A heart that refuses to close

How long does forgiveness take?

That was the question Giselle Mörch asked. She had just heard the story of a man whose brother had been murdered in an argument over sneakers. The man’s forgiveness was instrumental in getting his brother’s murderer released on parole. Now, he works with his brother’s killer to promote reconciliation and healing in communities.

But he had no answer for Ms. Mörch. “On your journey to healing, you may not even get to forgiveness, but you don’t have to put any parameters around how long it’s supposed to take.”

It was an answer Mörch could understand.

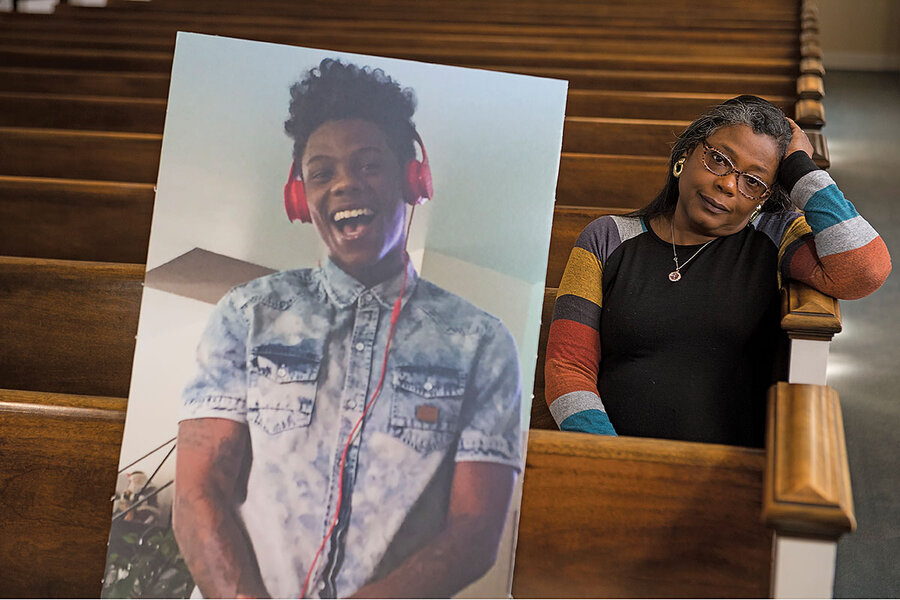

Staff writer Harry Bruinius’s cover story this week is an extraordinary look at the graces and trials of the attempt to forgive. It charts the stories of two mothers, Mörch and Jolyn Hopson, whose lives intertwined in the most searing way: Ms. Hopson’s son, along with two others, is charged with killing Mörch’s son.

What emerges is a portrait of striking intimacy – a product of the trust these women put in Harry to tell their story honestly and compassionately. And in its own way, the story offers an answer to Mörch’s question.

It tells of Hopson, who lost 50 pounds as she wrestled with her own intense emotions and woke up every morning at 6 to pray for Mörch – before she even knew her. It tells of Alice Oaks, who found the strength to forgive after her first son was murdered but is “praying to God to keep strengthening me to press forward” after the murder of her second son. And it tells of Darryl Green, who works alongside his brother’s murderer in a venture called Deep Forgiveness.

“How many of you feel like you are dying inside?” he asked a group including Mörch at one session. “How many of you are carrying this huge weight around?”

“Sometimes it is a spirit of unforgiveness that will kill you.”

For some, like Mr. Green, forgiveness takes time. In his case, it took 20 years. And he still thinks about the fact that his brother will never get to meet his nieces. “Not every day is a good day.”

For others, like Mörch, forgiveness for all those involved in a loved one’s death seems a task of such enormity that it is beyond words. Considering it, she can only utter an awestruck “wow.”

What binds them, however, is the struggle to embrace the forgiveness that has kindled even when it is not yet complete or comfortable. Mörch hopes she can work with Hopson to help local youths. She has, she says, taken a “baby step.”

And what brings them together is the mutual bond they form. Mörch’s story is a window into how communities beset by violence begin to cope with the unthinkable toll: by leaning on one another.

How long does forgiveness take?

Harry’s story suggests that this may not be the right question. Perhaps more important is the beauty of a heart that refuses to close, despite the deepest wounds the world can make.