Eat Peeps? Nah. Decorate!

This Sunday, upwards of $2 billion in Easter candy will be artfully arranged into colorful baskets across the United States. The usual suspects will all be present: Chocolate bunnies, jelly beans, Cadbury Crème Eggs, and Peeps.

Those celebrating Easter are set to spend $145.28 per person on the holiday, up from $131.04 last year, according to the National Retail Federation. Some 89 percent will buy candy, spending an average of $20.35. The top nonchocolate brand name seller (and the cutest candy in the bunch) will be Peeps, the unmistakable (and never imitated) marshmallow treats in the shape of chicks, bunnies, and a bevy of non-Easter characters. An estimated 800 million Peeps will be manufactured for the Easter season, according to the Peeps' parent company, Just Born, based in Bethlehem, Pa.

Unlike most other Easter treats, upwards of 400 million those Peeps won’t be for eating.

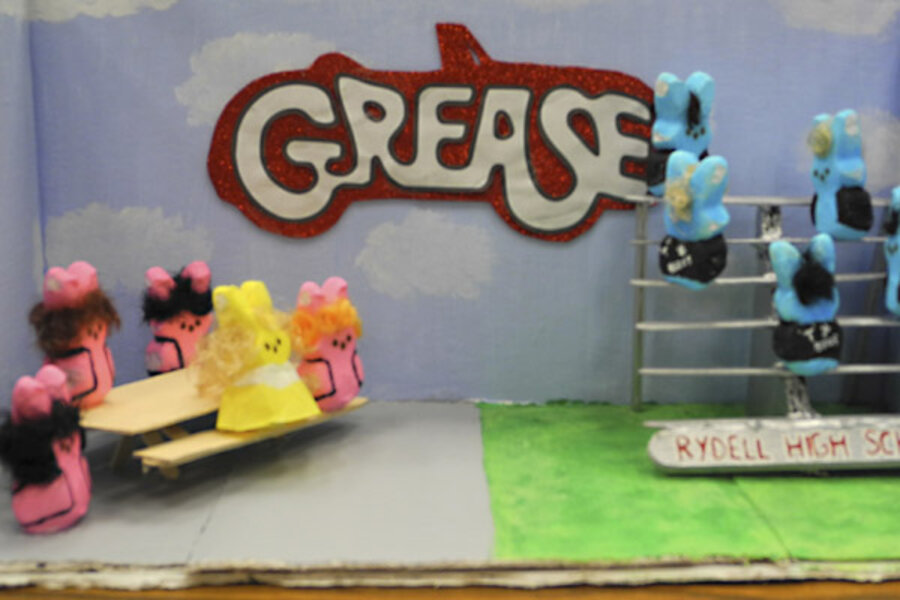

In the past decade, Peeps have become one of the rare treats known more, perhaps, for their decorative and artistic potential than for their taste. Around Easte, Peeps diorama contests are a common sight in newspapers and magazines. For the uninitiated, Peeps diorama contests are exactly what they sound like: Contestants create elaborate scenes incorporating the marshmallow candies, occasionally recreating current events and almost always incorporating groan-inducing puns.

This year’s winner for the Washington Post’s contest, one of the nation’s largest, was “Occupeep DC,” in which multicolored marshmallow bunny Peeps protest in an intricate replication of McPherson Square in Washington, D.C. The bunnies hold signs that read “Power to the Peeple” and “We are the 99 percent.”

The first Peep diorama contest was held in 2004 at the St. Paul Pioneer Press, in St. Paul, Minn. This year, at least 60 such competitions are being held nationwide, according to Just Born spokeswoman Ellie Deardorf.

“While the idea came from the Pioneer Press, we at Just Born had noticed an increasing trend among our fans to create with Peeps,” she writes via e-mail. “So we immediately reached out to the Pioneer Press and the Washington Post to offer prize packages.”

The company fronts the prize money and swag for 23 such contests, in all. That looks like smart marketing strategy because Peeps have, um, a potential flaw. While no one but the most curmudgeonly of souls would have anything negative to say about brightly colored marshmallows reenacting the Chilean mining rescue, or the Royal Wedding, the same cannot be said for the taste of Peeps themselves.

One informal poll in a certain Boston office unearthed not a single person who would actually admit to eating Peeps, much less liking them.

By company estimates, over one fifth of all Peep purchases are not for eating. That means in a given year, 400 million Peeps are used for art projects, decorating, and crafting.

What makes Peeps so ripe for artistic expression compared with other treats? For one, they’re sturdy, especially when stale. In a 1999 study at Emory University, scientists performed a batch of tortuous experiments on Peeps and found them to be surprisingly indestructible: The candies were burned with cigarette smoke, thrown in boiling water and liquid nitrogen, and doused with sulfuric acid. But the Peeps came out unscathed.

And it may be the Peeps’ unfazed response toward such torments that incite people’s fascination with finding new and creative ways to mistreat them. A popular one, “Peep jousting,” involves placing two Peeps in the microwave, facing each other, with toothpick inserted into each. Turning on the microwave makes the Peeps expand and the toothpicks flail wildly about, and the Peep that gets big enough to engulf the other is the winner.

At the previously mentioned Boston office, one person’s Peep recollection was intentionally running one over with his car.

Yet through it all, Peeps maintain their bright color, inscrutable expressions, and strong sales.