision yet but they are thinking and working on it.”

The issue resonates with Virg Bernero, mayor of Lansing. The city has four GM plants that are now shuttered on a total of 450 acres in the Michigan captial. Three of of the factories have been razed and fenced off, but he says no environmental studies have been conducted.

“A lot of sites are kind of ‘don’t ask, don’t tell,’" he says. “If a company keeps them on their books they don’t have to do a lot of environmental testing.”

To Mr. Bernero, the solution is for the federal government to do the cleanup. “These are real toxic assets,” he says. “I know there is a big movement for making the polluter pay. It sounds great, but these sites are not at the top of the radar screen for companies fighting for survival, and we have to be realists now.”

Despite the difficult economy, Funk says he is optimistic the Chrysler property in Newark will become productive again. "If you display that enthusiasm, a lot of good things happen,” he says.