Income inequality: It's a problem. Here's why.

The Chairman of the White House Council of Economic Advisers, Alan Krueger, gave a great talk on inequality the other day, definitely worth a read (slides here, though why they’re not in the same doc as the talk is beyond me).

What’s particularly notable about Alan’s approach to the issue is his emphasis on the consequences of such high levels of income inequality as have developed here in the US. Too often, analysts just cite the problem without explaining why it’s a problem.

Alan focuses on inequality’s negative impact on macroeconomic growth, and thus job growth. That’s obviously extremely important, given our recent history (predating the Great Recession) as shown here.

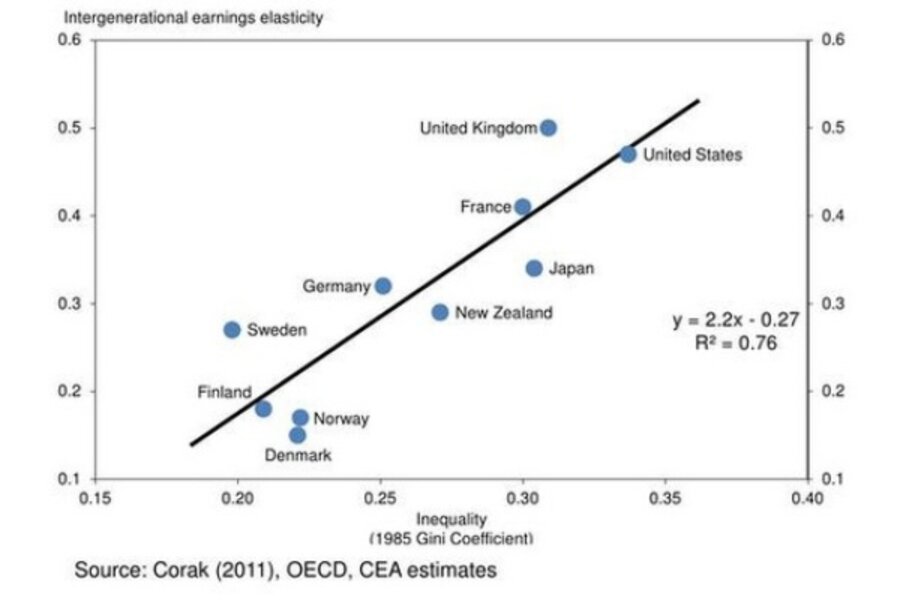

But the consequence I wanted to amplify was one I’ve discussed frequently: the link between higher inequality and diminished mobility. Check out this slide from Alan’s talk (above).

This scatter diagram compares something called the “intergenerational earnings elasticity” (y-axis) with a measure of income inequality on the x-axis. The former measure links kids’ earnings when they’re adults to that of their parents. It’s one of those “how-far-does-the-apple-fall-from-the-tree” metrics, wherein higher numbers represent less mobility. So, basically, this figure is asking whether countries with higher inequality are countries with less mobility. Clearly, the correlation is strong.

The points cluster around an upward sloping line, indicating that countries that had more inequality across households also had more persistence in income from one generation to the next…Countries that have a high degree of inequality also tend to have less economic mobility across generations.

This is extremely important in the political debate. We often hear politicians claim that we shouldn’t worry about growing inequality—Romney’s taken to calling such concerns “the bitter politics of envy”—because we’ve got the mobility to offset it. Not only is that wrong on the facts—you actually need more mobility to offset more inequality, and mobility has certainly not been increasing. But it also appears to be the case that higher inequality is itself associated with less mobility.

The transmission mechanisms for this are not well known, but surely have to do with educational access, employment networks, and so many other mobility enhancers that grow further from the reach of the have-nots in a highly unequal society…things like quality pre-school, good libraries, safe neighborhoods, environmental benefits, stimulating vacations and summer camps, and so on.

One of the saddest things is life—and one of the most wasteful, from the economy’s perspective—is a child blocked from realizing his or her potential. That’s what’s embedded in the slope of that graph and it’s something this nation needs to elevate to its top problem.

Here’s a thought: instead of all these budget deficit commissions that never amount to anything anyway, how about we get serious about tackling income mobility?