Toyota recall: As firms go global, so do their glitches

You don't get much more "made in America" than the Chicago Telephone Supply Co. Founded in 1896 in the Windy City and later moved to Elkhart, Ind., it started corporate life by selling phones to rural Americans.

More than a century later, CTS, as it's now known, produces a wide range of made-to-order products for Hewlett-Packard, Cisco Systems, Raytheon, Ford – and Toyota.

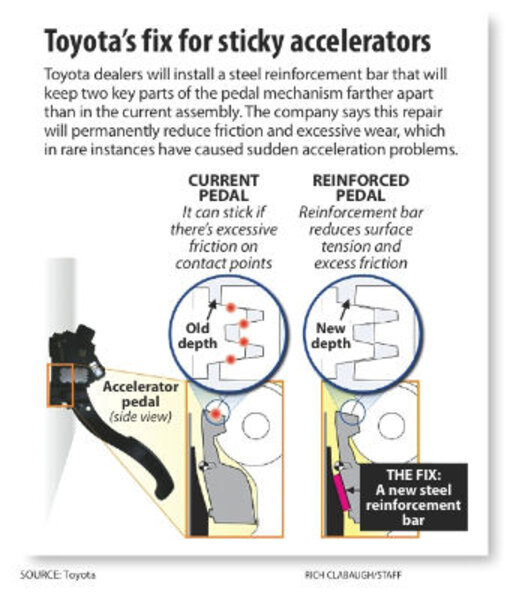

Last month, the Japanese automaker pointed to a faulty CTS accelerator mechanism as the reason for the recall and suspended production at its North American facilities for the week of Feb. 1. Toyota's problems have since mushroomed, with the federal government looking into broader quality problems. On Feb. 4, under pressure from the Japanese government, Toyota acknowledged a software glitch that caused braking problems in its made-in-Japan Prius hybrid.

Welcome to the dark side of globalization.

For decades, corporations have increasingly sourced parts and ingredients from around the world to produce its products. The effort has chopped prices and brought consumers better technology. But it can also blindside them if a shoddy part escapes detection and gets whisked around global distribution systems. Just ask anyone who bought a luxury US home with tainted Chinese drywall – or South Koreans put at risk by recalled peanut butter made in Blakely, Ga.

The issue is no longer Made in America versus Made in Japan or Germany. The challenge for consumers is that the product they buy is only as good as its weakest component, which can be made anywhere and everywhere. Globalization can make shoddy products harder to track. It can also make problems difficult to spot if corporations don't track trends globally.

"When someone publishes a list of affected products, can you figure out if you've got one in your pantry?" asks Elliott Grant, chief marketing officer at YottaMark, a Redwood City, Calif., firm specializing in product tracking. "There was a list of some 2,000 products listed in [the recent] peanut recall, so there is a need for someone to determine what is and what isn't affected."

US recall spreads abroad

When Toyota announced its US recall Jan. 21 for sticky accelerators, the action quickly spread around the globe. It recalled another 1.8 million vehicles in Europe, which used the same CTS part. Ford announced it was temporarily halting production of a Chinese commercial vehicle, which also used the CTS accelerator mechanism. Because Toyota produced a generation of the Pontiac Vibe in a former General Motors plant, 2 million Vibe owners will be receiving recall notices.

The fallout from the recall represents a huge loss of face for Toyota, which became the world's biggest automaker by stressing the importance of quality and safety.

Toyota has repeatedly referred to any sudden-acceleration problems as "rare" occurrences, a point disputed by Safety Research & Strategies, an advocacy group based in Rehoboth, Mass. Safety Research counts 2,262 unintended acceleration incidents from 1999 to 2010, leading to 341 injuries and 19 fatalities. Many of those occurred long before CTS became a Toyota supplier in 2005.

