'Tiger Mother' isn't about parenting. It's about declining American exceptionalism.

| Virginia Beach, Va.

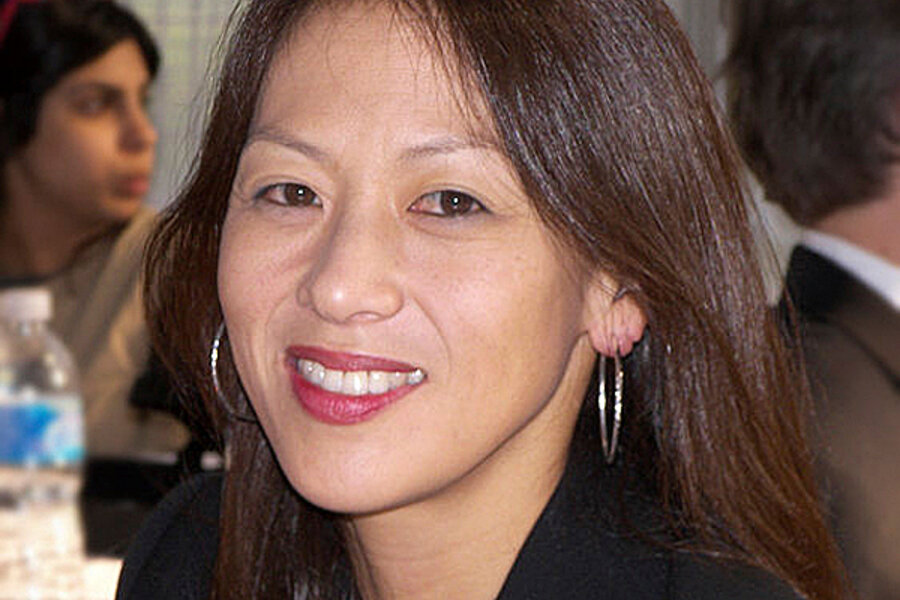

By now, everyone has heard about Yale law professor Amy Chua’s new book about Asian parenting, Battle Hymn of the Tiger Mother. The book has been hotly debated in news reports, on-line, and in neighborhoods and PTA meetings across America. But I’d like to suggest that Ms. Chua’s book is actually not about parenting at all. It’s about something much deeper than that.

As a political analyst, I was struck by two ideas which appear to underlay Chua’s analysis of the world: 1) the notion that there is no such thing as “giftedness”; there is merely hard work, and 2) the notion that the “third generation” is the one headed for trouble. These two statements are problematic for Americans, since they have implications for our own position in the international system as well.

In the international system, America has always behaved like a gifted child. Here, the child labeled gifted is defined as uniquely endowed with special abilities. He is intrinsically motivated and equipped with the potential for high level achievement. Similarly, the rhetoric of American exceptionalism explains the “miracle” of America’s rise to power with reference to America’s superior genetic endowment. America is described as “blessed” with a huge land mass, natural resources, good harbors, and citizens who are uniquely hard-working.

RELATED: Shanghai test scores have everyone asking: How did students do it?

But where Western educators embrace giftedness, Asian educators stress hard work and determination. Analysts who describe the rise of the Asian tiger economies do not stress unique endowments or gifts but rather hard work, rational strategy, and the willingness to forgo short-term gratification to achieve goals.

What happens next for America?

Here, it appears that both types of strategies can produce success. But the more interesting question Chua’s book raises is this: What happens next? The danger for the gifted child (or nation) is that at some point, raw talent and luck will not be enough to carry him forever. For the diligent student (or nation), the danger is that hard work is not enough to reach the next level. Here analysts argue that China’s draconian childrearing methods leave their students (and their nation) ill-equipped in the areas of creative thinking and problem-solving.

In her memoir, Chua describes three generations of Asian families: The first generation works and sacrifices, and the second generation works hard, buoyed by the advantages bequeathed them by previous generations. The third generation, however, risks losing that drive and becoming soft.

Although Chua never uses the term, the phenomenon she describes in her work is the same one noted by the political scientist Ronald Inglehart in the 1970’s. He argued that it was possible for an individual in the developed world to feel content and secure enough to be willing to give up authoritarianism and an emphasis on social order in order to pursue other types of freedoms, including a drive for meaning and self-expression.

Do we need to work harder like the Chinese?

Thus, Chua finds herself stymied by the question: What does it mean to give a child a “better life?” She supports routines, strong family structures, and respect for the past, but finds her children craving autonomy and self-expression. Here Chua asks: Must all Americans end up capitulating to grand social forces and decide to go easy on their children, valuing free expression over order and discipline?

Chua’s dilemma is the same one which America itself faces today. Do we want to be more like hard-working China or more like the free-wheeling, self-actualized Europeans? Particularly today, it sometimes seems that free expression and self-fulfillment have gone too far in America. News stories describe the rise of hate speech, an irresponsible media, and candidates who don’t respect the political system or their elder statesmen. America seems characterized by generational warfare, class tensions, and anti-immigrant sentiments. In short, America seems to be becoming more like Europe.

Study in America: Top 5 countries sending students to US

The question then becomes whether discipline and the restoration of order are the only possible solution to the growing pains that America seems to be experiencing. Would embracing Chinese parenting and Chinese values thus be a step toward the future or a step toward the past?

Mary Manjikian is assistant professor of international relations at the Robertson School of Government, Regent University, and holds degrees from The University of Michigan (MA, PhD), Oxford University (M.Phil). She is the author of the coming book “The Romance of the End: Americans Imagining Apocalypse and its Implications for International Relations Theory.” She is a former US Foreign Service officer.