Do public opinion surveys work anymore?

Public opinion surveys provide a wealth of information about beliefs in America and around the world. For example, they document how much public approval for same-sex marriage has been increasing, how Facebook has infiltrated many of our daily lives, and how humanitarian aid affects how citizens of other nations view America.

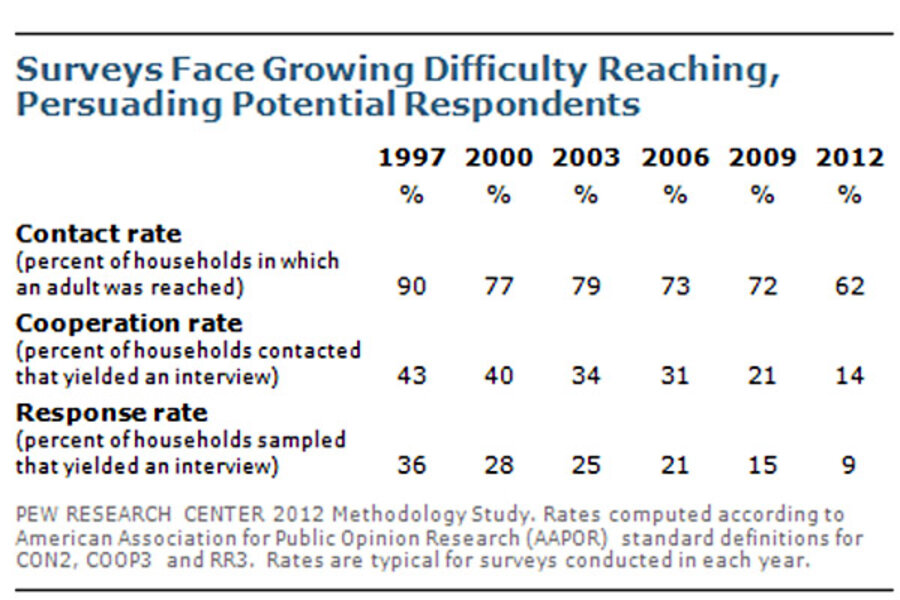

But pollsters face a significant challenge. As the Pew Research Center for the People & the Press notes in a new study, survey response rates continue to plummet:

Fifteen years ago, more than one in three of households responded to surveys. Today, that rate is less than one in ten.

That increases the cost of reliable surveys — to get a reasonable sample, you need to try to contact more households. Even more important, declining participation raises the question of whether the minority of respondents are representative of the population as a whole. The Pew Research Center study took a close look at that question:

The general decline in response rates is evident across nearly all types of surveys, in the United States and abroad. At the same time, greater effort and expense are required to achieve even the diminished response rates of today. These challenges have led many to question whether surveys are still providing accurate and unbiased information. Although response rates have decreased in landline surveys, the inclusion of cell phones – necessitated by the rapid rise of households with cell phones but no landline – has further contributed to the overall decline in response rates for telephone surveys.

A new study by the Pew Research Center for the People & the Press finds that, despite declining response rates, telephone surveys that include landlines and cell phones and are weighted to match the demographic composition of the population continue to provide accurate data on most political, social and economic measures. This comports with the consistent record of accuracy achieved by major polls when it comes to estimating election outcomes, among other things.

This is not to say that declining response rates are without consequence. One significant area of potential non-response bias identified in the study is that survey participants tend to be significantly more engaged in civic activity than those who do not participate, confirming what previous research has shown. People who volunteer are more likely to agree to take part in surveys than those who do not do these things. This has serious implications for a survey’s ability to accurately gauge behaviors related to volunteerism and civic activity. For example, telephone surveys may overestimate such behaviors as church attendance, contacting elected officials, or attending campaign events.

However, the study finds that the tendency to volunteer is not strongly related to political preferences, including partisanship, ideology and views on a variety of issues. Republicans and conservatives are somewhat more likely than Democrats and liberals to say they volunteer, but this difference is not large enough to cause them to be substantially over-represented in telephone surveys.

In short, opinion surveys likely overstate civic activity, but otherwise appear to track other observable political, social, and economic variables.