The Geneva Accord: a breakthrough model

Loading...

| Tel Aviv

Just over a decade ago, Israelis and Palestinians met at Camp David. The weeks leading to the summit were full of expectation. There was a sense that an agreement was within reach. It was the last summer of the Clinton administration, and everyone thought that the president of the United States would not convene a summit that would lead to anything short of a historic triumph. So determined, it seemed, was everyone to succeed, that success almost seemed predetermined. And indeed, some even believed that an agreement had already been secretly reached – that it was a done deal. Peace, it seemed, was at hand.

But this, as it turned out, was not the case. Instead, the Camp David summit of July 2000 came to be one of the most tragic milestones of the peace process between Israel and the Palestinians. It was a particularly ironic tragedy, for the gap between expectations and results could not have been greater.

The reasons for the summit's failure are complex and will probably remain in dispute. But the failure was real and the frustration was felt by everyone. It was felt particularly acutely by those of us members of the negotiating teams at Camp David and the too-brief round of talks that followed at Taba, Egypt.

Particularly frustrating was an emerging narrative that saw our failure as a sign that the very conflict was insoluble. Someone had to prove that this was not the case. And so, in a meeting with Palestine Liberation Organization Executive Committee member Yasser Abed Rabbo, I suggested that we continue the work that was interrupted in Taba until we could conclude an agreement. Frustrated as we were, we were determined to demonstrate to both Israelis and Palestinians that despite the disappointment, despite the violence, peace was possible.

Our work was not easy – not only because of the essence of what we had set out to do, but also because of the conditions under which we worked. The violence that erupted in the wake of the failed Camp David summit led to roadblocks and closures and restrictions on travel that made a meeting itself nearly impossible. Sometimes we had to meet abroad because meeting at home was not possible. Other times we could only meet at a checkpoint and hold our discussions in a car. The contrast between the backdrop to our work (violence and crisis) and the center of our work (a comprehensive permanent-status peace agreement) could not have been greater.

To support our effort, we built broad coalitions. On the Israeli side, we brought in a number of individuals from the heart of the establishment, including former senior military officers. On the Palestinian side we brought in officials from Fatah, parliamentarians, and leading academics. In 2003, after almost three years of hard work, our negotiating teams concluded the detailed draft agreement that has since been named the Geneva Initiative.

How the agreement works

Our proposal details what a credible, negotiated Israeli-Palestinian peace agreement could look like. It addresses all the major issues between the parties, including security arrangements, the status of Jerusalem, access to holy places, and a just and agreed-upon solution to the problem of refugees.

And, of course, it addresses the contours of permanent borders and the future of West Bank settlements. In this, it draws heavily on the ideas presented to us by President Clinton. With pre-1967 lines (the Green Line) as our starting point, we devised a series of agreed-upon, minor land swaps on a reciprocal, one-to-one basis, according to a formula that would require Israel to evacuate the smallest number of settlements while granting Palestinians the greatest part of the land.

The result is a model that would create a Palestinian state on nearly 98 percent of the West Bank and the Gaza Strip, with the shortfall compensated for by territories inside the Green Line. The borders we drew would allow the vast majority of the settler population (75 percent) to remain in territory that could come under Israeli sovereignty.

Implementation of the plan would take place gradually over 30 months, in accordance with the detailed timetable set out in the Annexes to the Geneva Accord, which were produced under the collaboration of our Israeli and Palestinian teams and published in 2009.

The key to our success in reaching a comprehensive agreement was not in the specific solution we offered to each issue – although there was also a lot of creative thinking there, too – but rather in the concurrence of the solutions we offered.

Comprehensive and conclusive

That is to say, borders and settlements are not simply inter-related with one another alone, but with each of the other final-status issues – most notably those with the greatest symbolic significance: refugees and Jerusalem. We could not reach an agreement without understanding them as such. After all, the question of borders pertains to the area of Jerusalem as well. And as often happens in negotiations, a concession by one side on one issue often allowed a breakthrough in another. In short, we drafted an "accord" that, true to its name, became an accord not only between the two parties but also resolved all the outstanding issues between the two sides. It was comprehensive and conclusive.

As such, it has drawn the support of majorities in both societies. According to the most recent polling data, solid majorities in both societies support a comprehensive, negotiated final-status agreement based on the parameters outlined in the Geneva Accords. These numbers reflect support for the total package that is higher than support for several of its individual elements.

What now? In December, speaking to a delegation of senior Israelis in Ramallah, West Bank, at an event organized by the Geneva Initiative, Palestinian Authority President Mahmoud Abbas suggested that "[Once we] resolve the issue of borders, it will be possible to also resolve all the others." It is fortunate, then, that a mutually agreeable formula already exists.

My colleagues and I – both Israeli and Palestinian – have pledged to work together and within our respective communities to turn Geneva into reality. We hope that people of goodwill around the world will join us in our pursuit of a just and lasting peace between our two peoples, so that we may live side by side in freedom and security as equal neighbors.

Yossi Beilin is a former member of the Knesset and former minister in the Israeli government. A veteran Israeli negotiator, he launched the Geneva Initiative with Yasser Abed Rabbo in 2003, presenting a full model agreement between Israel and the Palestinians. He is the author of several books, including "Israel: A Concise Political History" and "Touching Peace."

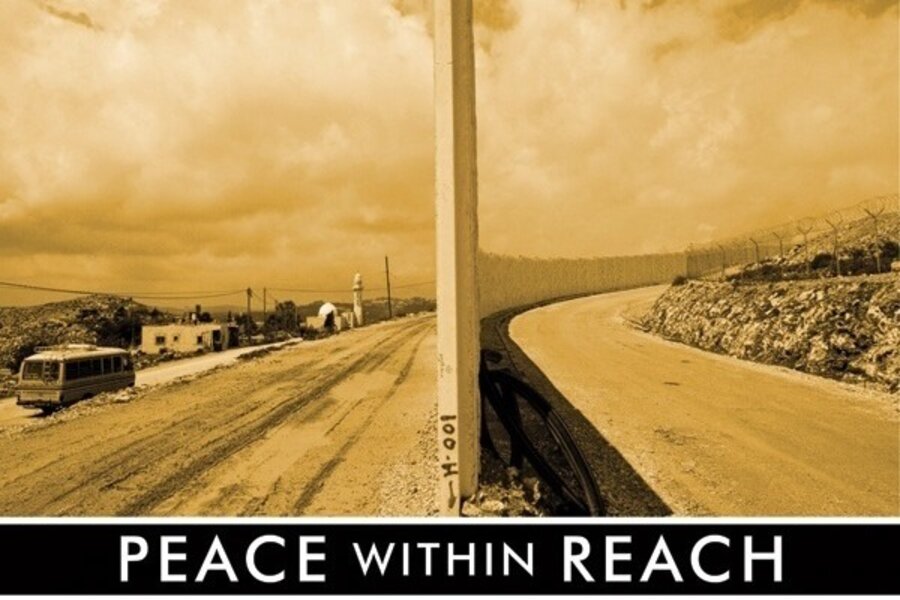

Editor's note: This is the second essay of "Peace within Reach," a three-part commentary series about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

No. 1 - For Arab and Jew, a new beginning

No. 3 - A holy city's peaceful purpose