State budget woes: How much will they drag down US economy?

Loading...

| New York

States and cities collectively face the most precipitous decline in revenues on record, and the economy, while improving, does not appear to be picking up fast enough to prevent new layoffs of public employees and deep cuts in public services this year.

The budgetary downsizing is expected to act as a drag on overall economic growth, as the housing market has for the past three years. Just how heavy will this particular anchor be?

Economist Mark Zandi of Moody's Analytics in West Chester, Pa., estimates that state and local governments will lay off 150,000 more workers, after giving pink slips to 250,000 in 2010. Belt-tightening by state and local governments will shave 0.4 percentage points off America's gross domestic product this year, he predicts.

IN PICTURES: Pensions around the world

"It is a significant head wind, but it won't blow the recovery over," mainly because other head winds are subsiding, he says.

Like almost everyone else, states and cities have already endured two tough years. With the recession, their revenues fell, forcing pay cuts, layoffs, service reductions, and intense hunts for new revenue streams – sometimes all at the same time. What makes this year different is that states can't expect much help from Uncle Sam via a new stimulus package, meaning budget cuts are likely to be deeper than in the past couple of years.

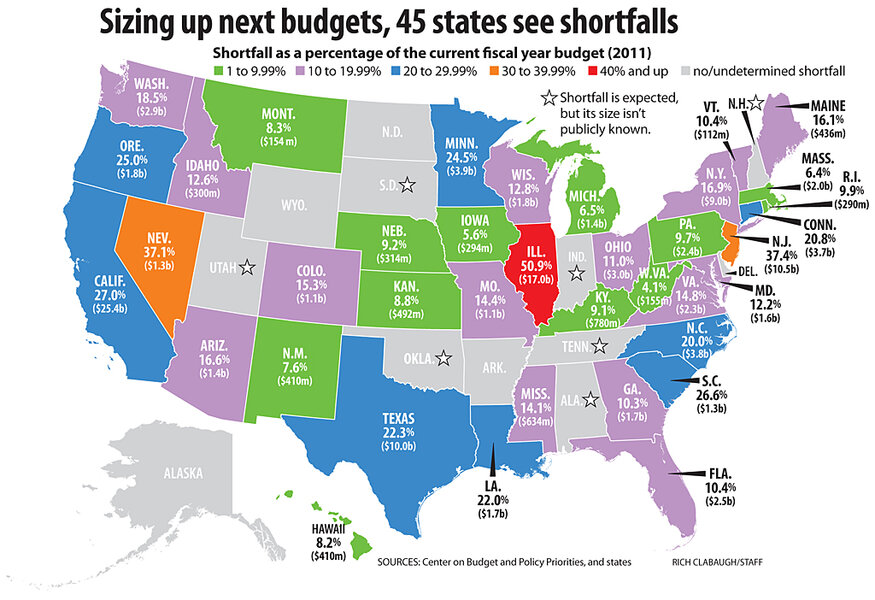

Forty-five states are expected to need to cut their next budgets, some a little and some drastically. Many states have difficult but manageable shortfalls, but 10 face budget gaps of 20 percent or more over this fiscal year's budget. Among them are some of the most populous states.

•In California, new Gov. Jerry Brown (D) and state lawmakers must find a way to bridge a projected $25.4 billion budget gap – more than double what the state spends on higher education each year.

•Illinois, with a projected budget gap of $17 billion, is so late paying its bills that it owes some vendors money from last August.

•New Jersey's projected $10.5 billion in red ink is equal to almost 10 years of tolls collected on the Turnpike and Garden State Parkway combined.

One prominent danger to the economy is that some state and local governments may decide they won't be able to pay the interest on their debt.

"It is hard to get to a scenario where the defaults undermine the financial markets, but it is a risk," says Mr. Zandi.

Some financial analysts, however, do see defaults ahead. One is Meredith Whitney, who correctly forecast the problems leading to the banking crisis in 2008. In December, on CBS's "60 Minutes," she predicted hundreds of billions of dollars in defaults.

In a November report, though, credit analyst Gabriel Petek of Standard & Poor's said broad defaults are unlikely. State and local revenues would have to drop by "substantially more than the average decline witnessed during the Great Depression before this priority protection [for bonds issued by state and local governments] would be breached," he said.

In fact, states' revenues are starting to rise again, reflecting the improving economy. In the third quarter of 2010, 42 states took in more from personal income taxes and sales taxes than during same period in 2009, according to a recent report by the Rockefeller Institute of Government, part of the State University at Albany.

"That's good news," says Don Boyd, a senior fellow at the institute. "But it is still below the levels needed to finance the spending commitments the states have."

That's the rub for public employees like Karen Flynn in Lincoln, Calif. She lost her job as part of Lincoln's need to reduce a $1.7 million deficit. She now lives with a friend to stretch her $1,700-a-month unemployment benefit, and keeps an eagle eye on every penny she spends, which does not help area retailers. Her Christmas spending last month: a $2 coloring book for her granddaughter and $20 for her grandson. "I've had much more lavish Christmases in the past," she says.

In Vineland, N.J., Joe Sangataldo, a jobs counselor laid off by the Garden State in October, has also pared back. He used to vacation in New Orleans. Now he plans to hop on a Megabus, which for $1 will take him to the Pittsburgh Convention Center. He'll spend the day there and then return for another dollar.

"I call it a budget vacation," says Mr. Sangataldo, adding that he learned how to scrimp from the people who have attended his job-counseling sessions.

The states' combined shortfall will total $140 billion for the 2012 budget year, which begins in June for most, according to the Center for Budget and Policy Priorities (CBPP), That mainly reflects lower sales- and income-tax collections.

"Usually, when a recession ends, it takes two to three years for state revenues to get back," says Jon Shure, deputy director of the State Fiscal Project at CBPP.

To avoid losing even more revenue, California's Governor Brown is proposing to retain a previous "temporary" tax increase that would have expired. In Illinois, the legislature approved a major increase in state and corporate income taxes. In some states, such tax hikes might in part offset the impact of the Obama-GOP deal to keep national tax rates from rising.

"I'm not sure if it would entirely wipe out the [tax] savings for some individuals, but it would be a dent," says Pete Sepp of the National Taxpayers Union, in Alexandria, Va.

The recent recession, however, is not solely to blame for the economic straits of states and localities. Many made spending commitments using unrealistic budget assumptions, says Mr. Boyd at the Rockefeller Institute. For instance, some states assumed that a big jump in revenues from capital gains taxes was the new normal – and raised their spending accordingly. "Capital gains have since fallen more than 70 percent from 2007 levels," he says. "The point is, you can't act as if that ephemeral income is there to support spending."

States are committed, moreover, to some spending programs that are growing faster than revenues. In Illinois, for one, the cost of Medicaid, a federal-state program to provide health care for the poor, has grown 6.9 percent a year over the past decade.

Many states also face a rising demand on their resources to fund pensions for their employees. "Most [pension commitments] are underfunded," says Boyd. "Unless they make drastic changes in the way they fund their pensions, some places are on a path to run out of money in seven to 10 years. Many will have to raise contributions and crowd out other parts of the budget."

Illinois is a poster child for how bad things can get. Its general fund has run a deficit for eight of the past 10 years, according to Standard & Poor's, the debt rating service. The state has survived mainly by issuing short-term debt and delaying payments to vendors, local governments, and higher education institutions.