What the Farm Bill means for conservation

Loading...

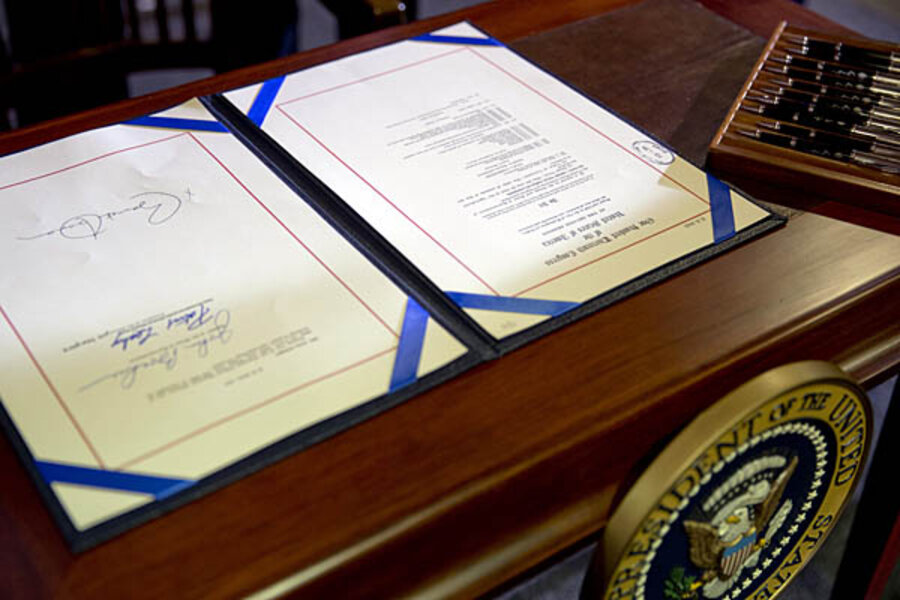

On February 7, after nearly three long years, President Obama signed the 2014 Farm Bill into law.

It’s a big deal – nearly $1 trillion big – covering everything from crop insurance to food stamps to research and rural development. And while it’s hard to find anyone who likes everything about the bill, the total package has most conservation advocates celebrating, both for some notable conservation victories and for what was kept out of the legislation.

The bill “boosts conservation efforts so that our children and grandchildren will be able to enjoy places like the Mississippi River Valley and Chesapeake Bay,” President Obama said at the signing ceremony. That kind of language was echoed in press releases from groups ranging from Ducks Unlimited to the National Farmers Union to the National Wildlife Federation.

Among the biggest conservation wins in the final bill is a provision linking crop insurance subsidies for farmers to conservation practices that protect land and water. Under “conservation compliance,” farmers who receive subsidized crop insurance premiums have to agree to adopt certain practices to protect soil and keep pesticides out of freshwater supplies.

Conservation compliance is a win-win for farmers and the nation’s waterways and wildlife, but it was by no means an easy win. A similar provision was stripped from the 1996 Farm Bill, and when the process that resulted in the current bill started almost three years ago, “conservation compliance was a fringe issue with very little chance of passage.” It was just one of many items on a very long priority list for most groups working on Farm Bill issues, and seemed likely to be traded away as a bargaining chip for other hoped-for measures.

But conservation compliance was also one of the few items that an impressive diversity of stakeholders – farmers, hunters, environmentalists – could agree on. So when these groups got together and made conservation compliance a top priority, things started looking more hopeful.

Given the jargon-laden white-noise that accompanies the Farm Bill debate, an important first step was to settle on simple language that would help reporters and decision-makers quickly understand this important issue. From the American Farmland Trust to the National Corn Growers Association to Senator John Thune (R-SD), supporters started referring to conservation compliance as kind of quid pro quo in which farmers who take advantage of taxpayer assistance pledge to adopt common sense conservation practices to protect the nation’s soil and water. With a unified coalition, Congressional champions and a compelling message, conservation compliance went from fringe to mainstream, and finally, to law.

Read more about the Farm Bill’s wins – and losses – in our round-up of the final bill’s conservation programs.