Why did Fama, Hansen and Shiller win the Nobel?

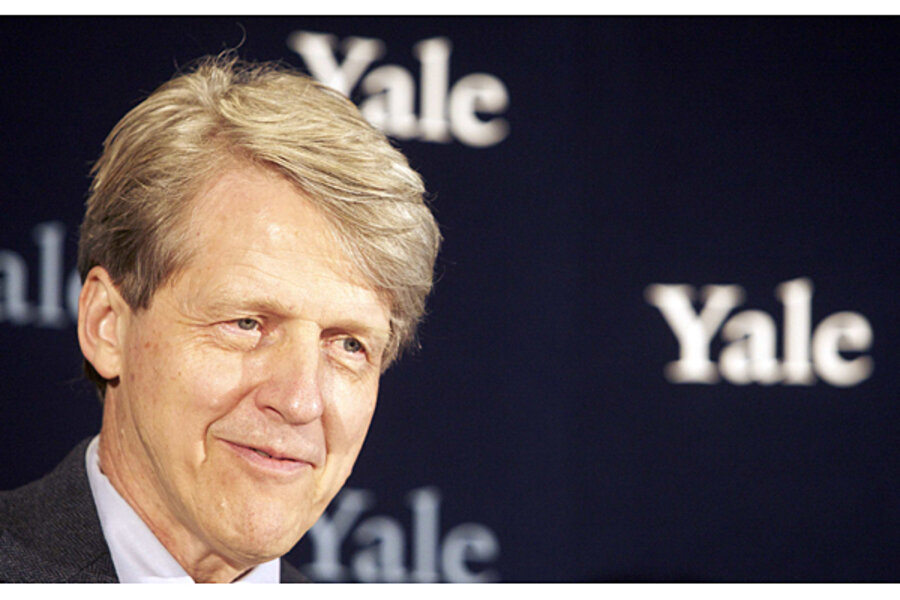

Eugene Fama, Lars Peter Hansen, and Robert Shiller won the Nobel Prize in Economics Monday for their work studying asset prices. In one sense, they are a motley trio: Fama is famous for emphasizing efficient markets, Shiller for emphasizing investor psychology and inefficient markets, and Hansen for high-tech econometric techniques that are used well beyond finance. The unifying theme is their shared interest in understanding the predictability, if any, of asset prices.

The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences posted an accessible summary of their work. Here’s the intro:

There is no way to predict whether the price of stocks and bonds will go up or down over the next few days or weeks. But it is quite possible to foresee the broad course of the prices of these assets over longer time periods, such as, the next three to five years. These findings, which may seem both surprising and contradictory, were made and analyzed by this year’s Laureates, Eugene Fama, Lars Peter Hansen and Robert Shiller.

Fama, Hansen, and Shiller have developed new methods for studying asset prices and used them in their investigations of detailed data on the prices of stocks, bonds and other assets. Their methods have become standard tools in academic research, and their insights provide guidance for the development of theory as well as for professional investment practice. Although we do not yet fully understand how asset prices are determined, the research of the Laureates has revealed a number of important regularities that are helping us to arrive at better explanations.

…

The predictability of asset prices is closely related to how markets function, and that’s why researchers are so interested in this question. If markets work well, prices should have very little predictability. This statement may seem paradoxical, but consider the following: suppose investors could predict that a certain stock would increase a lot in value over the next year. Then they would buy the stock immediately, driving up the price until it is so high that the stock is no longer attractive to buy. What remains is an unpredictable price pattern, with random movements that reflect the arrival of news. In technical jargon, prices then follow a “random walk.”

There are, however, reasons why prices may follow somewhat predictable patterns even in a well-functioning market. A key factor is risk. Risky assets are less attractive to investors, so on average, a risky asset will need to deliver a higher return. A higher return for the risky asset means that its price can be predicted to rise faster than for safe assets. To detect market malfunctioning, then, one would need to have an idea of what a reasonable compensation for risk ought to be. The issue of predictability and the issue of normal returns that compensate for risk are intertwined. The three Laureates have shown how to disentangle these issues and analyze them empirically.