Indiana's Amish, laid off from RV factories, return to their plows

Loading...

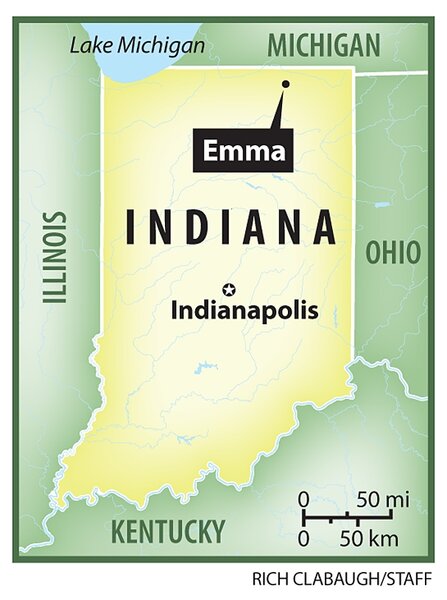

| Emma, Ind.

Emma, Ind.

For John Bontrager, the easy money has run out.

Mr. Bontrager, who is Amish, worked at a factory in nearby Middlebury, Ind., building FEMA trailers. He was not unusual; more than half the Amish men in northern Indiana had factory jobs. But when the RV industry collapsed last year, he and many others lost the work that supported their families and, over the years, enabled this Amish community, the third-largest in the United States, to grow and prosper.

While some are seeking jobs at local furniture shops or in construction out of state, Bontrager has decided to return to the traditional Amish livelihood: farming.

In January, he ordered a greenhouse – 30 by 96 feet and covered with two layers of plastic. Family and neighbors helped put it up. In late winter he planted it with 7,000 strawberry plants, stuck into plastic pots stacked six high. He expects his greenhouse berries to appear a month before local field strawberries and to taste sweeter than California imports.

“I think it’s going to be a real hit,” he says, the sun pouring down on rows of young plants and two small sons making mischief at his feet.

Amish men across northern Indiana are going back to farming, driven by necessity and also by a conviction that this is their proper work. Some are growing strawberries or tomatoes in hooped greenhouses that have sprung up in the countryside. Others are raising milk goats. Many are planting large truck gardens, putting in onions or potatoes or other vegetables to sell at a produce auction that the Amish have started in order to attract wholesale buyers.

The Amish, who for religious reasons shun modern conveniences such as cars and electricity, began here as farmers more than a century ago. But as their numbers increased – Amish couples often have 10 or more children – land prices soared and farms became increasingly unattainable.

Other Amish communities have met this challenge by starting home-based industries like furnituremaking and metal fabricating.

“In just about every settlement across the country, there’s been a shift away from farming toward small businesses,” says historian Steven Nolt at Goshen College, an expert on the Amish. In Indiana, however, the Amish found ready work in factories, making recreational vehicles.

The RV industry was a mixed blessing. Its high wages enabled many young families to buy a few acres and build a home. All around Emma, a rural crossroads in northeastern Indiana, stand gleaming new houses with white vinyl siding and, often, a matching barn.

But factory jobs also brought unease. Amish men rubbed shoulders with non-Amish who swore and engaged in other un-Amish behavior. The money encouraged habits the Amish frown upon, “spending it too much on themselves, going out to dinner too much, taking long trips,” says Otto Graber, a dairy farmer from nearby Shipshewana.

Worse, factory jobs kept fathers away from their children.

For these and other reasons, many Amish see a silver lining in the RV slump. “It’s probably good for the community,” says Kenneth Otto, who works only a few days a month at his factory job. “It was really good for too long. We just took it for granted,” he says, and “It got [us] away from farming.”

The idea of going back to farming has long tugged at the Amish. Nine years ago, a group of them began a produce auction near Emma, hoping to create a market. By last year the auction had blossomed to almost 100 growers. This year, organizers expect twice that many.

“Most ... say they’ve been dreaming about this ever since the produce auction started,” says LaVerne Miller, one of the founders. “But being they had a job, it was always ‘someday.’ ”

It won’t be easy. Mr. Miller and others have been holding meetings to instruct beginners in bee pollination, quality standards, and other issues. They say it’s unlikely that large numbers of Amish will suddenly make their living growing vegetables.

“It’s not all easy money,” says Perry Miller, LaVerne’s father, who grew up on a farm. “It takes hard work and determination. But it’s a pretty good thing if you put all your heart into it.”

Bontrager now spends a lot more time at home with his wife and 11 children. Like many US families, they have cut back. They’re baking their own bread, forgoing store-bought cereal, traveling less. “We’re just kind of struggling along,” he says.

He doesn’t know if the strawberries will turn out. He’d gladly work a few more years at the factory, to save up for more greenhouses. Yet he seems hopeful and confident, for now.

“In the Bible it says, ‘By the sweat of your brow you shall earn your bread,’ ” he says with conviction. “It’s more the easy-money way, going to the factory job.”