Why can't renewable jet fuels take off?

Loading...

Alaska Airlines on Monday fueled one of its commercial flights from Seattle to Washington, D.C., partly with jet fuel made of wood scraps from the forests of the Pacific Northwest. At a time of growing carbon emissions in aviation and other transportation industries, the demonstration flight sought to show the world that it’s possible to extract sugars from wood – an arduous process – to convert them into jet fuel.

“Generally, a lot of people believed that it’s too complicated to use wood sugars; they’re wrong,” said Patrick R. Gruber, chief executive of biofuel-maker Gevo. The publicly-traded company based in Colorado converts isobutanol alcohol from sugars extracted from feedstocks such as corn, cane, and wheat into jet fuel.

Gevo made the biofuel for the demo flight as part of a five-year study backed by $40 million from the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). The company partnered on the project with Alaska Airlines and the Northwest Advanced Renewables Alliance at Washington State University, a group that created the sugar-extracting method as a way to reuse the woody waste leftover from commercial logging in Washington, Oregon, Idaho, and Montana.

On Monday’s flight, 20 percent of the wood-derived jet fuel, or kerosene, was mixed with traditional, petroleum-derived kerosene. And while a 20-percent infusion of wood-fuel on future Alaska Airlines flights could save as much carbon-dioxide emissions as taking about 30,000 passenger cars off roads for a year, according to the airline, Alaska Airlines won’t be switching its fleet over any time soon.

“There needs to be enough biofuel available to make this a reality,” says company spokeswoman Bobbie Egan. The wood-derived fuel is nowhere near commercialization, but the airline hopes to start blending in some type of biofuel on its flights by 2020, she says.

The idea of making fuel from renewable resources has been around since the invention of cars – US oil refiners (for now) are required to mix biofuel with regular gasoline for use in cars to reduce harmful emissions. But certain barriers have made it impossible so far to use these alternative fuels on a large scale.

“We’ve seen progress on certification and safety, but we’ve seen less progress on supply and on sustainability,” says Daniel Rutherford, marine and aviation program director at the International Council on Clean Transportation (ICCT), a nonprofit research organization that informs environmental regulators.

According to Dr. Rutherford, a lot of different biofuel types and blends have been deemed safe for use, but they are still more expensive than traditional fuel. For a couple of June test flights, Gevo’s corn-based fuel cost Alaska Airlines six times more than the airline pays for regular jet fuel, according to Egan.

Jet fuel today costs less than $1.50 per gallon. Given that fuel is an airline’s biggest expense, the difference, at least at current prices, is significant.

Dr. Gruber, of Gevo, says that the company’s most popular fuel, made from corn, would be cost competitive with $65-per-barrel oil. Conventional oil has been historically cheap in recent years, now costing just under $50 a barrel.

There are other major strikes against renewable fuels, including those made from corn or from palm oil. If they were more widely used, they would compete for dwindling parcels of available food-growing land in some regions, or may take more energy to produce than they aim to save. These crops also need a lot of land to grow. The oil palm, for example, which produces an oil that is widely used for fuel and many other products, is responsible for massive deforestation in Malaysia and Indonesia.

“Whether or not a biofuel is good for the environment and good for climate depends on how it’s made or what it’s made from,” Rutherford points out.

Still, some airlines are heavily investing in the most promising of alternative fuels, especially as the industry works to cut its greenhouse gas emissions. Airlines are responsible for 1 percent of global emissions, though that’s expected to triple by the middle of this century. And while there aren’t regulations in the US or globally to limit airline emissions, the possibility is always looming. Just this year, UN’s International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO), a de-facto regulator of airlines globally, proposed carbon dioxide emissions standards for aircraft.

Also, oil prices will rise again.

“Traditional petroleum-based fuel is volatile; it’s possible that cost is going to increase in the future, so investing in biofuel acts as a hedge against the volatility of traditional, petroleum-based fuel,” says Charlie Hobart, a spokesman for United Airlines. The company last year invested $30 million in Fulcrum Bioenergy, which will build refineries around the country to provide fuel made of garbage for United to blend on flights starting in 2018.

