The many rewards, and the hidden risks, of high-frequency trading

| New York

Ever since traders first swapped stocks under the buttonwood tree on Wall Street, speculators have worried that their competitors may have an unfair edge – a secret source of information or a manipulative market-moving deal that would make the game a rigged affair, favoring a powerful, in-the-know few.

Today, this anxiety has re-erupted into an intra-Wall Street donnybrook over what is known as "high-frequency trading." It's a dizzying Digital Age landscape of algorithmic robot traders that can analyze global markets, outgun slower opponents, and make their own decisions to buy and sell thousands of securities in less time than it takes to click a mouse.

In a culture of skyscraper-sized egos and "Hunger Games"-like competition, some of those outgunned have been crying foul. Such old-guard Wall Street analysts, feeling victimized by this brave new world of predatory "algobots," have been lining up against the relatively new breed of number-crunching "quants" who have been designing them. These analysts are more likely to have degrees in quantitative physics or mathematics than in business or finance.

True, anxieties about high-frequency trading have been simmering for years on Wall Street. But for the past month, the debate over it has become explosive, with nearly everyone in finance putting in their own US$0.02 about this often-bewildering technique, which makes up about half the volume of stock market trades.

The debate comes against the backdrop of a deeper cultural unease about the extent and power of "big data" processing, following the startling revelations last year about the extent of surveillance by the National Security Agency.

Call it the Edward Snowden effect, perhaps.

As algorithms are evolving within the rough-and-ready landscapes of global capitalism, their market-moving decisions can potentially affect the lives of millions.

"We're moving toward a world where we're starting to see different types of strategies, where the algorithm may even learn over time – a genetic algorithm or some form of machine learning," says John Bates, chief technology officer for the Intelligent Business Operations and Big Data division of Software AG, headquartered in Reston, Va. "So yes, it's about the algorithm being autonomous and making its own decisions."

How high-frequency trading works

With the advent of high-frequency trading in the US securities exchanges, the quants have, in effect, brought to the markets a new horizon of time and space, difficult for the human mind to comprehend.

In today's electronic markets, a second is the new day, and every millisecond counts.

While each high-frequency transaction yields only a fraction of a penny of profit per share, computers on digital steroids can process hundreds of thousands of these trades per day. The computers send out powerful algobot programs to find and exploit minuscule market spreads that exist only in the jiffy of milliseconds. These automated traders are monitoring their competition's moves and springing into action before the others can respond – along the way, collecting traditional but tiny transaction fees.

Though the classic American image of a trader flailing his arms with a fistful of orders in the pit of the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) has gone the way of the typewriter, proponents argue that the new big data era has not changed the fundamental system: It's only made it better and more efficient.

"We've just been transitioning, and the computers won," says Charles Jones, director of the Program for Financial Studies at Columbia University in Manhattan and an expert in high-frequency trading. "What I think is that a lot of the world changed pretty rapidly as we began to computerize, and a lot of the old winners suddenly became losers."

Opponents of the practice have been rankled when, as a trader tries to purchase a block of securities, a faster-moving algobot can "see" him or her attempt to make the trade, swoop in, and buy it first, before offering it back to the original trader at a slightly higher price.

This is similar to the illegal practice called "front-running," in which a company uses proprietary information – or insider information – to purchase a block of securities.

But in the digital space of network wires, such information is not considered proprietary but rather public. Thus any virtual trader with the right equipment can "see" orders as they're sent – and if the trader happens to be faster, that individual can use the info to his or her advantage.

"People always worry that someone else might be doing a little better than you are in investing," Mr. Jones continues. "Everybody's worried about being taken advantage of in some way, shape, or form. This has been true since the dawn of time on Wall Street, where people are inherently suspicious of everybody else who's participating."

Regulators grow wary

Right now, regulators and law enforcement officials are taking another look at the methods of high-frequency trading and its effects on the market. In February, the chair of the Securities and Exchange Commission, Mary Jo White, announced that the federal agency is stepping up its scrutiny of the practice.

New York Attorney General Eric Schneiderman, as well as the Federal Bureau of Investigation, is also investigating Wall Street's high-tech wizardry, which Mr. Schneiderman has labeled "Insider Trading 2.0."

And in April, the European Union passed much stricter regulations on the practice.

