How Eisenhower and Congressional Democrats balanced the budget

Loading...

The election results did not change the political status quo, and the status quo has not been conducive to solving the nation’s festering fiscal problems. In his victory speech President Obama pledged to seek bipartisan cooperation in solving problems, though it is not going so well so far. But we better hope that in the end he succeeds. That is the only way to avoid the fiscal cliff and cure the long-run fiscal imbalances that threaten our economic wellbeing.

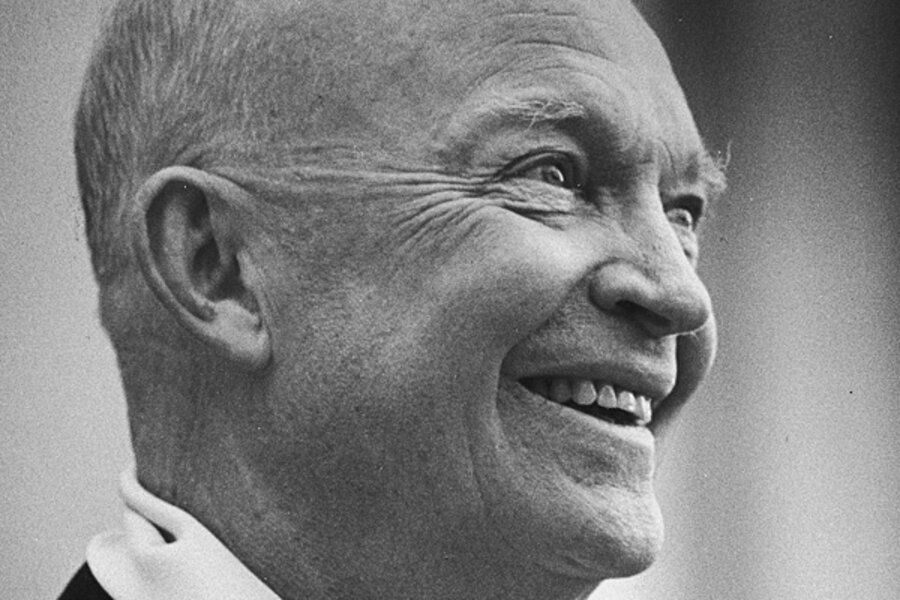

Given the challenges faced by the president and Congress, it is instructive to look back almost 60 years to a time when divided government did not mean gridlock and intense ideological battles did not lead to paralysis. Unlike most presidents who followed him, Dwight Eisenhower truly believed that budgets should be balanced. Consequently, he was embarrassed when by early 1959 the budget deficit was heading toward $13 billion.

Today, that seems very small but it was the largest deficit since the aftermath of World War II. Eisenhower was determined to attain balance, and his 1960 budget incorporated severe spending restraint and only minor tax increases.

But budget balancing would not be easy. Democrats had won a landslide victory in the 1958 midterm elections and held large majorities in both the House and the Senate.

The composition of the political parties and the budget were very different in 1959 than today. The Democratic Party contained extreme conservatives from the South like Richard Russell and John Stennis and liberals like Hubert Humphrey and William Proxmire. Republicans ranged from “Mr. Conservative” Barry Goldwater to Jacob Javits, who might now be considered a liberal Democrat.

Defense constituted about half of federal spending, compared with 18 percent in 2012. Social Security amounted to only 11 percent, compared with 22 percent today. Medicare and Medicaid, which have been growing very rapidly for decades, did not exist.

Foreshadowing his farewell warning about the military-industrial complex, Eisenhower had been hard on defense throughout his presidency. He was especially tough on the Army, believing that large armies created a temptation to get into ground wars.

Yet, the Cold War was raging, the Soviet Union’s Nikita Khrushchev was bellicose, and there was much discussion of a missile gap. Early in 1959 it appeared as though Congress, prodded mainly by conservative Southern Democrats, would significantly exceed Eisenhower’s defense request. But the president held firm and Congress agreed to an aggregate figure almost equal to his request.

The most interesting budget battle of the year involved a major housing bill. First, Congress passed a version that greatly exceeded the president’s request. But Democrats were very sensitive to being labeled “big spenders,” so they pared the bill back. Eisenhower vetoed it anyway, arguing it would add to spending in future years. Lawmakers upheld his veto.

Congress then sent the bill back to the Oval Office with several changes aimed at satisfying the president. Surprisingly, Eisenhower vetoed it again, and yet again Congress upheld his veto. Congress revised the bill a third time, and finally the president signed it, although it still contained some items he opposed.

What explains Eisenhower’s great success contending with a Congress controlled by the opposing party, especially given recent history of presidential budgets being labeled “dead on arrival”?

There are two reasons. First, Eisenhower was amazingly popular. Over the eight years of his presidency, his approval rating averaged 64 percent. No subsequent president has come close to that. Congress took him on at its peril. Second, Eisenhower’s budgets were serious documents, and he was willing to strongly defend them in speeches and frequent news conferences, and by wielding the veto pen if necessary.

Recent budgets are often forgotten by the presidents who present them. Eisenhower issued 181 regular and pocket vetoes over his eight years to back his budget and other policies. George W. Bush issued 12, and until now Barack Obama has issued 2.

Even Eisenhower did not always succeed. He twice vetoed a public works bill that he thought started too many projects. His second veto was overridden—the only veto battle he lost in the first 6-1/2 years of his presidency—proving that even a popular president better not come between a politician and pork.

Nevertheless, the final 1960 budget was balanced. Admittedly, it was aided by a bit of luck and one big gimmick. The good fortune: The recovery from the 1958 recession turned out to be more vigorous than expected. The gimmick: A large contribution to the International Monetary Fund was artificially moved forward into 1959 so it would not count against the 1960 budget.

But none of that detracts from Eisenhower’s enormous success working with a heavily Democratic Congress. Lyndon Johnson, the majority leader of the Senate, and Sam Rayburn, the speaker of the House, deserve some credit as well. They knew when to fight and when to give in. Are there lessons that might help to resolve today’s fiscal gridlock? I’ll explore that question in tomorrow’s blog.

Rudolph G. Penner is an Institute Fellow at the Urban Institute. He was director of the Congressional Budget Office from 1983 to 1987.