Additionally, United has a contract with oil refinery Altair Fuels, which this year started to provide biofuel made of non-edible natural oils and animal waste. Thirty percent of this biofuel is blended with traditional jet fuel on all of United’s flights out of Los Angeles. Using the biofuel, United says, reduces carbon emissions by up to 60 percent compared to standard jet fuel.

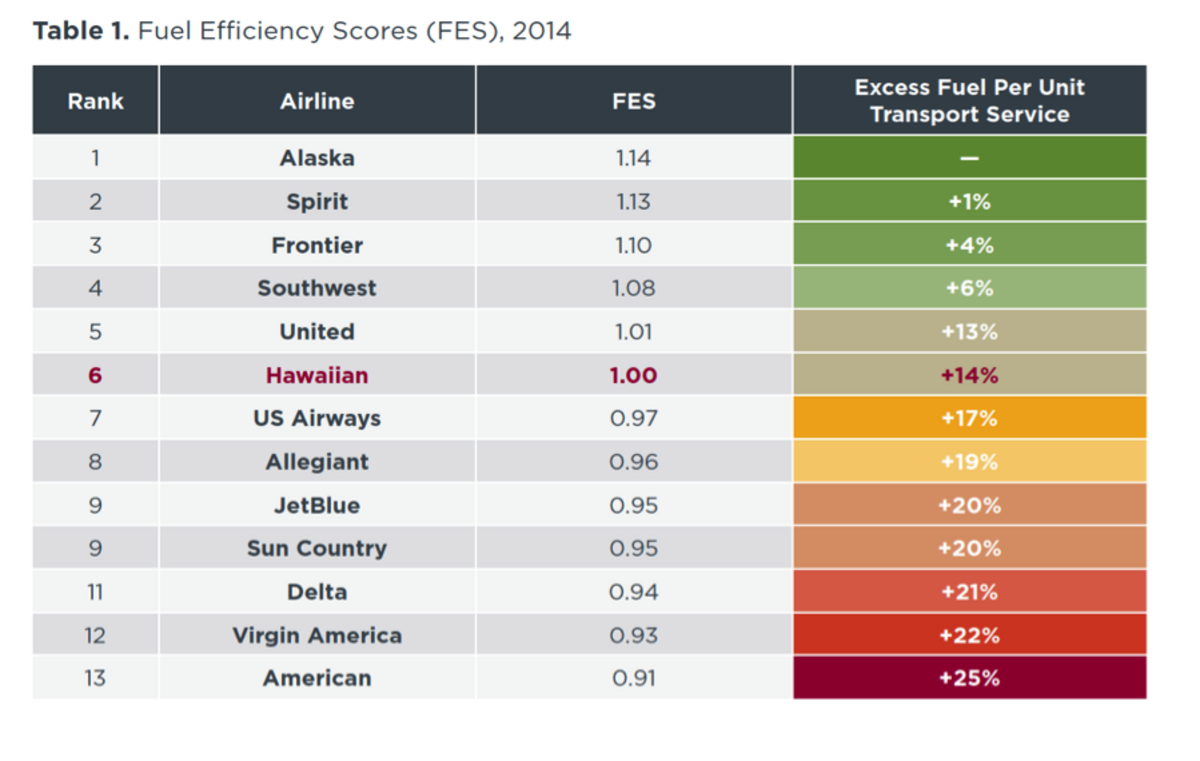

Biofuels are not the only way to improve airline efficiency, though, says Rutherford. Airlines can improve the efficiency of regular fuel by doing things like upgrading their fleets and using efficient flying routes. Based on those factors, the ICCT ranked United sixth-most efficient out of 13 American airlines in 2014, controlling for the number and length of flights each airline operates.

Alaska Airlines, with its new fleet of planes and state-of-the-art operational practices, has ranked #1 every year since the organization started tracking airlines in 2010.

“I think they definitely deserve credit for that,” Rutherford says.