While high-frequency trading "might bring some benefits, we need to make sure that it doesn't cause instability, and isn't a source of market abuse, " EU financial services chief Michel Barnier told Bloomberg in an e-mail. "That's what these rules set out to achieve."

It was also in April that the issue burst back into public view with the splash of the book "Flash Boys," the latest exposé of ostensible Wall Street chicanery by storyteller extraordinaire Michael Lewis. The bestselling author caused a furor in March when he echoed the simple leitmotif of a number of Wall Street traders, declaring on the television news program "60 Minutes" that "the market is rigged."

But there's been something curious about the virulence of this Wall Street tussle. As critics have been quick to point out, Mr. Lewis's book really reported nothing new.

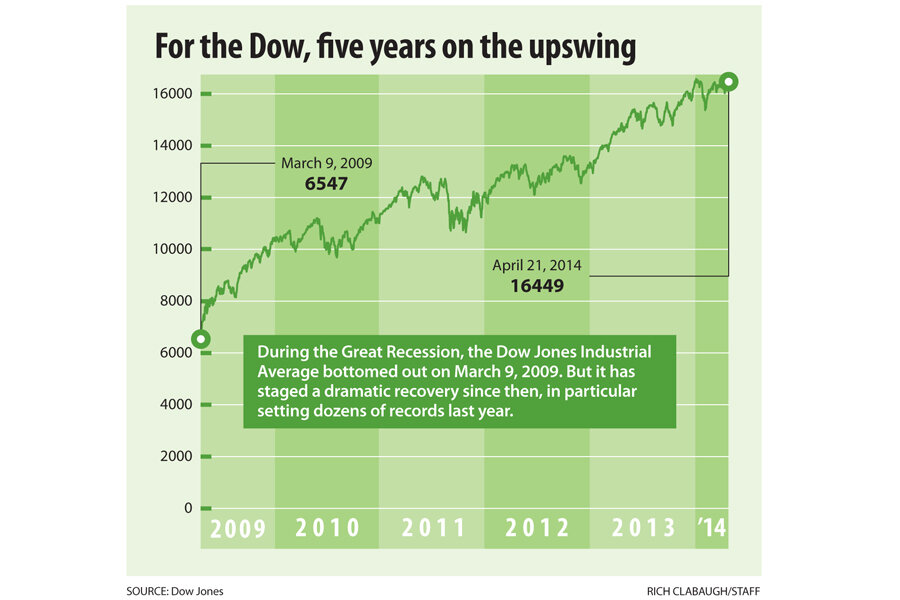

For one thing, the success of high-frequency trading has hardly happened in a vacuum. The Federal Reserve has been propping up the markets with hundreds of billions of dollars in free stimulus cash for years. Last year, the markets responded with record results, sending corporate profits soaring and making big banks some of the most powerful institutions in the world.

At the same time, Main Street's recovery from the Great Recession has been tepid at best, and so far not much of the jaw-dropping success of the markets has trickled down to stimulate employment and production.

So why would some on Wall Street want to fiddle with what appears to be one of the slickest moneymaking machines in history?

"I think to figure out why we're having this Michael Lewis moment now, you can't just reduce it to his PR team or to the quality of his writing," says Evan Selinger, a fellow at the Institute for Ethics and Emerging Technologies and a professor of philosophy at the Rochester Institute of Technology in Rochester, N.Y. "I think there's something going on in the zeitgeist.... There's something broader going on."

Enter the debates about the security benefits versus privacy costs of the NSA's domestic surveillance, or even the laser-accurate consumer profiles gleaned by companies like Google and Facebook. Now, even some of the players on Wall Street worry that an elite technorati, operating in a system only they can fully grasp, can mine far-reaching caches of megadata, allowing them to game the system and extract risk-free profits at other players' expense.

Federal regulators themselves, among others, acknowledge they've been slow to understand exactly what has been happening in the strange time and space horizons of the current market system. They, too, have lacked the technology to peek into the "matrix" to observe what the algobots are doing.

"They're way behind the curve from a technical standpoint," says Larry Doyle, a former trader in mortgage-backed securities and author of "In Bed With Wall Street: The Conspiracy Crippling Our Global Economy," a scathing insider critique of the Wall Street system. "Wall Street is light-years ahead, and that's a problem."

