Are corporations going liberal? Conservative pushback on the rise.

Proposal 6 of the proxy statement for this week’s annual meeting at Bank of America reads like many proposals routinely pushed by progressive shareholders. It calls for the bank to split the CEO and board chairman positions between two people rather than concentrating power in the hands of a single person.

Nearby on the ballot were other proposals from outsider shareholders to curb fossil-fuel loans and to examine racial equity in the bank’s operations.

But Proposal 6 didn’t come from progressives.

Why We Wrote This

A story focused onFor years corporations have faced pressure from the left to pivot beyond “shareholder value” to think of wider stakeholders and longer-term risks such as climate change. But that so-called ESG movement faces rising criticism.

It was sponsored, instead, by the National Legal and Policy Center (NLPC), a conservative nonprofit in greater Washington that is a leader in the fight against environmental, social, and governance – or ESG investing. For decades, progressives have used ESG shareholder activism to convince corporations to support everything from greenhouse gas mitigation to gay rights. By copying their tactics and even the language of their shareholder proposals, conservatives hope to convince American corporations to stop supporting liberal causes.

“The corporations have swung too far to the left politically and unnecessarily and improperly,” says Paul Chesser, director of corporate integrity at the conservative policy center. “We’re not calling for them to embrace conservative politics…. We’re calling upon them to just stay out of these divisive political issues.”

What’s underway is a messy fight for the soul of the corporation. In the end, the battle may reveal how much of ESG is enduring, how closely it aligns with traditional profit motives, and whether boundaries between business and political activism are being redrawn – and, thus, how much the corporation has changed in recent years.

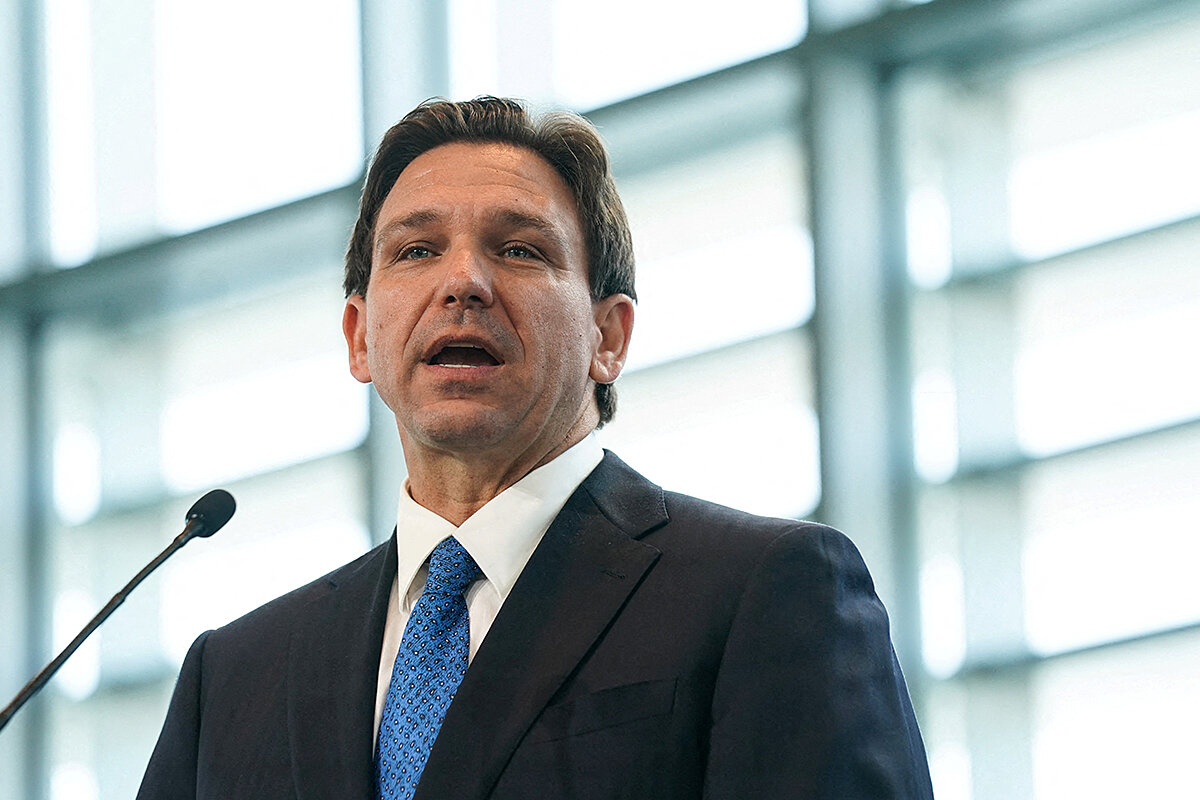

While conservative criticism of ESG initiatives has been building for several years, the movement was pushed on the national stage a year ago after Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis tried to punish Disney for opposing a Florida ban on sexual orientation and gender identity instruction in public schools. The governor tried to strip the entertainment giant of its special status as a governing body for the land around Disney World, got outmaneuvered by the company, and is now fighting to control future land development around the theme park. On Wednesday, Disney sued the governor for “weaponiz[ing] government power.”

