A search that changes perceptions

Loading...

A year after he built his first telescope, Galileo published a small volume titled “The Starry Messenger,” in which he described how his primitive instrument had opened the heavens to his eyes and confirmed the orbits of planets and moons. First “I saw the moon from as near at hand as if it were scarcely two terrestrial radii away. After that I observed often with wondering delight both the planets and the fixed stars....”

The Italian astronomer’s major findings were that the moon was physically similar to Earth, with mountains and valleys; that the Milky Way was actually a collection of thousands of stars and not just a cloudy region in the sky; and that Jupiter had four moons orbiting it. That last finding was the most radical. It spelled the end of geocentrism, upending religious dogma and centuries of philosophical certainty.

In the 404 years since then, bigger and better telescopes have repeatedly revolutionized humanity’s perception of the universe. In a Monitor cover story (click here), Pete Spotts reviews the quarter-century career of a telescope that has been as world changing as Galileo’s: the Hubble. Pete tells its dramatic life story and details the key findings of what some astronomers believe is the most successful and productive experiment in the history of science.

And science isn’t Hubble’s only legacy. The contributions of the “people’s telescope” have also been aesthetic and artistic. Hubble’s incredible images -- especially that breathtaking snapshot of the Eagle Nebula, known as the “Pillars of Creation” -- have come to symbolize the ethereal beauty of deep space.

There’s even been ballet involved. Story Musgrave, lead repairman on the 1993 mission to repair Hubble, once described his intricately choreographed mission as a “zero-G dance” with bodies and tools. At one point in the five-day program, a fellow astronaut’s practiced move involved grabbing him and spinning him into position inside Hubble’s confined interior.

As with the global effort at the Large Hadron Collider and other research projects, modern science has moved far beyond the day of Galileo tinkering alone in his workshop. But even Galileo wasn’t a loner. He built his first telescope based on a description by Dutch lensmaker Hans Lippershey, his work was confirmed by German astronomer Christopher Clavius, and he validated the heliocentric theory of Nicolaus Copernicus. Science is Team Humanity’s hard-won body of knowledge.

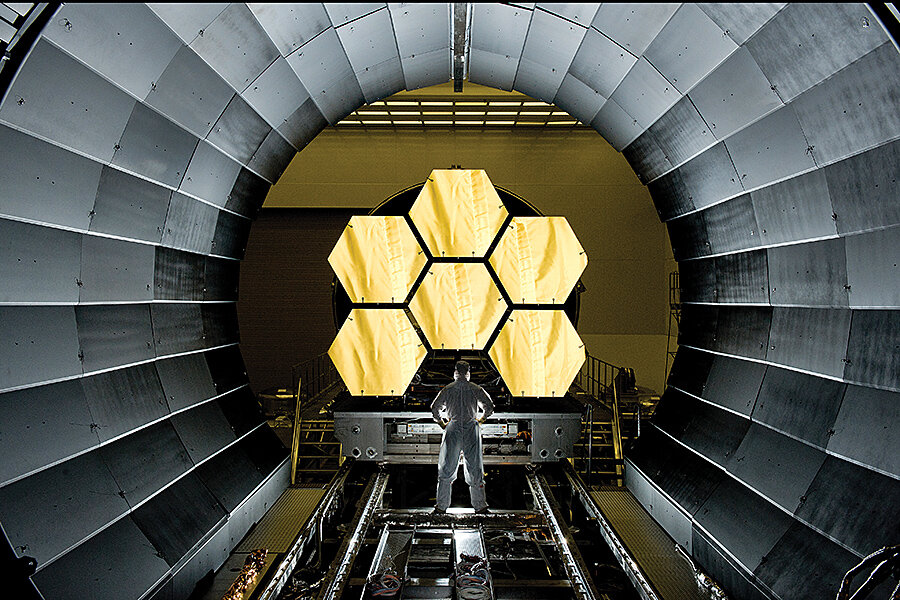

Over the next generation, the James Webb Space Telescope, which is scheduled to launch in 2018, will peer even deeper into the universe. Along with the durable Hubble, it will probe the formation of galaxies, study planets around distant stars, and shed more light on the origin of life. Back home, scientists will work to make sense of what our starry messengers are seeing, and humans undoubtedly will be required to shift their thinking about the cosmos again and again – sometimes reluctantly but usually with the same wondering delight Galileo felt.

John Yemma can be reached at yemma@csmonitor.com.