Workers expand strike against automakers amid dueling visions

Loading...

At issue in an expanding worker strike against major U.S.-based automakers are two visions of the future: one forward-looking that emphasizes innovation, one backward-looking that emphasizes fairness.

Both visions rest on underlying truths. Both are uncertain and therefore risky.

Why We Wrote This

A story focused onA weeklong U.S. auto strike hinges on two competing visions at a time of industry upheaval: workers focusing on fairness and companies eyeing the uncertainty of their electric transition. It’s high stakes for both.

For the automakers, the challenge is the costly transition to electric vehicles, which is occurring without a clear sense of how fast consumer adoption will occur or how profitable the EVs will become. The workers, for their part, say they bore concessions and hardships to help the Detroit automakers survive the Great Recession, and that restorative boosts in pay and benefits are long overdue.

The bargaining impasse took a somewhat hopeful turn Friday. Although the United Auto Workers union decided to expand its strike against General Motors and Stellantis from two plants to 38, it pointedly did not expand its strike against Ford, citing for the first time progress in talks.

UAW members are watching closely to see if the leadership’s novel strategy works. So are nonunion workers in battery plants that are popping up in the Midwest and the South. If the UAW can show that unionization means much better pay and benefits, these nonunion workers will be more likely to sign up.

Toby Higbie, a labor historian, says, “If they really want to have a chance of organizing in these new industries, [the union] has to show that it can bring home the goods for the workers.”

At issue in an expanding worker strike against major U.S.-based automakers are two visions of the future: one forward-looking that emphasizes innovation, one backward-looking that emphasizes fairness.

Both visions rest on underlying truths. Both are uncertain and therefore risky. And the stakes for both sides are huge.

For the automakers, the challenge is the costly transition to electric vehicles, which is occurring without a clear sense of how fast consumer adoption will occur or how profitable the EVs will become. The workers, for their part, say they bore concessions and hardships to help the Detroit automakers survive the Great Recession, and that restorative boosts in pay and benefits are long overdue.

Why We Wrote This

A story focused onA weeklong U.S. auto strike hinges on two competing visions at a time of industry upheaval: workers focusing on fairness and companies eyeing the uncertainty of their electric transition. It’s high stakes for both.

The bargaining impasse took a more hopeful turn Friday. Although the United Auto Workers union decided to expand its strike against General Motors and Stellantis from two plants to 38, it pointedly did not expand its strike against Ford, citing for the first time progress in talks. In a statement, Ford confirmed the progress but added there were “significant gaps to close on the key economic issues.”

The auto industry is changing fast. Prodded by federal subsidies and state mandates, carmakers in the United States are committing massive EV investments to help the world curb emissions of heat-trapping gases in Earth’s atmosphere. Their global rivals are doing the same.

Companies like Ford and General Motors face two problems. First, they’re currently losing money on every EV they sell, and the only way to solve that appears to be to scale up massively. Second, American drivers aren’t embracing the technology with the same verve as the automakers – at least not given the vehicle choices and recharging options currently available.

“The companies and the government are ahead of where the public would like to be in this transition,” says Marick Masters, a business professor at Wayne State University in Detroit who follows labor and the auto industry.

For instance, Ford, the No. 2 EV carmaker in the U.S. behind Tesla, cited slow consumer adoption this summer when it pushed back its target to produce 600,000 EVs worldwide in 2023, now saying that won’t happen until 2024.

A long strike that curtails the automakers’ production, especially at plants that produce conventional cars, which still produce big profits, would create an additional challenge for the companies.

