Defenders of the 'Chinese way' are off the mark

| Ithaca, N.Y.

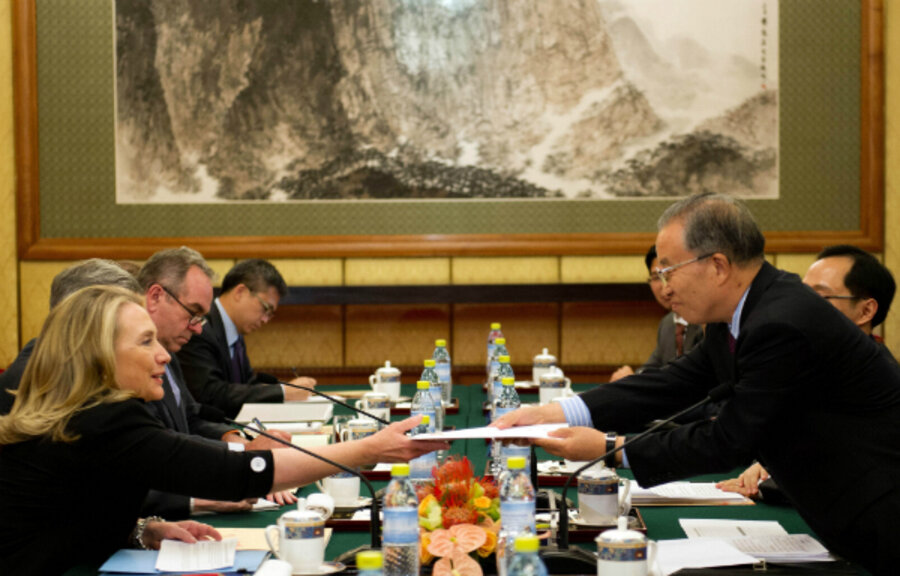

Hillary Rodham Clinton is in China again, this time trying to nudge Beijing toward a collaborative, multinational solution to its many territorial disputes with its neighbors. But predictably, the Chinese government is claiming its unique status to do things its way, with a foreign ministry spokesman saying China has the “obligation to safeguard its territories” and an editorial in The China Daily proposing an “Asian” approach to the issue.

Secretary of State Clinton last visited China in May, as a blind Chinese activist, Chen Guangcheng, sought refuge in the American Embassy from years of state persecution. Then, visiting Mongolia in July, she denounced countries that imprison dissidents and deny citizens the right to freely choose their leaders.

Her insistence on a democratic approach to controversies in the region has brought out similarly insistent statements from defenders of the “Chinese way.” In the op-ed sections of The New York Times, The Christian Science Monitor, and elsewhere in the American media, these defenses point to the flaws of democracy while touting China’s special Confucian-communist meritocracy or Confucian culture and history, all the while heralding the legitimacy and popularity of the current regime as the natural choice for China.

Such ideas are part of a much larger discussion of “Chinese characteristics” in recent decades. Promoted by the state and state-friendly intellectuals, the notion of Chinese characteristics portrays the people of China as so unique, on account of their longstanding cultural traditions, as to be immune to the political and cultural change that has swept the world in recent decades. And while supposedly determining China’s sole proper path for handling any and all issues, these unique characteristics, according to their proponents, remain conveniently unable to be fully grasped by outsiders.

Whether applied domestically or internationally, this is a harmful line of thinking.

The primary political effect of these ideas is to deny the inevitable trend of democratization in recent decades – in Asia, Latin America, Europe, and Arab countries. Ironically, however, the notion of Chinese characteristics appeals to many of those whom it would deceive and ultimately disenfranchise. Internationally, it rationalizes authoritarianism under the guise of cultural sensitivity to a uniquely Chinese way. Domestically, it fulfills a desire for uniqueness and exceptionalism in order to distract citizens from the growing desire for basic political and human rights.

Let’s look at one particular political proposal by China scholars Jiang Qing and Daniel A. Bell in The New York Times in July. Critical of democracy as a solution to China’s political and social malaise, the authors instead seek a political framework based in “the longstanding Confucian tradition of ‘humane authority.’ ”

This abstract ideal is embodied in a proposed tricameral legislature featuring: (1) a House of the Nation whose members are descendants of Confucius and other sages, (2) a House of the People whose delegates are “elected either by popular vote or as heads of occupational groups,” and (3) a House of Exemplary Persons populated by scholars of the Confucian classics, armed with final veto power on all legislation.

This elaborate framework, seemingly based in millennia of tradition, is in fact a mystifying rationalization of authoritarianism under the guise of cultural sensitivity. The writers argue that framing the debate in terms of authoritarianism vs. democracy is restrictive and does not leave room for local traditions. But they overlook the fact that far more burdensome restrictions are apparent in their counter-proposal.

The notion that China’s future must inevitably be found in its past, after all, is not particularly liberating, especially when one considers that this past represents a period prior to accountability in governance and recognition of human rights. Anyone who proposed a similar framework for the future of a western country, or even for such traditionally Confucian – but democratic – neighbors of China as South Korea, Japan, or Taiwan, would not be taken seriously.

Equally restrictive is the quirky proposal that the House of the Nation be populated by direct descendants of Confucius and other sages. One such male-line descendant is Kong Qingdong, a professor at Peking University and a contentious Chinese pop-culture figure. Besides his ancestry, which he never hesitates to cite, Prof. Kong is best known for his outspoken hatred of “traitorous” liberals, his fondness for the North Korean political model, and his recent characterization of the people of Hong Kong as “dogs” and worse. Clearly, cultural sensitivity is not a two-way street.

The cultural sensitivity to which a Confucian constitution and other similar proposals appeal is based in a sense of exceptionalism, suggesting that a uniquely Chinese path is necessary, and that any critique of such a path is inherently offensive.

Yet culture is an intangible idea which those in power can far too easily misuse as a cover for offensive practices. We see that now as Beijing uses its "values" to restrict the Internet, for instance. We see it in Iran, which legitimizes the suppression of women and the persecution of homosexuals on account of "historical, cultural, and religious backgrounds."

Sensitivity to another culture can only be justifiably premised on that culture’s sensitivity toward its own people. When culture is cited as an excuse to rationalize authoritarianism, to crush reasonable dialogue, or to deny people fundamental political or human rights, this “culture” is not worthy of sensitivity.

While open debate about the issues facing China is essential, the invocation of a uniquely “Chinese way” as the final arbiter of political correctness seems far more likely to stifle rather than encourage debate. Seeking solutions for the future in the past is primarily a distraction from the real issues of the present, as well as real solutions.

Kevin Carrico is a PhD. candidate in sociocultural anthropology at Cornell University, researching neo-traditionalism, nationalism, and ethnic relations in contemporary China.