A prize for dwellings that connect

Loading...

When architects are asked to design a community from scratch, many start from the premise of a shortage in basic housing. In the United States, for example, the number of people seeking to rent has been at record highs for five years. Yet construction of new units is about a third below demand. The result: Of the 44 million Americans who rent, about half spend more than 30 percent of their income on housing.

The easy solution is more high-rises, right?

Not necessarily, according to a breed of architects who start from a different premise. They see housing as more than physical shelter. They begin with the natural desire of individuals to use dwellings to expand their possibilities and participate in small societies. People buy into a community as much as they do a set of rooms. Why not start with their social needs first?

This type of architect is still rare. But an early pioneer, Balkrishna Doshi of India, was honored last week with the Pritzker Prize, which is the “Nobel” of architecture. Mr. Doshi is known for designing low-cost housing in India that, as he puts it, empowers the “have-nots” to live well in homes made with inexpensive building materials and designed to create deep connections in shared spaces.

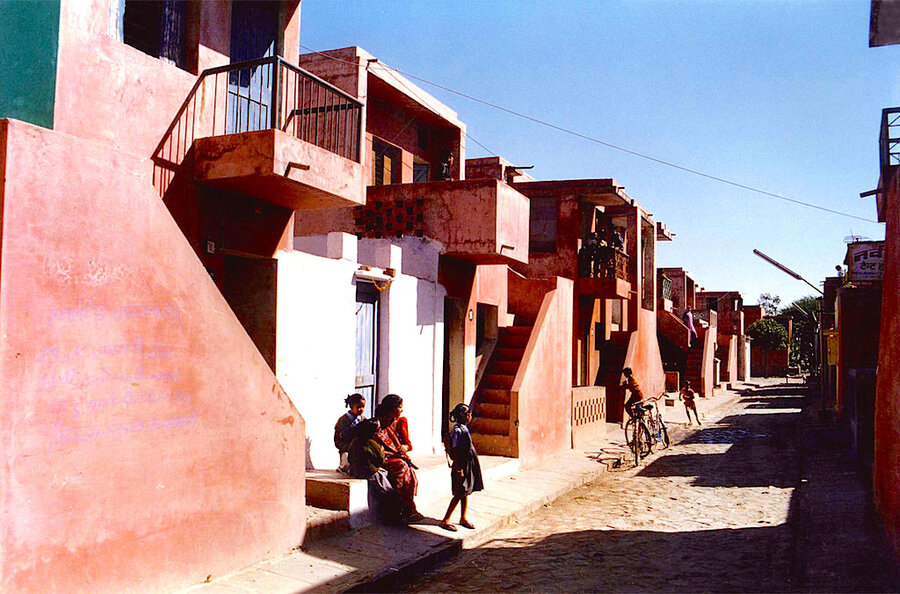

His most noted success is a low-cost housing scheme in the city of Indore for some 80,000 people. It uses prefab materials that allow for easy expansion of living quarters and includes a network of passages and courtyards to forge communal living. The prize committee noted his ability to understand “how cities work” as living organisms.

Or as Doshi once put it, “Planning is not merely physical growth, but also spiritual and cultural, all hinged on availability of resources.” A community of homes must rely on connected lifestyles and the “virtuous skills of the locals.” Homes must allow for self-discovery. And ideally, he says, all aspects of a person’s life, from housing to education to recreation, should be within a half-hour walk.

“The promise of a home is not a limited hope, but the sky becomes the limit,” he told the Guardian newspaper.

In a world marked by rapid communications and transport, Doshi’s work feeds the aspirations for traditional society within new structures. Many of his buildings, while built with modern concrete, also use local crafts, such as mosaics.

An architect, Doshi often says, must turn “refuges into homes, houses into communities, and cities into magnets of opportunities.” Perhaps that can become the motto for designers and developers of new rental communities in the US.