Student loan interest rate doubles. Government could pay more, too.

Loading...

Millions of college students woke up Monday to a new reality: The interest rate on their new subsidized Stafford loans – the most popular federal student loan program – doubled overnight.

The 6.8 percent interest rate will not only add to the financial burden of the 7 million or so students expected to take out Stafford loans for the coming school year – it could cost the federal government, too.

While the Congressional Budget Office estimates that federal student loan programs will generate $160 billion in profit in the next eight years, the research arm of banking giant Barclays says the Stafford program could add more than $100 billion to the deficit during that period.

The costs would come in two ways – and offset any gain the government would see in increased interest payments. (The higher interest rate only affects new Stafford loans made after July 1; current loans are not affected.) First, under the rules of the loan program, the new interest payments would be so high that some low-income borrowers would have their loans discharged altogether after making a certain number of payments.

“The way the program is currently constructed, the number of people who qualify for loan forgiveness is large relative to the number the government assumes will use the program,” Cooper Howes, a Barclays analyst, said in a phone interview. “Even for those who have modest incomes, if they have large enough loans, they have large amounts forgiven."

Second, a far greater proportion of students than anticipated could have their monthly loan repayments capped, dramatically slowing how quickly the government recoups student loan payments. The Department of Education estimates the provision will affect 6 percent of borrowers. Barclays says it will affect well over half of all new borrowers.

The rise in interest rates came because Congress failed to reach a compromise last week for the student-loan program.

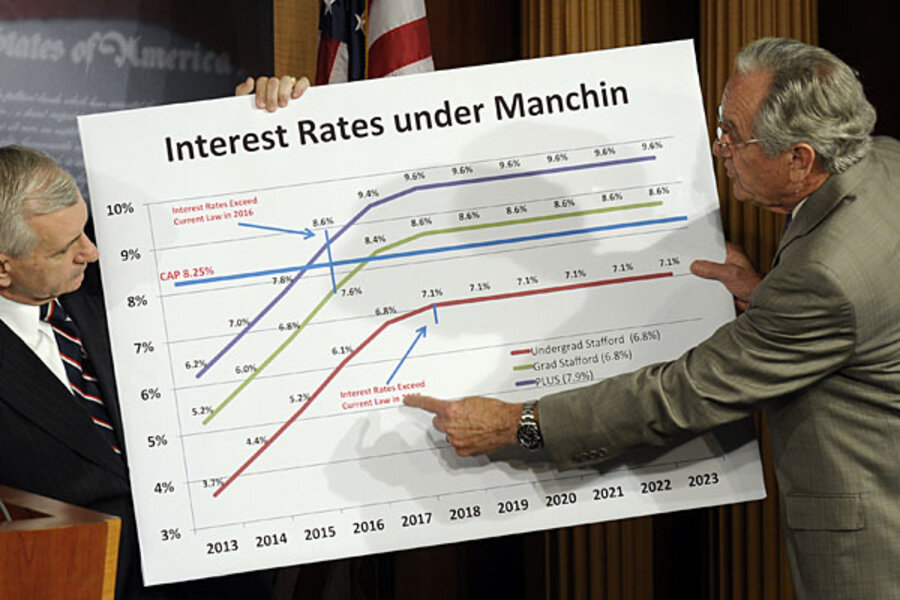

Annual congressional debates over student loan programs' sustainability have driven lawmakers like Sen. Joe Manchin (D) of West Virginia to fight for a bipartisan proposal to link interest rates on new loans to financial markets, rather than keep the old fixed rate of 3.4 percent. Under Senator Manchin’s plan, which closely mirrors ideas proposed by both President Obama and the GOP-controlled House, undergraduate borrowers would pay 3.6 percent interest rates on loans taken out this fall.

Mr. Howes says he believes any proposal to make interest rates market-based, whether it be Manchin’s or an alternative plan passed in the House, would be a “major step in the right direction.”

“Part of the reason why market-based rates are considered budget-neutral is because when interest rates rise, the rates that students will pay will also rise,” Howes says. With the current income-based repayment program, however, higher rates could result in larger loan balances being forgiven.

But Democrats and student advocates have quickly fired back at the Manchin plan’s supporters. They argue that the plan’s premise of tying interest rates to the 10-year Treasury note would allow interest rates to soar without limit.

“Any proposal that lacks a cap is a nonstarter and indicates that its proponents are putting their ideology above students and their families,” Allison Preiss, a spokeswoman for the Democratic-led Senate Health, Education, Labor and Pensions Committee, told the AP.

Believing none of the proposals to tie interest rates to the market will survive a vote, Sen. Tom Harkin (D-Iowa) pushed Congress to simply restore the 3.4 percent interest rates after its recess.

“Let’s put this off for a year,” Harkin told reporters Thursday.

The move to delay changing the student loan program may have broader ramifications, however.

Surpassing the $1 trillion mark and encompassing a record number of borrowers, outstanding student debt has been described as having "parallels to the housing crisis" by the Federal Advisory Council, which advises the Federal Reserve’s Board of Governors.

Barclays, however, believes that student debt poses the greatest danger to the government, not the economy as a whole.

For one, evidence suggests that college degrees generally remain a worthwhile investment, Mr. Howes says. Even though increasing student debt can hamper borrowers’ ability to make large purchases, “these effects are hard to isolate and will not necessarily prove to be a major macroeconomic headwind,” he added.

“Ultimately, the question is: Are fixed interest rates the right way to do it? I think the data we have suggest this could be a big problem, and we should look into it more,” Mr. Howes says.