OPEC production cuts: What they mean from US gas pumps to African wells

Loading...

| Boston

For years, the world oil market has acted like a seesaw, balancing the world’s motorists against oil producers. After the Great Recession, producers were on top, raking in profits from high oil prices.

Then, three years ago, the positions shifted. Oil prices plunged and motorists were riding high. Cheap gasoline put billions of dollars in their pockets, while producers struggled to pay bills.

Now, the teeter is beginning to totter again – and motorists, as well as trucking companies, airlines, and other oil consumers, could land with a thud as oil prices rise.

No one knows when this will happen. Prices could push to $100 a barrel or more by the end of next year, according to the most aggressive forecasts. Or they could stay at current levels for the next five years before rising.

What is clear is that the forces holding prices down are beginning to dissipate. A meeting of OPEC nations is bringing some of the changes into focus, and it’s a reminder that the industry that literally fuels the global economy defies simple narratives. Oil-producing nations may no longer have quite the clout that they once did, but neither is an “end of oil” shift to clean energy already ascendant.

And all this has repercussions for both consumers and the wealth of oil-reliant governments from Russia to Africa.

“Markets don't work quietly,” says Dan Dicker, an oil trader and analyst who writes the Energy Word blog letter. “When trends start developing, they go overboard – on both sides.”

The latest move came Thursday when the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries announced that it is extending for nine months an existing agreement to cut production. The original agreement called for OPEC members to cut 1.2 million barrels per day (b.p.d.) of production and for 11 nonmembers to trim an additional 600,000 b.p.d. Prices shot up 9 percent in a day.

If OPEC can maintain the discipline it has shown in the previous six months, it could begin to draw down the glut that has built up over the past three years because of overproduction, according to the International Energy Agency.

Already, the IEA reports that oil supply and demand are in rough balance and demand is climbing.

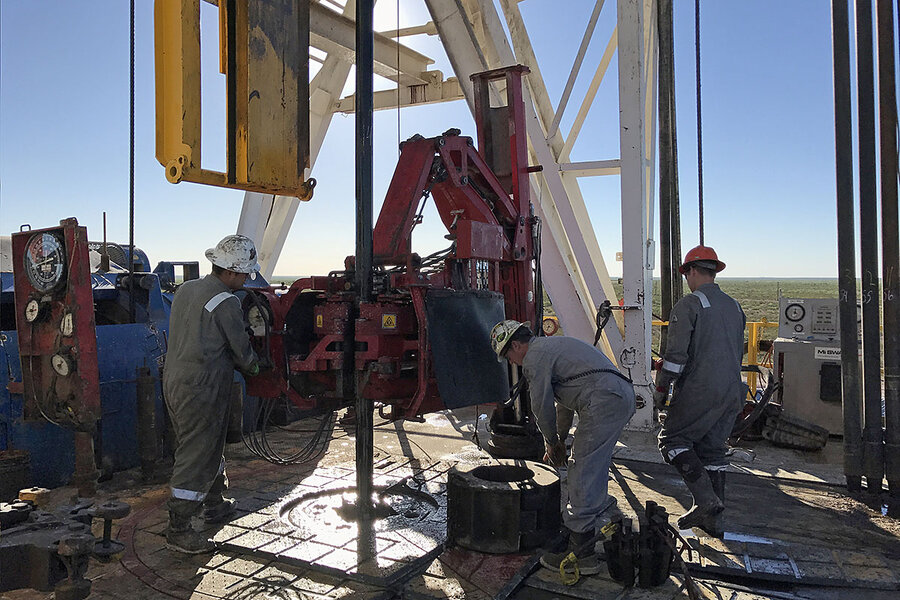

US fracking's surprising rebound

Looking beyond the next five years, oil prices appear bound to go up because the oil majors slashed their exploration budgets when prices were low. Thus, when maturing fields fall out of production in a few years, there will be very few oil discoveries to replace them right away.

The spoiler, which could keep prices weighed down for a while, is the US shale industry. Left for dead 18 months ago, when oil prices dipped below $40 a barrel, US producers have staged an unexpected comeback, slashing costs and ramping up production. US crude output has jumped 10 percent in a year, and now nearly rivals the leaders, Russia and Saudi Arabia.

Shale companies could boost their output by nearly 800,000 b.p.d. this year, according to the IEA. That would counterbalance nearly half the cuts that the OPEC deal is supposed to maintain.

