A grass-roots model to counter words that incite

Loading...

When President Trump used words of violence – “fire and fury the world has never seen” – to threaten North Korea, many people rushed to calm fears that his nuclear rhetoric might become a nuclear reality. Journalists asked experts to assess the risk of war (and found little). China called for more diplomacy. Even Mr. Trump’s own secretary of State, Rex Tillerson, assured Americans that they “should sleep well at night” despite North Korea’s own threats and those of the US president.

In a world in which words that might incite violence can travel at the speed of a tweet, the need for calming voices is even greater than in the past. Facts must be checked quickly. Historical context must be provided. Adversaries who spout hate should be encouraged to find common ground. The social order that favors tranquility and the primacy of good must be asserted.

Such voices often need to be quick to respond. If someone stands up in a crowded movie house and yells “Fire!” when there is no fire – an illegal provocation in many countries – others must be ready to prevent a stampede to the exits. People of authority, such as police and schoolteachers, are taught to be alert for incendiary words and how to defuse a verbal altercation. Yet that responsibility of appeasing angry adversaries can fall on anybody, with words of violence often flying fast these days between smartphones or over satellite TV.

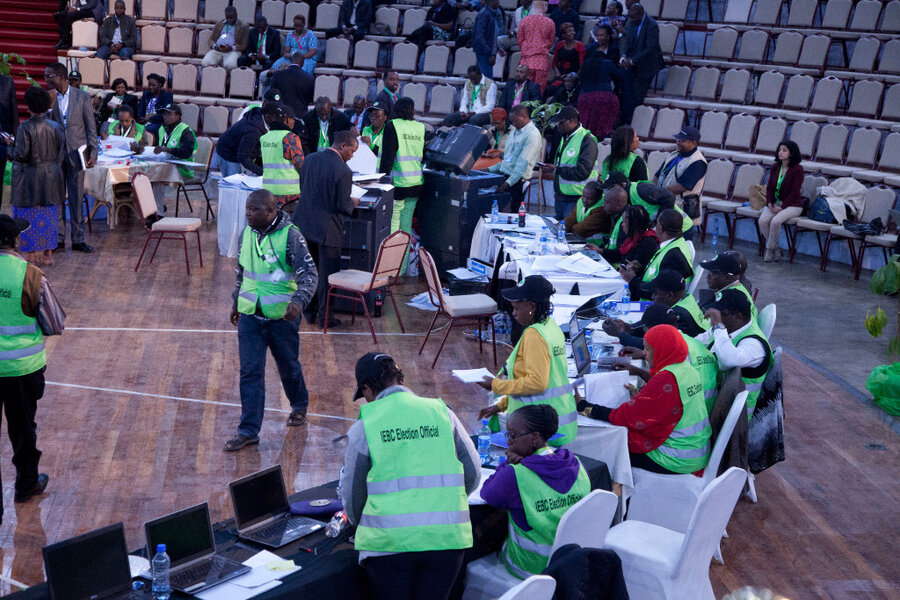

In Kenya, which held a tense election on Aug. 8, a novel experiment is under way to teach local people how to prevent postelection violence, especially when social media has become so pervasive.

After a close election in 2007, the African country saw more than 1,000 people killed when politicians incited crowds to take revenge on political opponents. Civic activists had to learn hard lessons. As Adams Oloo of the University of Nairobi writes in a new book: “Kenya has witnessed the rise of noninstitutionalized networks of groups and individuals that are struggling to expand understandings of politics and bring about social change in terms of behavior, relationships, and ideas.”

For this election, soldiers were certainly better ready to prevent violent protests. But perhaps just as effective is a new network of peace activists who are being proactive. With international support, they have identified hot spots where violence might occur and identified local people held in high regard (“influencers”) to be ready to respond by phone, text, and social media to fake news, rumors, and hateful language. A team of some 2,000 has been trained in mediation to deal with local disputes related to the election.

Many of these first-responders were able to resolve conflicts before the voting. Now with the public receiving vote tallies for candidates, these peacemakers remain on the job. They check facts, provide context, and act quickly to initiate dialogue. If they succeed, they could be a model for common people everywhere to counter words that incite violence – with actions that heal.