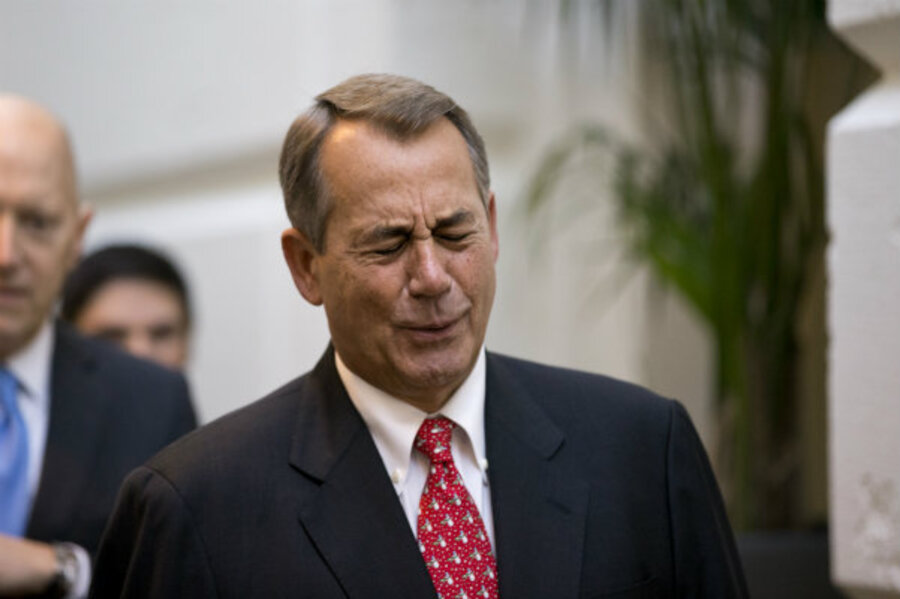

Will John Boehner, President Obama master art of humility before 'fiscal cliff'?

Loading...

| Houston

John Boehner and President Obama continue their tussle over tax increases and spending cuts that would be part of budget deal to avoid the fiscal cliff. Neither Democrats nor Republicans are eager to concede ground, lose face, or give up what their parties stand for. To some extent, each side has a vested interest in protecting their position, as doing otherwise means they could lose the support of voters, prominent positions within their party, or financial backing.

Beyond politics, each of our officials generally has a committed view of what’s right, just like most of us. What we all need is a healthy dose of humility. The general public, opinionmakers, and elected leaders need to realize that they’re not as right as they think they are, and they need the other side to help show them where the weakness in their view lies. Those who were responsible for founding the nation and its early success knew this lesson well. We should look to them for guidance.

One of the most divisive issues early in our nation’s history was the national bank. Championed by the first Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton, the debate over the national bank divided George Washington’s administration. Hamilton was on one side, while Washington’s Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson, and his ally in Congress, James Madison, led the opposition. In 1791, the first national bank was established, and the first party system began to take shape, with Jefferson and Madison going one direction and Washington and Hamilton going the other.

Madison was elected president just as the 20-year charter for the national bank was set to expire. This was his chance to end what he thought was a destructive and unconstitutional institution. But war with Britain was imminent, and his treasury secretary advised him to reauthorize the bank so the US could finance the war. In 1814, Congress passed a bill chartering the second national bank, and Madison vetoed it. But when Congress tried again in 1816, Madison signed it. Madison justified the change of heart by saying that the bank was what the nation needed. He acknowledged that his opinion was against the majority of the nation’s and he had no right to violate the will of the voters and their representatives in Congress.

That is humility.

Looking to another Founding Father, Benjamin Franklin shows us how we can act, if not become, humble.

By changing his manner of speech, Franklin was able to demonstrate how humility makes one more sociable, even if that humility is only superficial. For instance, Franklin found that when he positioned his argument in more conditional terms, rather than being assertive and inflexible, he was able to interact in a more positive way. By Franklin’s own account, he was outwardly humble because he found that people were more receptive to his arguments when he used phrases that connote humility such as “it appears as if” or “perhaps we can say,” rather than positive assertions that connote pride such as “it certainly is” or “it is undeniably so.”

By speaking humbly he not only became more agreeable, he also became far more persuasive.

Changing one’s manner of speech is one thing – a kind of first step in the path toward humility. But recognizing that one’s cognitive capacities are limited and one’s views may be fallible is a step most don’t take. It is the step lawmakers must now take, however, following in the footsteps of Madison. With humility, reconciliation could be possible, even over the most divisive matters.

Kyle Scott teaches American politics and constitutional law at the University of Houston. His commentary on current events has appeared many national and local media outlets.