The power – and relevance – of Martin Luther King’s revolutionary love

Loading...

It takes a special kind of love to hold back when a Nazi just punched you in the face. It takes a special kind of love to hold back when your house has just been bombed. It takes a revolutionary love.

Martin Luther King Jr. wasn’t a pacifist. He wasn’t a coward. He was a revolutionary, for certain. His beliefs, and more importantly, his actions, changed the world. And while revolution, by definition, suggests a singular dramatic change, King went through several transformations during his quest for social and economic justice.

Those transformations deepened and refined his understanding and practice of nonviolence. But his goal was not personal. He worked to establish the “beloved community” – a society where opportunity was available to all and conflict was resolved peacefully.

Why We Wrote This

Martin Luther King Jr.’s practice of nonviolence – based on unconditional love – offers a revolutionary guide to healing strife and divisions today. This first installment in an occasional series explores the origins and promise of his legacy.

Today, in a world of division and strife, particularly over race and economic inequality, King’s legacy could hardly be more relevant. Now is not the time to relegate him to the history books or dismiss his ideas as impractical to the challenges of the moment. Rather, better understanding his legacy – including the less familiar and often glossed over parts – reconnects us to the most effective and powerful period of American protest since the Revolution.

This article begins an occasional series exploring that legacy. We’ll consider everything from the influence of his forefathers to his relevance to the Black Lives Matter movement. We’ll look at his strategies as an organizer and examine how the Rhetorical King differs from the Real King. The goal is to provide a refresher course of sorts for a time in need of King’s commitment to unconditional love.

Meeting fire with love

Two days after King’s Alabama home was bombed on January 30, 1956, he was persuaded to do what many of us might have done: he applied for a concealed carry permit so that he could have an armed guard at his home. What might have become of King’s ideological path if that permit had been approved?

Of course, such a permit would not be approved for an African American in the Jim Crow South, but that didn’t quench King’s thirst for justice. Long before that permit was denied, he had already determined how he would pursue justice, as evidenced in his commentary to neighbors the night of the bombing:

We are not advocating violence. We want to love our enemies. I want you to love our enemies. Be good to them. Love them and let them know you love them. I did not start this boycott. I was asked by you to serve as your spokesman. I want it to be known through the length and breadth of this land that if I am stopped this movement will not stop. … For what we are doing is right. What we are doing is just. And God is with us.

The boycott, of course, was the Montgomery bus boycott. King’s account of the boycott and his mindset during the crucial years of 1955 and 1956 have been chronicled in “Strive Toward Freedom,” published in 1958. The book does an exceptional job of capturing the duality of King – nonviolent, yet zealous. It’s a double-edged sword – a biblical description that fits King, both reverend and radical, to a T. His faith helped him speak to people in a way that divided soul and spirit, that judged the thoughts and the attitudes of the heart.