A backlash on political and financial fronts

The conservative backlash is playing out across two fronts. First is shareholder activism. Conservative shareholder proposals surged last year after Peter Flaherty, the CEO and chairman of the conservative legal and policy center, brought in Mr. Chesser to direct shareholder advocacy. The number of anti-ESG proposals jumped by 60%, by one count, and the center itself had 10 of the top 12 conservative shareholder proposals that garnered more than 5% support, according to Morningstar.

These proposals, like this year’s Proposal 6 at Bank of America, can be hard to distinguish from ones that liberal ESG proponents use. At Boeing, the group is pushing for an audit of the company’s risks from doing business in China. Getting a proposal on the ballot also allows the sponsor to speak. And in the case of Bank of America’s Tuesday annual meeting, Mr. Chesser used his three minutes to publicly detail the conservative center’s opposition to the bank’s chairman and CEO, Brian Moynihan.

He criticized various bank loan programs targeted at non-white customers. Whereas the bank defends such programs for reversing decades of little to no access to capital for people of color, Mr. Chesser calls them racist because they leave out white people. Proposal 6 failed with a still respectable 26%, according to preliminary results from Bank of America.

The second front is led by Republican states. Last month, 19 governors from Florida to Alaska announced an alliance to push back against President Joe Biden’s ESG agenda. “The proliferation of ESG throughout America is a direct threat to the American economy, individual economic freedom, and our way of life, putting investment decisions in the hands of the woke mob to bypass the ballot box and inject political ideology into investment decisions, corporate governance, and the everyday economy,” they wrote.

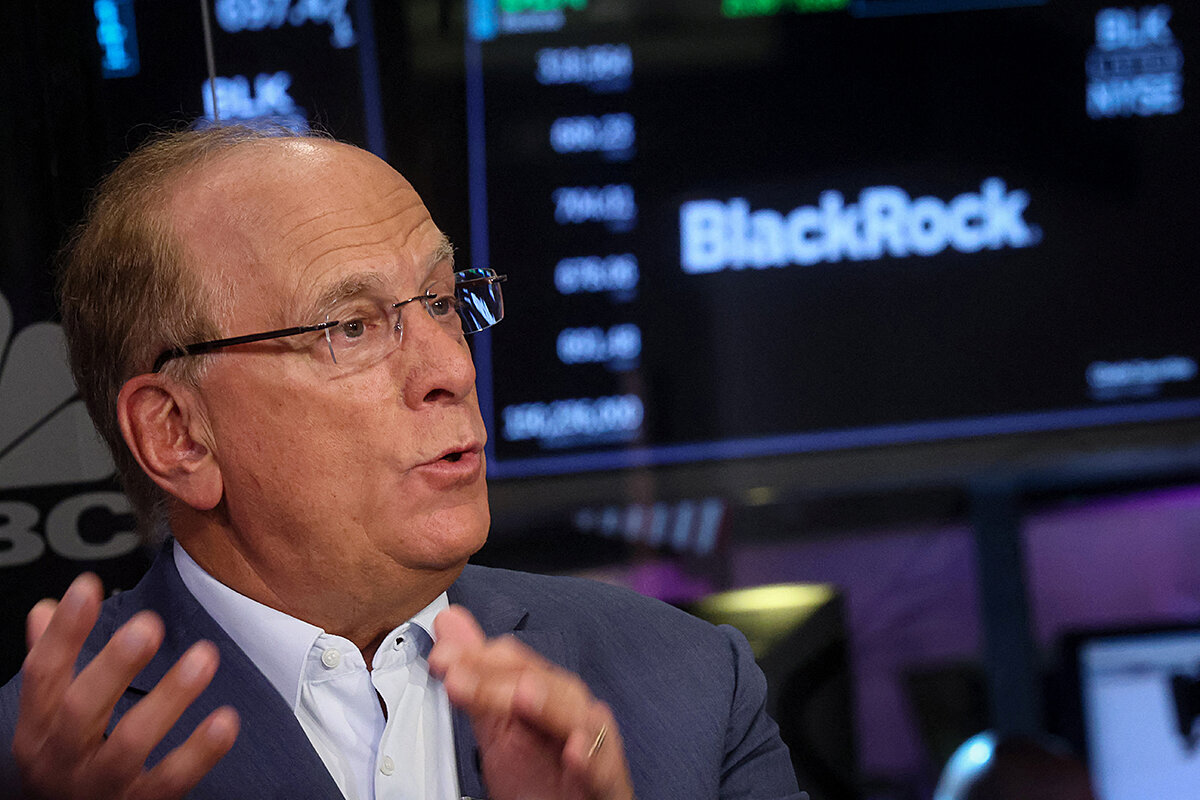

Many of those states have pulled state pension and other funds from big investment houses, such as BlackRock, saying they want to get the best possible return, unfettered by social decisions.

Conservatives’ frustration is palpable. For more than three decades, progressives have used shareholder resolutions to push companies on a host of issues, from climate change to transparent reporting on political spending to diversity and inclusion. They were such a small group, whose shareholder proposals initially got little support, that conservatives could safely ignore them.

