50 years on, why the moon landing still inspires

Loading...

The new movie “Yesterday” imagines what the world would have missed if the Beatles had never existed. A similar question might be asked about what life would be like today if, in July 1969 as the Fab Four were recording “Abbey Road,” three American astronauts had not landed on the moon.

From the moment they did land, history became divided into “before” and “after” the first visit to another celestial body by humans.

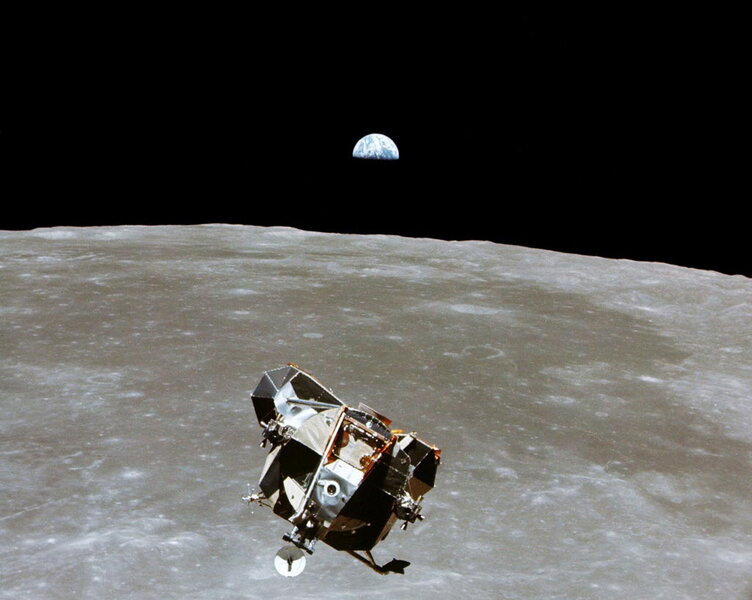

A half-century later, another compelling question is this: What if Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin had not safely made it to the lunar surface or had failed to return their Eagle spacecraft to the orbiting command module and Michael Collins? Earlier missions had vividly demonstrated the dangers of space exploration. As in any great discovery, expecting the unexpected is the norm. And fear is only one more obstacle to conquer.

In the turbulent times of the 1960s, one common question was this: “Why spend so much money on NASA at a time of war and social unrest?” Why look to the stars when so many suffer on Earth?

An answer to that question came in a call by President Richard Nixon to the astronauts as they left their bootprints on the Sea of Tranquillity. “Because of what you have done, the heavens have become a part of man’s world,” he said, and “it inspires us to redouble our efforts to bring peace and tranquillity to Earth.”

New tools for human tranquillity were indeed a NASA spinoff. Writer Norman Mailer wrote that the project set engineers and computer programmers to dream “of ways to attack the problems of society as well as they had attacked the problems of putting men on the moon.”

The landing was not just a boost to human confidence or new physical comforts. “I want my children ... to see a country that stands for something more than just consumption,” said former NASA administrator Daniel Goldin.

The globally televised event was a transcendent moment that reflected an unmet need to know and understand creation. “I do believe that there is a deficiency in the American spiritual diet which space exploration can help us remedy,” noted American historian Daniel Boorstin. That ongoing “diet” is represented in the name of a NASA rover on Mars since 2012: Curiosity.

Religious texts have long expressed the human wonder about creation and the eagerness to understand it. “When I consider thy heavens, the work of thy fingers, the moon and the stars, which thou hast ordained; What is man, that thou art mindful of him?” the Bible’s psalmist asked, and then concluded, “Thou madest him to have dominion over the works of thy hands; thou hast put all things under his feet” (Psalms 8:3-6).

A recent Gallup poll found 91% of Americans said they were proud of the country’s scientific achievements, a higher percentage than were proud of the military (89%) or economic achievements (75%). When thought soars, achievements follow. “The devotion of thought to an honest achievement makes the achievement possible,” the founder of The Christian Science Monitor, Mary Baker Eddy, wrote more than a century ago.

For Armstrong, the landing was only a beginning: “There are great ideas undiscovered, breakthroughs available to those who [search them out]. There are places to go beyond belief.”

The world of 2019 presents no lack of problems. Yet solutions now seem easier because that landing by the Apollo 11 astronauts keeps reminding us that when motives are lifted up, the limits in the human experience are left behind.