Kabila has overstayed his welcome

The fourth-largest African country (by population) possesses vast deposits of mineral wealth, from cobalt and copper to diamonds and gold. Yet it suffers from two familiar troubles that have vexed countries on that continent in recent decades: It has a large proportion of its people who live in extreme poverty and a political leader who refuses to leave power.

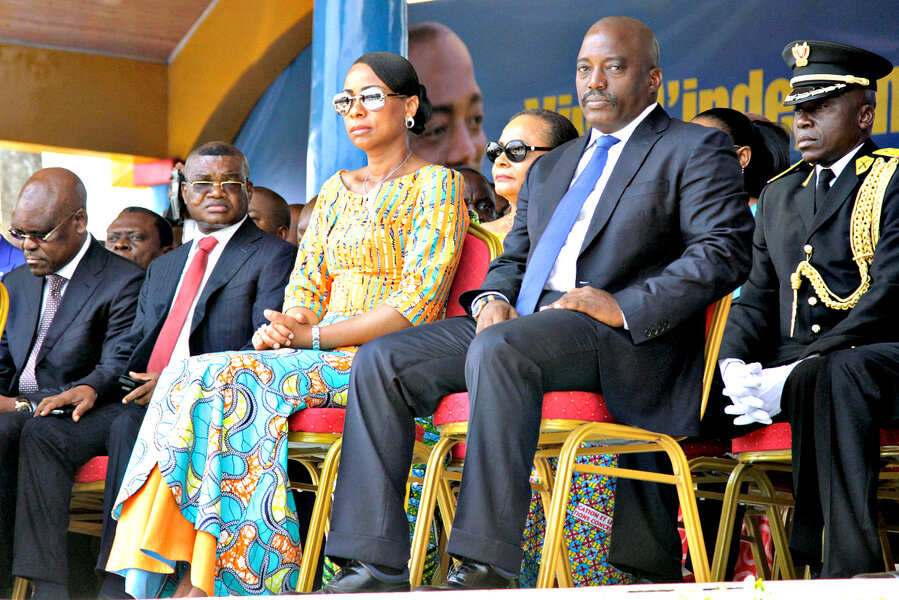

Joseph Kabila has served two terms as president of the Democratic Republic of Congo, the limit under that country’s constitution. Yet when his term of office officially ended Dec. 19 he was still in the executive’s chair, arguing that the nation was not yet prepared to hold an election.

He has offered to conduct an election in 2018, but opponents say that isn’t good enough – not just because it flouts the constitution but because they suspect he will use the intervening time to change the law to allow himself a third term.

In September some 50 people protesting that elections be held on schedule were killed. Another 40 protesters have been killed within the past week. A compromise being bartered by the Roman Catholic church in the Congo, a nation of some 80 million people, is being hastily negotiated this week.

Mr. Kabila has served as president ever since his father, Laurent-Désiré Kabila, who served as president from 1997 to 2001, was assassinated. One poll has found that only about 8 percent of Congolese say they’d vote for Joseph Kabila if an election were held now.

Investigations have shown troubling ties between the president and a vast array of businesses owned by his family members. The president’s siblings are involved in at least 70 businesses across the country, according to an investigation by Bloomberg News. The Kabilas’ sprawling network has put hundreds of millions of dollars in the pockets of family members. Besides mining interests they include banks, farms, hotels, and nightclubs.

The concern that the legitimacy of these business ties to the president might come under scrutiny when a new government takes office may be one of the strongest reasons why Kabila is refusing to leave.

In April US Secretary of State John Kerry met with Kabila and urged him to hold timely and credible elections. And more recently the US and the European Union froze the assets of, and banned travel by, nine senior members of Kabila’s government who are thought to have played a role in repressing dissent in recent years.

Whether Kabila is listening to either outside governments or his own people remains to be seen. He may struggle awhile longer looking for a way to keep the status quo.

But the sooner he voluntarily leaves office, as the constitution demands, the less likely it is that a succeeding government may take severe action against him.