Despite these mounting reports and small electronics and other fixes dating back to 2002, Toyota did not acknowledge it had a widespread problem until last year, when it pointed to loose floor mats getting jammed under the accelerator. In November 2009, it issued a recall to replace the mats. The automaker says it first encountered a sticky-accelerator problem in March 2007 when owners of its Tundra truck began complaining that the accelerator was rough and slow to return to the idle position. Toyota traced that problem to a material in the pedal assembly, called PA46, that could absorb moisture and swell, according to documents Toyota filed with the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. The following year, Toyota switched to another material, called PPS, and concluded that the problem affected drivability, not safety.

Sticky accelerators popped up in Europe

In December 2008, Toyota began getting complaints from Aygo and Yaris drivers in Europe about sticky accelerators. This time it was the PPS material that seemed to be swelling, predominantly in right-hand-drive cars without air conditioning. Starting in August 2009, Toyota lengthened a part of the mechanism and changed the material again for all its European-made cars using that mechanism.

In October 2009, Toyota says it began getting reports of sticky accelerators in North America in pedal assemblies using PPS. Those reports led to January's recall of models using the CTS part.

Among the many questions now swirling around the company is why Toyota ignored customer complaints for so long before issuing recalls to address a safety issue. Also, if Toyota had a problem with sticky accelerators in Europe as early as December 2008, why did it wait until the following October before investigating the problem in the United States? And why fix the problem in new vehicles on the assembly line but not on cars already on the street? Toyota did not respond to requests for comment.

"Corporate ethics are to do the least you can so you're not spending time, money, and effort on vehicles you've already sold," says Byron Bloch, an independent automotive safety expert. "There has to be some combination of external pressures – like exposure in the media or public outrage [for a manufacturer to change practices]. If it's a dormant, quiet issue then the manufacturer can opt to deal with it on a one-by-one basis. They could blame it on bad gas, customer misuse, or claim it's so rare they've never heard about it before."

Sudden-acceleration problems are especially hard to track down. "The biggest challenge is that what consumers report is their perception. I've done it myself – I was driving and … accidentally, thinking I was putting my foot on the brake, put it on the gas pedal," says Bob Bennett, president of Lean Consulting Associates and a former group vice president for Toyota in the US. "People sometimes don't realize what they did."

When problems slip into a global system

Although many industries, including auto manu-facturers, have invested heavily in tracking their disparate parts, problems can be harder to dig out when they do slip into the production process.

"The quality assurance maybe isn't there upstream to look at this stuff – so when you have a problem, you have a real problem," says Dave Anderson, managing director of Supply Chain Ventures, a venture capital firm that invests in early-stage supply chain management companies. "That's inherent, that's a systematic problem, and one we haven't done a very good job addressing."

Component sharing can exacerbate the problem. The custom is common practice in the auto industry, where high levels of competition and cost-consciousness push manufacturers to install common components in multiple vehicles.

When a part is to be used in many different vehicles, you put "all your engineering behind one thing and make it work really well," says Jake Fisher, senior automotive engineer at Consumer Reports. "But on the flip side, if you have one problem, it's going to be everywhere."

There's also variation among suppliers. For example, Toyota says the version of the CTS accelerator mechanism made by its Denso supplier poses no problem.

"Even though you've got standardized parts, that doesn't mean they're manufactured in the same place with the same process. It may be the same specifications, it may be the same company, but manufactured in different locations," says Joel Sutherland, managing director of the Center for Value Chain Research at Lehigh University in Bethlehem, Pa., who worked for 11 years with major Toyota supplier Denso's US unit. "You may have different raw materials, different labor standards, different training, and all those have to be taken into comparison."

Fighting these problems takes a cultural shift more than a technological one, he adds. A company can't decide to adopt high-quality standards for just one project. "You have to make a commitment that is really long term," he says.

Sometimes, globalization can help companies find problems. With more people on different continents using a product, companies have a broader population to detect problems early on. In 2009, a driving fatality in South Africa spurred Honda to investigate its Fit models. It discovered that a master window switch was prone to overheating after being exposed to large amounts of liquid, posing a potential fire hazard.

After seven incidents and no injuries in the US, Honda recalled the cars a week after Toyota's recall.

• Monitor correspondent Husna Haq contributed to this story.