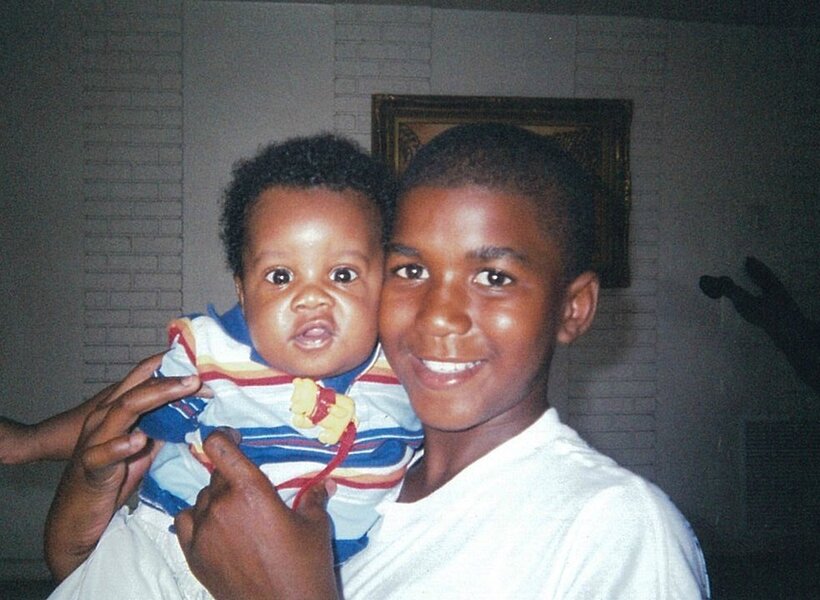

Trayvon Martin could have been my brother

Loading...

| Boston

Trayvon Martin could have been one of my younger brothers. I think about their caramel and mocha skin tones, wardrobes full of hoodies, and frequent trips to the corner stores. One of them was once stopped by the police, frisked, and told he fit the description of someone dangerous. My brother is not a criminal.

I hurt every time I log on to Twitter or Facebook and see hundreds of familiar and unfamiliar faces dressed in hoodies in support of Trayvon Martin.

This killing in Sanford, Fla., was tragic. A 17-year-old African American, on his way home from the store armed with nothing more than a bag of Skittles candy and iced tea, shot by a neighborhood watch captain named George Zimmerman, who followed Trayvon even after police told him not to.

This young man wasn’t given a fighting chance in life, but after his death, he has millions of people fighting for him. Along with his parents, lawyers, and civil rights leaders, the social media community is gathering and asking piercing questions.

I’ve read questions like these:

Why would a grown man carrying a firearm feel threatened by a 140-pound teenager?

Why did George Zimmerman shoot Trayvon when he was only carrying candy and a drink?

Is Trayvon’s killing a form of modern-day lynching?

Why did Trayvon’s family have to file a “missing person” report to find out he was in a morgue?

Why is Trayvon’s killer free? Where’s the justice?

Social media has provided a digital meetinghouse for millions to join globally. It has given concerned citizens a space to voice their opinions about the injustices in their countries and to lobby others to support a cause that wouldn’t have received such attention without the masses behind it.

I recently read a tweet that stated, “If people feel like ‘Twitter Activism’ doesn’t matter, ask Egypt, Tunisia, and Iran.”

Like the Arab Spring and Occupy Wall Street movement, Trayvon’s story has sparked several rallies and protests around the nation. Videos titled #MillionHoodies have gone viral on Twitter, prompting a Million Hoodie March in New York City on Wednesday.

As a journalist, it’s second nature for me to be immersed in news, but for my 10-year-old brother, YouTube and Facebook are his news sources. And that, also, worries me.

Social media may be easily accessible and connecting, but we must be careful about its trustworthiness. Facts can be misconstrued, wrong, or just plain missing.

I learned an essential lesson about this after speaking to several Ugandans – via social media and at a local restaurant – about the recent Kony 2012 campaign. They said that the subject of the video, the violent warlord Joseph Kony, was a man of the past and no longer attacking northern Uganda (though he is at large and operating elsewhere in Africa).

As time passes, we learn more about Trayvon’s case. For instance, he was shot in a neighborhood that had experienced several break-ins in the last year. He was walking in the rain in a community where his killer assumed he didn’t belong. On the other hand, there’s this business about Mr. Zimmerman’s possible racial epithet caught on the 911 recording of the incident.

Even absent more facts, though, it’s fair to ask, was Trayvon typecast?

Americans need to think about the implications of this case, in their own experience and as it applies to the law.

And my brothers need to think about it, too. As they tweet away in their hoodies and share their thoughts on their Facebook walls, I encourage them to use their tweets and posts wisely. I want my siblings to be proud of who they are on and off the web. They should feel safe walking down a street in Boston or Sanford, free from fear or misjudgment.

As I wait to see what happens in the Trayvon Martin case, I can only hope that the Martin family and social media activists get the justice they are fighting for. And that my brothers might be just a bit more safe the next time they’re on their way to the store.

Nakia Hill is a journalism graduate student at Emerson College in Boston and an intern on the commentary desk at The Christian Science Monitor.