US output could grow even more if oil prices don’t crash again.

“We expect the US can grow oil production for 10 years or a little longer,” R.T. Dukes, research director for energy consulting firm Wood Mackenzie, writes in an email. That assumes that oil prices gradually move up to around $70 or $80 per barrel. But even in the current range of $45 to $55, “we think the major plays will grow.”

That makes the US shale industry – and the jobs that go with it – a big winner in the current environment.

A wild card: electric cars

But a rise in oil prices could make winners, also, of both green energy alternatives and oil-reliant nations in places like Russia and Africa.

The higher prices go, for one thing, the more consumers and carmakers have an incentive to invest in electric cars.

“For the first time in a century, there is a real chance that the automotive ecosystem could change considerably in the years ahead,” says Jim Burkhard, head of oil market analysis at market researcher IHS Markit in Washington. It could end “oil’s de facto monopoly as a transport fuel.”

A twist, of course, is that the faster a transition toward electrified transport occurs, the more it will dampen demand for oil. But it will take a minimum of 15 years for electrification to eliminate growing oil demand, says Antoine Halff, senior researcher at Columbia University’s Center on Global Energy Policy in New York. But even if it doesn’t happen for years, “a peak in demand for 2040 has implications for how the Saudis should maximize their resources starting now.”

Russia vs. Venezuela

In the near term, geopolitics is also in play. Oil-exporting nations that have been struggling economically would benefit from a price rebound. One of them is Russia, which has agreed to cooperate with OPEC by trimming back production. Among the most financially stressed of the oil-producing nations, Russia is finally showing signs of coming out of its deep recession.

By contrast, Venezuela, the other nation most stressed by low oil prices, looks to be a loser. A price recovery will probably not come in time for the regime, which has so mismanaged the economy that citizens are rioting in the streets.

Big consequences could also be expected across much of Africa, with its many oil-producing nations from North Africa to further south.

Several sub-Saharan African countries – prominent among them Nigeria, the continent’s largest economy, and Angola – have staked their post-colonial fortunes on oil, and grown to become some of the world’s largest producers. But the oil producers, which include countries like the Republic of Congo and Sudan have often fallen prey to the toxic mix of corruption, low development, and economic volatility commonly dubbed the “resource curse” – a shorthand for the paradoxically adverse effects that resource extraction tends to have on developing economies in Africa and elsewhere.

Africa's mixed response

Africa’s oil producers are undoubtedly behind the global curve in diversifying their economies, says Mercy Ojoyi, a researcher in the African resources program at the South African Institute of International Affairs, and an expert on sustainable development in Africa.

“We certainly aren’t seeing any African Dubais yet. They just don’t have the diversified economies at this point, though many are trying to move in that direction,” she says. Still, for the time being “they continue to suffer heavily economically and socially when prices change.”

Smaller countries like the dictatorial Equatorial Guinea, which has had the same president for 38 years (the longest-serving president in the world), where oil accounts for 90 percent of government revenue, are among the worst-off at present.

“There’s essentially no economic activity there besides the oil and gas sector,” says Ben Payton, head of the Africa division for Verisk Maplecroft, a Britain-based consultancy. He says oil revenues tend to line the pockets of a small elite while the rest of the country remains shockingly poor. A rebound in oil prices by itself won’t change that.

But in Nigeria, the rise of alternative industries like telecom, construction, and agriculture – buoyed by the circulation of oil money in the country – at least partially insulates the country from price shocks and other fluctuations in the oil market.

Exempt from the last round of OPEC production cuts on account of infrastructure damage by militants last year, Nigeria has seen attacks go down and output rise. By June, Nigeria says it should be back to full production at 2.2 million b.p.d., up 1 million b.p.d. from April’s figures.

The Saudi factor

Globally, Saudi Arabia remains a key player to watch. It almost single-handedly created today’s glut of oil by ramping up production three years ago in a bid to maintain its market share and drive out US shale producers. When that didn’t work, it changed course six months ago and engineered the OPEC deal that has lifted prices and will begin to whittle down the glut.

The potential boom in electric transportation, like the resilience of US shale producers, complicates the Saudi calculus.

But no one knows how that will play out, Mr. Halff says. “History shows that the market can always surprise you.”

Ryan Lenora Brown contributed reporting from Johannesburg.