A 'tax' on your transactions?

Critics of the practice say it's not simply a matter of sour financial grapes. Regulatory changes in 2005 tweaked the rules of the wires for the US electronic market infrastructure: Price quotes for securities switched from fractions, in which 1/16 was the smallest unit, to decimal places, putting 100 pennies into play for every sale. (For securities under a dollar, decimals extend four places.) And public exchanges like the NYSE morphed from nonprofit cooperatives to for-profit publicly traded companies. The system was virtually designed for algorithms – of which high-frequency trading strategies are only a part.

"That's the real problem," says Aaron Izenstark, managing director and chief investment officer of IRON Financial in Northbrook, Ill., near Chicago. "So if there's a situation where computers are able to monitor what you are doing, legally, and because the regulations were moved that way in order for exchanges or electronic communication networks to sell your information to make money, that becomes a problem because essentially that's like a tax every time to do a trade."

Competitors hate the idea that a better-equipped competitor can charge a tax on their transactions.

"What's at stake here? It's not only a level playing field, but it's a sense that the game is fair," Mr. Doyle says.

Indeed, high-frequency traders use every competitive advantage they have, exploiting regulations designed for their benefit and even making deals with the nation's now for-profit exchanges: They pay for extra-high-speed connections so they can gain a couple milliseconds – the time it takes a honeybee to flap its wings just once.

To be sure, the relentless speed and constant trading of securities have served a valuable and broader purpose: The differences in the spreads between securities' bid and ask quotes have narrowed significantly over the years, making market prices more accurate and trustworthy for investors – saving them billions of dollars.

And a host of studies show that the market's "liquidity" – that is, the ability to buy and sell stocks easily – has greatly improved since the advent of electronic markets, including high-frequency trading.

For now, this kind of trading may actually be on the decline.

Algobots used to rake in $0.001 to $0.0015 per share on each trade a few years ago, but now they can glean only an average of $0.0005 to $0.00075 per share per trade. In addition, high-frequency traders are moving fewer shares. In 2009, they traded about 3.25 billion shares a day, but only 1.6 billion in 2012.

Total profits for the entire high-frequency trading industry in 2012 were about $1.25 billion, down from its peak of about $5 billion in 2009, according to Rosenblatt Securities in Manhattan. To put this in perspective, a single big bank on Wall Street can earn $5 billion in just a quarter.

Unknown risks to national security

Yet beyond questions about fairness or who profits from high-frequency trading, many on Wall Street are worrying about the unknown effects of these autonomous algobots battling for market supremacy within the system's new horizons.

On May 6, 2010, an afternoon "flash crash" caused the Dow to plummet more than 1000 points in a matter of minutes – the biggest intraday decline in the index's history – only to recover its losses 20 minutes later. This is sometimes cheekily called the "Crash of 2:45" – a stock market crash and recovery measured in minutes rather than years.

Then in August 2012, one of the algorithms of a major player in high-frequency trading, Knight Capital Group, went berserk, accidentally buying and selling $7 billion worth of shares at a $2.6 million-per-second clip. The company lost nearly half a billion dollars in a day, or about 40 percent of its value. Traders have referred to this as "the Knightmare."

Those two incidents exposed a potential national security risk, analysts say.

"That's what I'm concerned about," says Mr. Bates, who is also a member of the Technology Advisory Committee for the US Commodity Futures Trading Commission, a federal regulatory agency. "If you just look at some of the things that have happened ... I mean, what would happen if a coordinated attack by whoever, Al Qaeda, maybe, or some kind of cell that seizes control of a hedge fund, drives the market off a cliff?"

Bates, like many others, says that one of the most important new regulations should be a mandatory audit trail, so regulators can piece together what happened should a runaway algorithm wreak havoc with the system.

But mostly, experts say, regulatory agencies need to catch up technologically and have their own real-time high-frequency bot to monitor everything going on in the matrix.

"They are behind, but they're catching up," says Jones. The SEC recently bought a high-frequency program called MIDAS from a high-frequency trader. "They've done a lot of hiring and thrown a lot of resources at it to try to catch up, because they realized that they were really behind and didn't understand the markets."

[Editor's note: An earlier version of this article misstated the time unit by which high-frequency trading is measured. It is milliseconds.]