Bernanke wades into economic policy muddle

Loading...

The 20th century theories for battling recessions are looking a little tattered for today's economic storm, which is why the solutions now being proposed look ideologically messy.

Lifeline? Grab a bunch! economists and policymakers are saying. One alone won't work.

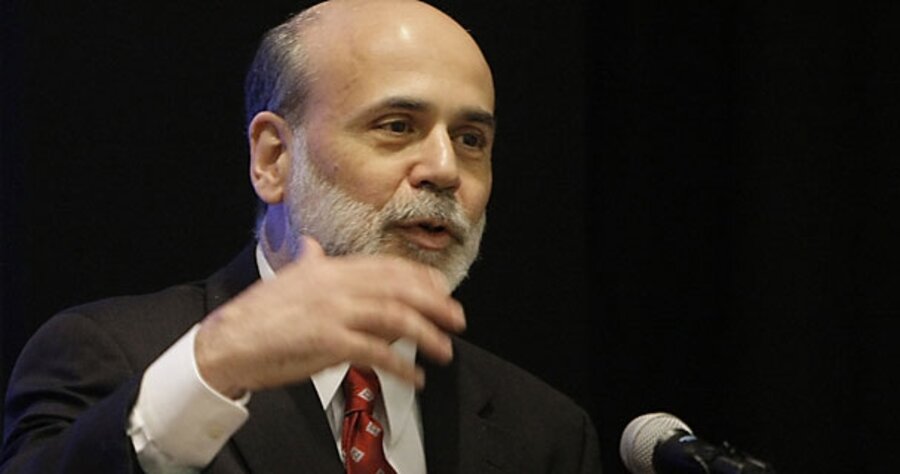

That theme emerged again Tuesday when Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke addressed the London School of Economics.

"The incoming administration and the Congress are currently discussing a substantial fiscal package that, if enacted, could provide a significant boost to economic activity," Mr. Bernanke in his most direct support yet of President-elect Obama's stimulus package. "In my view, however, fiscal actions are unlikely to promote a lasting recovery unless they are accompanied by strong measures to further stabilize and strengthen the financial system."

Stimulus, stimulus everywhere

Practically every country is contemplating a stimulus package, a direct legacy of John Maynard Keynes, the British economist who made deficit-spending cool back in the 1930s. In case you haven't noticed, Keynes is making a comeback.

For half a century, his theories provided the justification for governments to spend millions and billions of dollars when hard times hit. It was cheaper to go into debt and speed the recovery, the theory went, than to endure the economic and tax consequences of a longer downturn.

But if the theory worked, how come the stimulus-driven New Deal didn't? Most economists agree World War II pulled the US out of the Depression. Was the theory wrong or the stimulus too small?

Interest rates matter more

Enter the other big theorist of the 20th century – economist Milton Friedman, who argued that it wasn't a lack of stimulus that made the Depression so bad but the Federal Reserve's tight rein on the money supply. As a young economist, Mr. Bernanke expanded on that theory. Economist (now Obama adviser) Christina Romer also studied the Depression and other downturns and agreed that money supply, not stimulus, was the engine of recovery.

But that theory now looks suspect, too. Bernanke has spent the past 16 months cutting interest rates – they're now effectively zero – without much effect. The economy continues to deteriorate.

This has led to a vigorous debate over what to do. Many economists, even conservative ones, are now calling for a Keynesian stimulus, at least as a temporary measure to jump-start the economy.

But Bernanke is looking beyond that. "History demonstrates conclusively that a modern economy cannot grow if its financial system is not operating effectively," he told the London School of Economics.

With no more direct leverage on interest rates (they're at zero), the Fed is pumping more money into the economy by making huge loans to financial firms and buying up their debt. The US Treasury is buying up portions of companies considered crucial to the functioning of the financial system.

Where to go from here?

But this lack of clear direction leaves Americans dangling at the end of economic theories with no clear relief from the gathering storm.

That's not necessarily a bad thing. Flexible, ad hoc measures may be the right solutions in these times, if they can generate confidence and trust. Meanwhile, we probably need a new theory to explain why the old ones didn't work.