From ‘Children in darkness’ to a generation of light

Loading...

Early in my career at the Monitor, I worked on a series called "Children in darkness: The exploitation of innocence." Our assignment: document the lives of children who had been forced into prostitution, combat, and labor around the world.

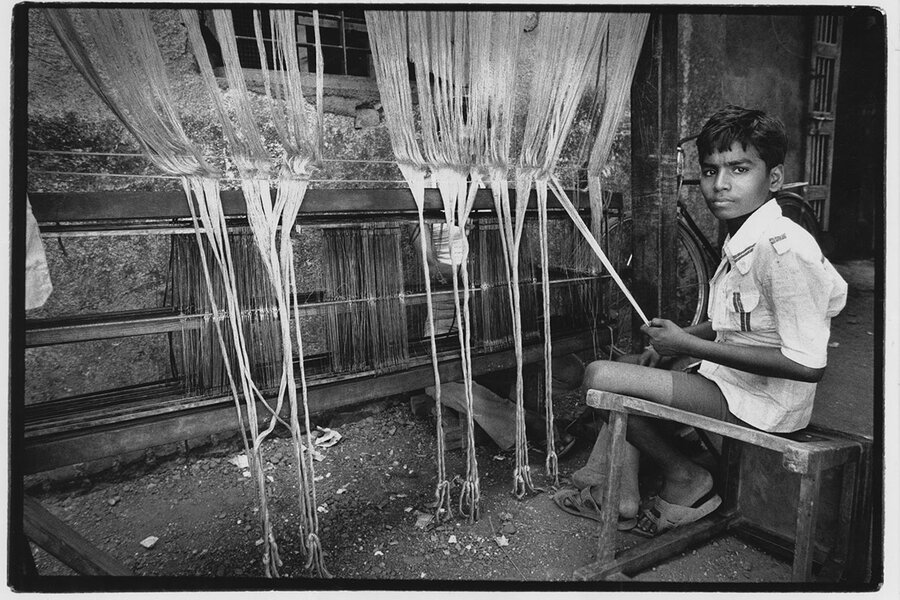

In Peru, we traveled for miles in a tippy, dug-out canoe to find children toiling in gold mines on riverbanks. In Kashmir, we encountered children laboring all day in carpet factories – their small hands and nimble fingers able to make the tiny knots needed to produce the most valuable rugs. In Manila, Philippines, we met 9-year-old Ray, who had been forced to sell his body for sex at the height of the AIDS crisis. And in Baghdad, during the Iran-Iraq War, we came face to face with Iranian teenagers who had been held captive and used as human minesweepers in front of older Iranian troops.

I was a young photojournalist on one of my first assignments in the developing world, so it was a lot to take in. I was used to photographing happy kids on playgrounds and in schools, lovingly shepherded by doting parents and teachers. But poverty and war had created a different reality for youths elsewhere.

I will never forget their eyes, pleading, but also proud and defiant.

I'm often asked, how do you do it? How do you confront this sort of misery? I guess my camera is a kind of buffer – at least while I'm actively taking the pictures. Back in the late 1980s, I was shooting black-and-white film, which needed to be developed and then printed. There was a lag until I saw my work again. When the images appeared in the darkroom, I experienced the reality of what I had witnessed all over again. To be honest, I couldn't do what I do if "we," the Monitor, didn’t look for solutions to the world’s problems.

I'm looking back at those black-and-white photographs because that series inspired my colleague Sara Miller Llana (later joined by Stephanie Hanes) to investigate how young people are faring today. It quickly became evident that the big issue facing them – and all of us – is climate change. But this time we didn't find victims; we found innovators. In Namibia, one of the driest countries in the world, and in Bangladesh, one of the wettest, we found youth activists who impressed me with their eloquence and a maturity beyond their years.

In this issue, you'll find the last of our seven cover stories about what we're calling the Climate Generation. Sara and I met with young people in Arctic Canada, who are embracing traditional ways as taught by their elders. Together they are learning how to use modern technology to measure changes in their environment so that scientists and policymakers can use the data to act.

Today I work with digital cameras – so I can view my images immediately on my camera's back screen. I see something wonderful in the climate activists we profiled: ingenuity, energy, imagination, creativity, agency.

And, best of all, their eyes are filled with hope.