But as the movement grew, mainstream investment houses began to view ESG as a line of business that could be profitable. They began to snap up ESG mutual fund families and other investing pioneers and started to create ESG portfolios for a much larger audience. The big investing houses, such as BlackRock and Vanguard, began to back some of the ESG shareholder proposals and corporations could no longer ignore the results.

Generational shifts

Also, in recent years, millennials and their successors, known as Gen Z, have told pollsters that they feel inclined to purchase goods and services from companies that share their values. High-profile companies that deal directly with consumers, sensing a business opportunity, began to speak out on issues relevant to this key consumer segment. While older Americans might be skeptical about issues such as climate change and gender equity, these younger consumers view them as important.

Suddenly, conservatives were seeing corporate America, which they thought backed their side (some 70% of CEOs and corporate board members are Republican), appearing to go “woke.” “Conservatives were asleep and they conceded the battlefield to the left,” Mr. Chesser says.

ESG critics argue that investing, say, state pension funds according to such principles is not living up to one’s fiduciary duty because something other than maximum profit is guiding investing decisions. The studies on ESG results are mixed. Theoretically such companies might outperform because they’re less likely to get sued for pollution or unequal pay for women. In practice, however, ESG mutual funds often exclude profitable sectors of the economy, such as alcohol, tobacco and guns. These exclusions make it hard for ESG funds to keep up with more general funds. On Tuesday, Louisiana launched an investigation into a climate change coalition to see whether two of its members, mutual fund giant Franklin Templeton and the California Public Employees’ Retirement System, had breached their fiduciary duty to investors.

The case for ESG as a fiduciary duty

But that charge may be hard to make stick because the ESG movement is much bigger than a collection of progressives who invest according to their values. A larger group of businesses and investors appear to be using ESG principles to assess the risk of their portfolios and businesses. They may disagree with progressives on, say, climate change policies. But they view it as their fiduciary duty to take into account the threat it might pose to business operations and in the form of climate regulation.

“If you look at the representative retail investor … it seems like they’re using the ESG factors to generate wealth rather than [forgoing] wealth to save the environment or something along those lines,” says Edward Watts, an accounting professor at Yale University who has studied investor behavior around ESG news events.

“We focus on sustainability not because we’re environmentalists, but because we are capitalists and fiduciaries to our clients,” Larry Fink, CEO of BlackRock, the world’s largest asset manager, said in his letter to shareholders last year.

Corporations have shifted – but more shifts to come?

Such moves come against the backdrop of a recent sea change in the way many corporations view their role in society. In contrast to the narrow view that corporations exist only to make their shareholders money, popular from the 1980s onward, corporations have returned to an older and broader view that companies exist to serve all their stakeholders, including employees, customers and their communities.

“The markets have already shifted,” says Andrew Behar, CEO of As You Sow, a leading nonprofit in shareholder advocacy. In 2019, the Business Roundtable officially embraced this idea of stakeholder capitalism, followed by the World Economic Forum a few months later. “The companies who are adopting justice and sustainability are the ones who are succeeding. They’re the ones customers want to have loyalty with. They’re the ones who investors want to invest in. They’re the ones who are going to thrive in the next five, 10, 20 years.”

Nevertheless, the rising pressure from the right appears to be yielding results. In December, investing giant Vanguard announced it was pulling out of the Net Zero Asset Managers group, which envisions a zero-emission economy by 2050. Bloomberg News reported that 11 major banks and money managers were adjusting their ESG communications to clients, sometimes avoiding the term in red states while playing it up in blue states. A recent Wall Street Journal poll found that 63% of Americans don’t want companies talking about social or political issues.

“The chilling effect of this anti-ESG movement may be that CEOs and boards are just not publicly talking about this as much,” says Fran Seegull, president of U.S. Impact Investing Alliance, which as an organization defines impact investing broadly to include strategies like ESG investing. “But we believe that the work of addressing ESG risks and opportunities is still getting done among businesses and investors because if you look at the constraints of the planet, if you look at the reality of a tight labor market, if you look at the driving forces that are shaping our macroeconomic and geopolitical environments, you need to take ESG factors into account. Corporations are taking this seriously.”

Both sides face political risks. For the left, climate goals can look out of touch when war-related oil shortages require more fossil fuel production, not less. For the right, the move to get corporations out of politics may require government intervention that makes some conservatives nervous.

Governor DeSantis’ moves to use state power to punish Disney risks tarnishing his pro-business image. When Kentucky initiated an investigation to see if local banks were using ESG investing principles and had signed on to the United Nations’ Net-Zero Banking alliance, the Kentucky Bankers Association sued Kentucky’s attorney general, calling it government overreach.

In between are the companies themselves, simultaneously accused of being too woke and not progressive enough. How they navigate the rising political clash will say much about the staying power of ESG.

“They’ve been under siege already without us being there,” says Mr. Chesser of the legal and policy center. “Now it’s going to be us opposing the left and us opposing when we think the corporations are improperly engaged in divisive politics. Maybe it complicates things for them a little bit more but, you know, it should have happened a long time ago.”