Mitt Romney's tax plan: close, but not quite

Today the Tax Policy Center (TPC) released this analysis of the distributional effects of Mitt Romney’s proposed tax reform plan, and it got so much (deserved) attention that both President Obama and presidential candidate Romney talked about it. Too bad both candidates were speaking entirely as candidates and not as policy analysts or even as the supreme policymaker that we will elect one of them to be.

President Obama decided that the report was sufficiently unfavorable to the Romney plan as to make it great campaign speech fodder. As reported in Politico:

President Obama is set to attack Mitt Romney on Wednesday for pushing tax reforms that would cut taxes for the rich while raising the burden on other taxpayers.

It’s an argument that Obama often makes, but as he speaks in Mansfield, Ohio, it will come with the added weight of a new report from the nonpartisan Tax Policy Center — which is affiliated with the Urban Institute and the Brookings Institution — that backs up his claim.

“Just today, an independent, non-partisan organization ran all the numbers,” Obama is to say, according to excerpts of his speech released by the Obama campaign. “And they found that if Governor Romney wants to keep his word and pay for his plan, he’d have to cut tax breaks that middle-class families depend on to pay for your home, or your health care, or send your kids to college. That means the average middle-class family with children would be hit with a tax increase of more than $2,000.”

“But here’s the thing – he’s not asking you to contribute more to pay down the deficit, or to invest in our kids’ education,” Obama adds. “He’s asking you to pay more so that people like him can get a tax cut.”

Romney’s response? As reported by Lori Montgomery in the Washington Post:

The Romney campaign on Wednesday declined to address the specifics of the analysis, dismissing it as a “liberal study.” Campaign officials noted that one of the three authors, Adam Looney of Brookings, served as a senior economist on the Obama Council of Economic Advisers. The other two authors are Samuel Brown and William Gale, both of whom are affiliated with Brookings and the Tax Policy Center.

“President Obama continues to tout liberal studies calling for more tax hikes and more government spending. We’ve been down that road before – and it’s led us to 41 straight months of unemployment above 8 percent,” said Romney campaign spokesman Ryan Williams. “It’s clear that the only plan President Obama has is more of the same. Mitt Romney believes that lower tax rates and less government will jump-start the economy and create jobs.”

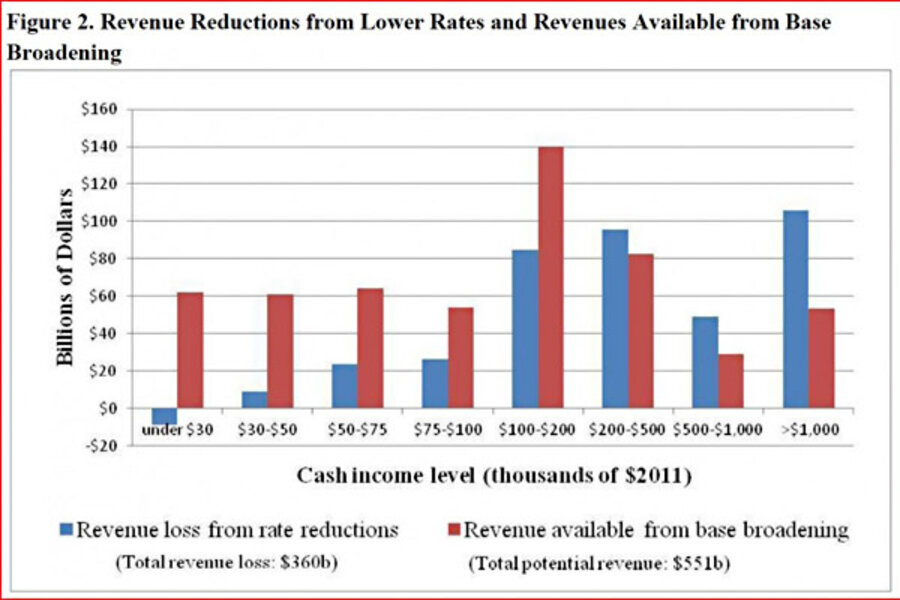

But what does the TPC analysis actually tell us–meaning us people who aren’t campaigning to be president–about the Romney tax plan? It’s well summarized by Figure 2 from the paper, above, which decomposes the bottom line conclusion that a revenue-neutral Romney plan would give generous tax cuts to the rich paid for with net tax increases on everyone else, into two parts: (i) how much the tax cuts from the tax rate reductions are skewed toward the rich; and (ii) how much the revenue offsets from (Romney-limited) base broadening are skewed toward lower- and middle-income households. Combined, we would end up with a revenue-neutral (relative to a business-as-usual, policy-extended baseline) and highly “regressive” tax reform, with relative and absolute tax burdens falling for “the rich” (defined here as households with incomes above $200,000–about the top 5%) and increasing for everyone else.

This makes the Romney proposal, specifically, a bad idea, but this should not be taken as a blanket indictment of any kind of tax reform proposal that tries to pay for low (or even lower) marginal tax rates by broadening the tax base. From a purely mechanical standpoint (leaving aside politics, I mean), both parts of the reform could be modified fairly easily to come up with a revenue-neutral but much more progressive (with average tax burdens rising more steeply with income) tax reform package. On part (i)–the rate cuts–just don’t cut rates so much (or at all) at the top. On part (ii)–the base broadeners–just make sure you reduce some of the tax expenditures that currently benefit capital income (which is highly skewed toward the rich) and ideally additionally limit other tax expenditures such that higher-bracket households don’t receive higher percentage subsidies. (The President’s proposal to limit itemized deductions to the 28 percent rate is an example of this latter strategy.) Romney goes wrong on both parts because he chooses to cut tax rates the most for the rich and at the same time refuses to reduce current tax subsidies that produce very low effective tax rates on capital income (and hence the rich). The TPC analysis explains that taking tax preferences on capital income completely off the base-broadening table (as Romney would do) means that the revenue-raising potential from base broadening is cut by about one third. So from my perspective, this particular version of a base-broadening tax reform scores poorly on fiscal responsibility grounds and not just distributional grounds.

But it seems that President Obama’s emphasis on the TPC analysis was to underscore that the offsets would imply higher taxes for most of us, even more than to complain about the proposed rate cuts lowering tax burdens on the rich. So I’d hate for the message heard from the President to be “we shouldn’t pay for tax cuts with base broadeners”–as the shorthand for a more accurate characterization of TPC’s conclusion that “we shouldn’t pay for large tax rate cuts on the rich with base broadeners that fall disproportionately on the non-rich.”

And by the way, the main lesson from the TPC analysis is also not what Romney suggests–that the Tax Policy Center is (suddenly) “liberal” and biased.