Why Google is letting you store 50,000 songs in the cloud for free

Loading...

Google is upping the ante in music storage.

The company announced Wednesday that users will now be able to upload and store – for free – up to 50,000 song files in the cloud via Google Play Music.

That’s more than double Play Music's original limit, not to mention twice the 25,000 that Apple allows for premium users through iTunes Match – and that comes with a price tag of $24.99 a year. Amazon Music lets users store up to 250 songs in the cloud for free, but a subscription is required to access the service's 250,000 song limit.

“This has been a long standing request from users,” Google said of the change, according to 9to5Google.

Songs can be uploaded from a user’s iTunes collection or other music folders, and can be played on Android and iOS devices and the web.

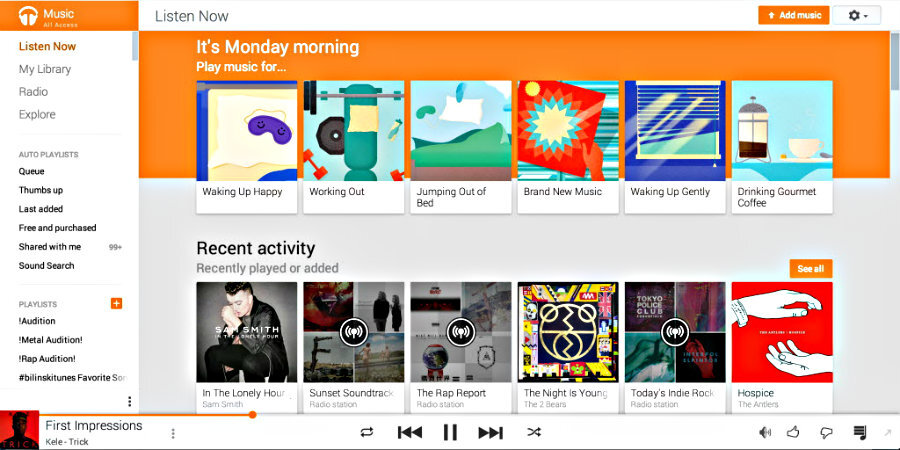

The uploaded songs also work in tandem with the streaming service Google Play Music All Access, the company’s $10-a-month Spotify competitor: Subscribers can combine their own music files with any of the 30 million tracks available in the All Access library.

Google’s expansion of its free storage space has so far received a warm welcome. On Twitter, Gizmodo called it an “even better Spotify alternative,” while The Verge’s Chris Welch pointed out that “Apple and Amazon don’t even come close.”

The service isn’t perfect. Mr. Welch noted that Play Music doesn’t allow immediate manual uploads, instead matching users’ libraries with its own by default. Only when a mismatch occurs does the “Fix incorrect match” option appear, letting the user’s file upload.

Still, it’s hard to ignore 50,000 free slots, especially when “from the looks of it, there’s no fine print,” Welch wrote.

The rise of the cloud storage business is just one aspect of the changes that continue to rock the post-Internet music industry. The Atlantic summed it up:

First, Napster and illegal downloading sites ripped apart the album and distributed song files in a black market that music labels couldn't touch. Second, Apple used the fear and desperation of the record labels to push a $0.99-per-song model on iTunes, which effectively destroyed the bundling power of the album in the eyes of millions of music fans (even though country album sales are still pretty strong). For a decade, music sales plummeted. Third, digital radio and streaming sites got so good that now many music fans wonder why they need to buy albums in the first place. So, they don't.

What, then, is the point of a cloud service, and why is Google trying to move in on that market?

The most likely answer is that even the best streaming sites don’t have rights to all songs, according to CNET associate editor Sarah Mitroff.

Beatles fans, for instance, will have to go beyond Spotify and Pandora to get their fill of the Fab Four, Ms. Mitroff wrote. Taylor Swift also pulled out her music from these services, and other artists are considering doing the same.

“But,” Mitroff pointed out, “if you have the song files from those artists, you can upload them to Play Music and stream them on your own.”

“It's the best of both worlds,” she wrote.