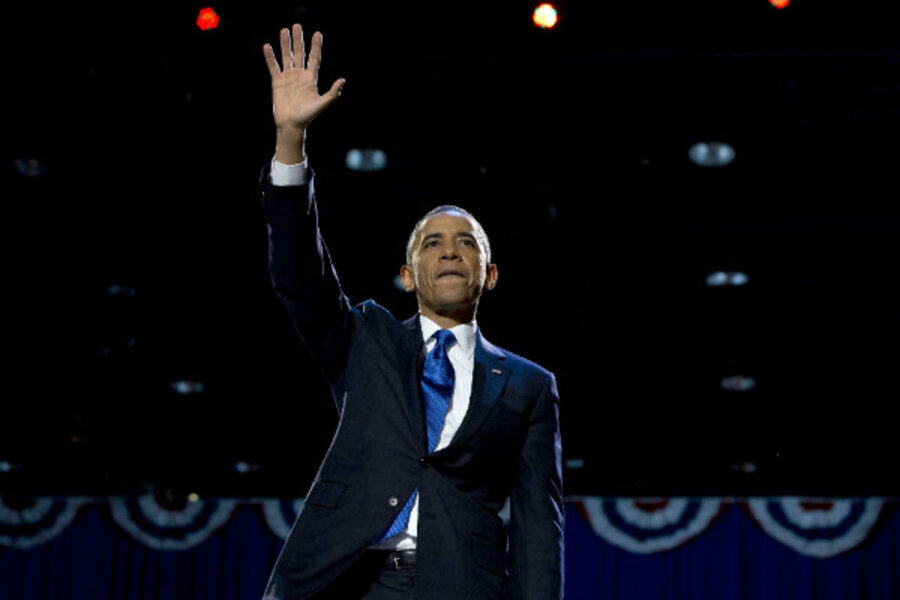

Exit polls show President Obama should go on listening tour, not take victory lap

Loading...

| Wheaton, Ill.

Plenty of ink will be spilled chastising Republicans and the Mitt Romney campaign for their many missteps and missed opportunities. But they aren’t the only ones who were tone deaf in Election 2012.

After the costliest campaign in American history, spending $1 billion to squeak out a win against a candidate more than half of the voters disliked, President Obama becomes the first president since 1832 to win a second term with a smaller percentage of votes than in his initial victory.

Instead of running victory laps, Mr. Obama should go on a listening tour.

Exit polls confirm what the small margin of victory suggests: Voters are ambivalent about the president and his record. Tuesday’s vote was not a resounding affirmation of the past four years; it was a stark reminder that the nation is deeply divided. The president needs to listen to the echoes from the exit polls, broaden his approach, and seek a new direction for his second term.

A majority of voters say that things in this country today are “seriously off on the wrong track.” A super-majority rate the state of the economy as not so good or poor.

Voters split evenly – 49 percent to 49 percent – in their feelings of relative satisfaction with the Obama administration. At the extremes, only 25 percent of voters are enthusiastic about the administration, and 19 percent are angry.

Even more telling, 46 percent of voters have an unfavorable view of the president. In a typical election, an unfavorable rating above 40 percent is seen as a death knell for incumbents. Obama’s saving grace was that voters disliked Mr. Romney even more.

Obama’s signature legislative achievement of his first term, health-care reform, drew very mixed reviews. Forty-nine percent of voters favor repealing all or most of it, 44 percent say to leave it as it is or expand it, and many of the controversial aspects of the legislation have yet to go into effect.

When asked which candidate would best handle three particular issues, Romney edged out Obama on the economy and the federal budget deficit, and a slim majority said Obama would better handle Medicare.

Last-minute voters broke in favor of the president, who won the 9 percent of the voters who decided in the last few days. Indeed, the October surprise of superstorm Sandy and its made-for-TV presidential photo opportunities likely stopped Romney’s momentum and tipped the election for Obama. (The 42 percent of voters who said that hurricane Sandy was an important factor in their vote chose the president by a 37-point margin.)

Both parties won resounding support from their base. Independents chose Romney by a five-point margin, but the Democratic edge in total voters pushed the final tally toward Obama.

Bill Clinton pleaded with the American people to give their president four more years to finish the job, and by a slim margin they consented. Obama should seek the counsel of his party’s elder statesman once again. Mr. Clinton learned from the 1994 Republican wave in Congress, changed his tactics, and worked with Republicans to balance the budget and enact historic welfare reform.

Obama would do well to follow in Clinton’s footsteps by bridging partisan chasms before his party faces the voters again in 2014. Of course, Republican leaders in the House also have to be willing to come to the table, ready and willing to negotiate in good faith.

But Obama’s small margin of victory is no mandate for staying the course. Voters are frustrated with both parties digging in their heels and refusing to work together. Obama needs to read the exit-poll tea leaves, demonstrate more political flexibility and willingness to work in coalitions, and champion real solutions to the vexing problems facing our country.

A humbled president who seeks partnerships across the aisle and is willing to listen to and engage the concerns of groups outside his liberal base – that would be real change that America could believe in.

Amy E. Black is associate professor of political science and chair of the department of politics and international relations at Wheaton College in Wheaton, Ill.