ECONOMIC SCENE: China's investments pose a new global challenge

Loading...

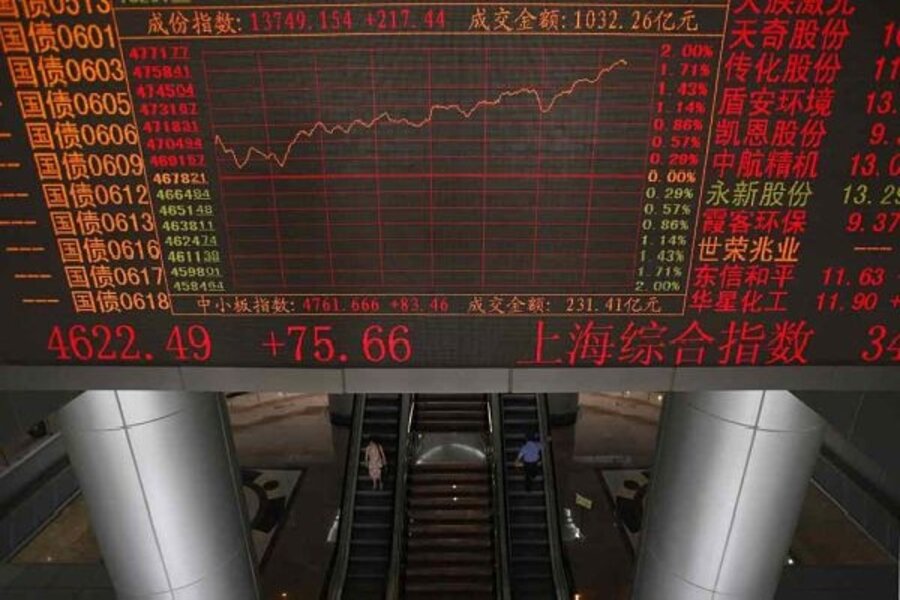

For a brief period in mid-July, China’s stock market edged out Japan’s as the world’s second-largest exchange. Then, Chinese stock prices tumbled some 20 percent in August, putting Japan back on top.

But watch out. Within the next 10 years, China’s stock exchange will zoom past not only Japan’s market but also the New York Stock Exchange to become the world’s largest equities market. That’s the prediction of James Trippon, editor and owner of China Stock Digest.

China will also become increasingly important in buying up companies and assets abroad, he adds.

One can almost hear the alarm bells that will go off in Tokyo, London, and New York. Headlines will warn of unsettling trends like "China Tightens Grip on Rare Minerals." But they’ll appear on front pages instead of the business section. Governments and economists alike will further ponder a new economic order.

Of course, the world has heard such predictions before. In 1967, Jean-Jacques Servan-Schreiber published “Le défi americain,” warning that United States multinationals were buying up much of the world’s productive assets. In the 1980s and ’90s, concern shifted to Japan as its companies became top global competitors and its investors bought famous US properties.

Such fears turned out to be overblown. Will China prove any different?

The case for China is well known. Its economy is on a tear, having grown 9 percent a year for three decades. Even the “great recession” managed only to slow down the growth in its gross domestic product – its output of goods and services – from 13 percent in 2007 to between 7.5 and 8.5 percent this year, calculates Nicholas Lardy, a China expert at the Peterson Institute for International Economics in Washington.

Furthermore, China still runs a huge trade surplus, even with a big drop in exports. And it has oodles of money – $2.1 trillion in its international reserves and a government-owned sovereign fund with $200 billion. Those assets can be used to buy up foreign assets, not to mention the unknown billions more Chinese corporations have available for foreign acquisitions.

That financial surplus prompts Peter Morici, a University of Maryland economist, to advocate taxing US dollar-yuan conversions to offset the conscious undervaluation of the yuan by Beijing. He calls that currency manipulation a “predatory” policy that gives Chinese exports a leg up in international trade.

But all is not rosy in China. Its Shanghai stock market acts at times more like a casino than a marketplace. Chinese investors, limited in their ability to invest in foreign stocks, pile in and out of their own market in a hurry, creating price volatility. Many stocks are priced extremely high. Also, China is “not a major player” in the area of international direct investment, says Mr. Lardy. “China is really just getting started in the last few years.” Last year, China’s foreign investment in plants and equipment came to only $50 billion and its stock of cross-border investments reached $170 billion.

A recent Peterson Institute study notes that China’s outbound investment in 2007 was comparable with Austria’s and the Netherlands’. US investment flows were 14 times larger.

True, Lenovo Group of Beijing did make a splash in 2005 with its purchase of IBM’s personal-computer division, becoming the world’s fourth-largest PC maker. Huawei Technologies, a telecommunications-equipment manufacturer, has launched joint ventures around the world.

Still, the US has about 30 times more foreign investment stock than China. Per capita, China’s stock of foreign investment amounted to $70, compared with $9,300 for Americans and $15,000 for Germans.

Could China fulfill its potential? Sure. But potential isn’t destiny.