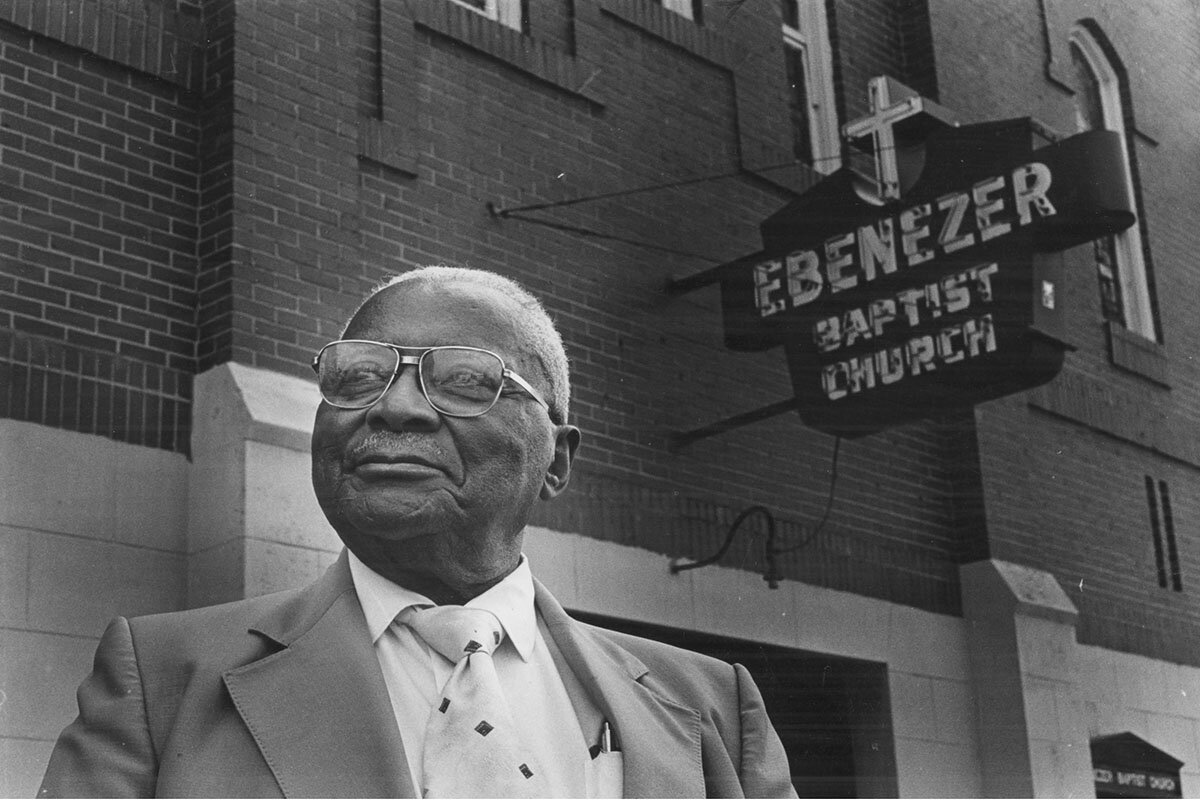

A family of preachers

Yet he did not arrive at this entirely on his own. A conversation about King must include his forefathers. Saying that he grew up in the church is an understatement – his father, grandfather, great-grandfather, brother, and uncle were preachers. Before King’s own theological studies sharpened his convictions, his father was a shining example of nonviolent resistance, as King shared in the first chapter of his autobiography:

A sharecropper’s son, [my father] had met brutalities at firsthand, and had begun to strike back at an early age. His family lived in a little town named Stockbridge, Georgia, about eighteen miles from Atlanta. One day, while working on the plantation, he keenly observed that the boss was cheating his father out of some hard-earned money. He revealed this to his father right in the presence of the plantation owner. When [t]his happened the boss angrily and furiously shouted, “Jim, if you don’t keep this n----- boy of yours in his place, I am going to slap him down.” Grandfather, being almost totally dependent on the boss for economic security, urged Dad to keep quiet.

My dad, looking back over that experience, says that at that moment he became determined to leave the farm.

Indeed, within months, his father moved to Atlanta, where he began high school at age 18 and continued his education until he graduated from Morehouse College.

King Jr. followed in his father’s footsteps, attending Morehouse prior to his studies at Crozer Theological Seminary. In the sixth chapter of Stride Toward Freedom, entitled “Pilgrimage to Nonviolence,” King outlines his intellectual journey and what he came to understand about the strength of nonviolent resistance:

The phrase “passive resistance” often gives the false impression that this is a sort of “do-nothing method” in which the resister quietly and passively accepts evil. But nothing is further from the truth. For while the nonviolent resister is passive in the sense that he is not physically aggressive toward his opponent, his mind and emotions are always active, constantly seeking to persuade his opponent that he is wrong. The method is passive physically, but strongly active spiritually.

Putting nonviolence into practice

This brings us to the time King was punched by a Nazi, Roy James, during a Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) in 1962. King was a literal picture of nonviolence, as shown in a photograph of the two men in conversation just minutes after the attack. James, who initially was remorseful after the assault, later became unrepentant.

King was just as willful and skillful in his response to the SCLC crowd as he was after his house was bombed. Praising their refusal to fight back physically, he said, “I am proud of what happened here today,” he said, “because it indicates to me that the message of nonviolent discipline has been learned.”

For Rosa Parks, who was at the SCLC meeting, King’s actions proved the power of nonviolence. Reflecting on the scene, she said, “His restraint was more powerful than a hundred fists.”

Whether responding to a bomb, a punch, or an arrest, King’s actions reinforced community – the beloved community. As The King Center explains, the beloved community is more than an ideal. It’s a tangible and realistic goal, achievable through a culture of nonviolence.

At the basis of this community is a revolutionary love, a biblical love known as agape. King describes it in “Stride Toward Freedom”:

Agape is not a weak, passive love. It is love in action. Agape is love seeking to preserve and create community. It is insistence on community even when one seeks to break it. Agape is a willingness to sacrifice in the interest of mutuality. Agape is a willingness to go to any length to restore community. …It is a willingness to forgive, not seven times, but seventy times seven to restore community.

We often praise King for his ideology of nonviolence, but we should also praise him for his spirit of resistance. He and the people around him were targets in every way imaginable, yet that did not stop King’s ambitions for a better way and a better world. His plan grew out of a revolutionary love; principles and steps were established. Out of this great love, King came to realize the need for not only racial justice but economic justice. In the end, he would strike out against the “triple evils” of poverty, racism, and militarism.

King’s revolutionary love started a movement that would change his world – and holds answers for us today.