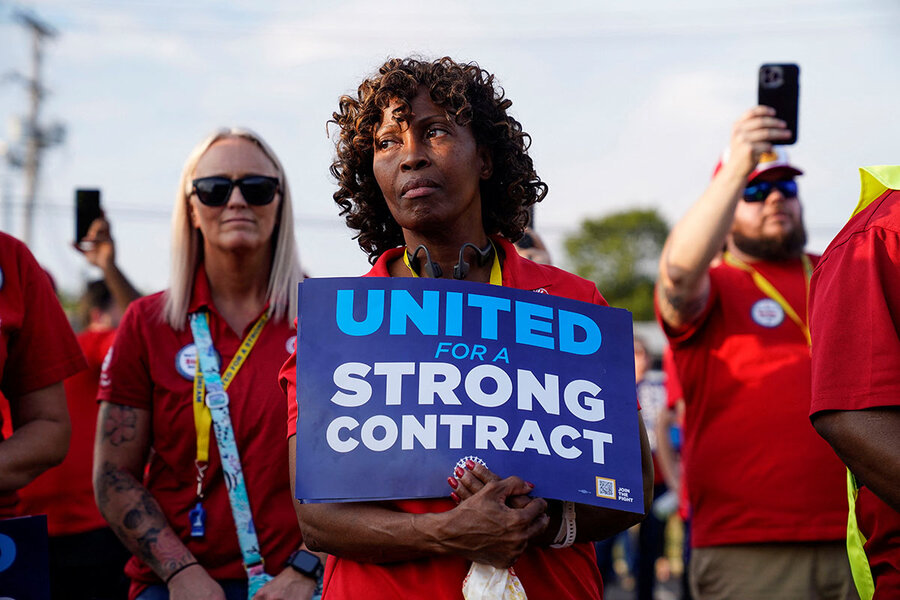

On the labor side, a new populist wind is blowing. Autoworkers made humiliating concessions during the Great Recession, when the federal government bailed out two of the three Detroit automakers (Chrysler, now owned by Stellantis, and GM). Now they are determined to win back what they lost, especially in the face of big profits for the automakers and soaring compensation for their CEOs. The union is demanding a 36% rise in income and the elimination of two-tier pay and temporary worker status that at present keep new UAW members from being compensated as well as their longtime counterparts.

But the union is also asking for much more, including the restoration of health care benefits for retirees, traditional pensions that new workers lost, and a program of extended pay and benefits for laid-off workers. And it’s asking for a new perk: 40 hours of pay for 32 hours of work.

“There is a very different kind of spirit right now” in the UAW, says Tod Rutherford, a geography and environment professor who studies labor and the auto industry at Syracuse University in New York. “People are just saying, ‘That’s enough. We’ve got to do something, make a stand.’”

The stakes are especially high for the union leadership. Narrowly elected in an unusual direct vote six months ago, following a corruption scandal at the union, dissident Shawn Fain has taken a much more confrontational approach to bargaining than the traditional leaders who ran the union for decades. He’s also adopted a novel strategy more reminiscent of the 1930s than of more recent times. Instead of striking one automaker and using the contract as a model to settle with the other two, the union has struck a single plant at all three automakers and is bargaining with all three simultaneously.

As long as the strike is short and limited to a few plants, Mr. Fain’s strategy helps the union conserve its $825 million strike fund. The UAW pays striking members about $500 a week. But if the strike drags on and escalates to include most of the plants at all three automakers, the fund will quickly dwindle.

UAW members are watching closely to see how Mr. Fain and his new strategy work. So are nonunion workers in battery plants that are popping up in the Midwest and the South, where “right-to-work” laws make it harder to unionize. If the UAW can show that unionization means much better pay and benefits, these nonunion workers will be more likely to sign up.

“This is about whether or not the union is going to be able to organize those workers in those industries,” says Toby Higbie, professor of history and labor studies at the University of California, Los Angeles. “If they really want to have a chance of organizing in these new industries, [the union] has to show that it can bring home the goods for the workers.”

EV batteries represent an existential threat for the union, a threat on par with the assembly plants foreign automakers set up in the nonunion South starting in the 1980s, says Professor Masters at Wayne State. The shift toward batteries could replace an estimated 30,000 to 40,000 UAW members, mainly those who make engines and transmissions for conventional cars. The Detroit automakers employ some 146,000 UAW workers.