- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usMonitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Monitor Daily Intro for May 5, 2017

What is the internet?

That’s a pretty meta question for a Friday night, but it’s one that you might consider as you tap and click your way into another weekend of streaming, shopping, and … well, at this point, just about everything else.

In the coming weeks, the Trump administration is poised to try to roll back another of the Obama administration’s policies. The noise that you’ll hear as a May 18 FCC proposal on internet regulation nears will be starkly political – all about competition, censorship, jobs.

Expect the “net neutrality” debaters to use creative metaphors to cast the internet in a couple of different ways: the way a utility works (with the flow of content pulled by customers) or the way retail works (with the terms of its flow dictated more by the companies that push it). The metaphor that wins favor may help determine the outcome of the attempted rollback. A deeper issue: As the internet nears true utility status, should the real focus be on providing the best access to the most people?

Now to the five stories we’ve chosen for you today.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

American quest: income, but with stability, too

Economic data has clear value. It also has limits. Today’s flurry of indicators seemed to us an opportunity to look at why traditional barometers like jobless rates and wage growth may no longer paint an accurate picture of how Americans are feeling financially.

From afar, the lot of the typical American worker looks relatively good these days. At 4.4 percent, the unemployment rate in April reached a 10-year low, the Labor Department reported today. But just beneath the surface, that picture gets muddier – with even many in the middle class on shaky ground. The new “The Financial Diaries,” which tracked low-income and middle-class families for a year, found the typical family had more than five months in which their income swung by 25 percent or more. That volatility can lead to heightened insecurity and make it hard to save or plan for the future, the book’s authors say. Take Kieran Ridge, who owns a painting business in Boston. Ridge Painting & Restoration has thrived, but the work is highly seasonal, and dipping into the family’s savings during winter months to get by isn’t out of the ordinary. “I earn three times as much during the busy season as I do during the winter,” Mr. Ridge says. “Even then I have weeks where there are three checks coming in, and weeks where there are no checks at all.”

American quest: income, but with stability, too

Which would you rather have: a higher-paying job, or a more predictable one?

Taking a bird’s-eye view of upward mobility probably would lead to the first answer – more money is always a step up. But look beneath the surface, and the second is a deeper concern for a growing swath of Americans. Not knowing how much money is coming in every month, or even every week, can make it hard to cover everyday expenses and even harder to get a leg up on things like saving for retirement and paying for education.

For Kieran Ridge, who owns a business painting houses and commercial buildings in wealthy neighborhoods of Boston, income fluctuations are part of the job. Ridge Painting & Restoration has thrived since he started the business in 2009, so much so that Mr. Ridge’s wife recently left a six-figure job in management at Restoration Hardware to stay home with the couple’s two small children.

But his work is highly seasonal, and dipping into the family’s savings during slow winter months to get by isn’t out of the ordinary. “I earn three times as much during the busy season [from about April to November] as I do during the winter months,” he says. “Even then I have weeks where there are three checks coming in, and weeks where there are no checks at all. We just try to save when it’s busy and dip in when it’s slow.”

Those peaks and valleys, however, are no longer a problem solely for small-business owners, or even the very poor. Jonathan Morduch and Rachel Schneider discovered them, time and again, in the finances of families profiled for their book, “The Financial Diaries: How Americans Cope in a World of Financial Uncertainty,” released in April. Over the course of a year, Mr. Morduch, an economist at New York University, and Ms. Schneider, a financial services expert, headed up a team that tracked the cash flow of 235 low- and middle-income households.

And even many of those with steady jobs, living in good neighborhoods, were on shaky ground. The typical family tracked during the project had more than five months during the year in which their income swung 25 percent higher, or lower, than the sum total of their income averaged out over 12 months. One couple in the book, Becky and Jeremy, make a solid middle-class income on the aggregate from Jeremy’s work repairing trucks on commission, but dip below the poverty line six months out of the year.

“The volatility was experienced not just at the bottom,” says Morduch. “It’s a bigger problem for the poor, but one we see well into the middle class.”

The Financial Diaries project tells a broader story about the economy. It’s one of heightened insecurity, driven by a confluence of factors: a broad shift in the job market, higher living costs, and employees taking on more of the financial risks traditionally borne by their employers in the form of things like retirement savings contributions and a higher proportion of income coming from tips and commission. “This is something you can’t see from the usual snapshot,” Schenider adds.

Additionally, it bolsters the argument, made previously in investigative works like Barbara Ehrenreich’s “Nickel and Dimed,” as well as by the tailwinds that propelled Donald Trump to victory in the 2016 presidential election, that traditional metrics of success, satisfaction, and economic progress are increasingly disconnected from the day-to-day financial struggles and anxieties of most Americans.

Most top-down economic data is “looking over an interval of time that is long enough to mask the volatility,” says Diane Lim, an economist with the Conference Board.

What the big numbers aren’t telling us

From afar, the lot of the typical American worker looks relatively good these days. At 4.4 percent, the unemployment rate in April reached a 10-year low, the Labor Department reported Friday. The number of people filing for jobless benefits now stands at a 17-year low. Wages are rising slowly but surely.

But just beneath the surface, that picture gets muddier. A Gallup index of economic confidence among Americans is just barely positive, despite the low jobless rate. Unemployment and jobless claims numbers don’t capture the growing cohort of workers who are marginally attached to the workforce, or stringing together multiple streams of income. People who have done some freelance work in the past 12 months now make up approximately 35 percent of the US workforce, according to freelancing website Upwork and the Freelancers Union. A study by Harvard and Princeton economists found that the share of Americans in alternative work arrangements – from temp jobs to contract workers – rose from 10 percent in 2005 to nearly 16 percent in 2015.

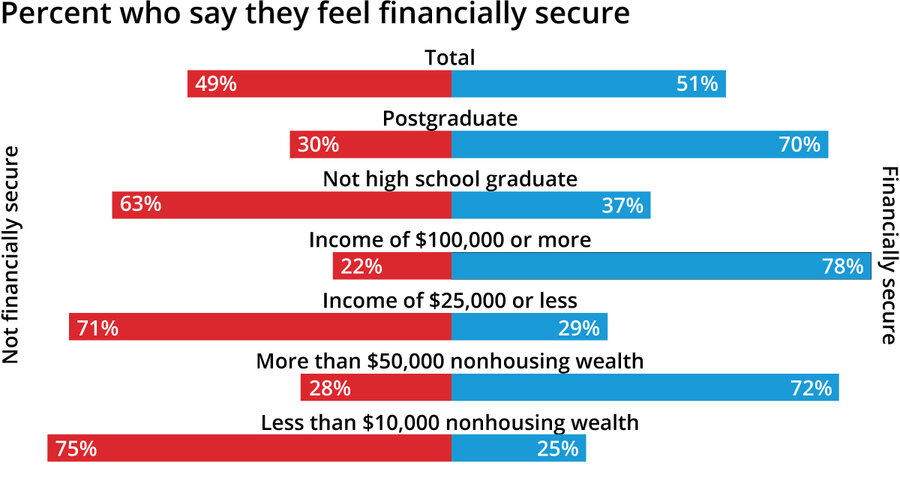

As a result, finding surer footing is a dominant, and growing, priority. In fact, when given the choice between moving up the income ladder or having more income stability in a 2015 Pew study, 92 percent of Americans picked stability – an increase of 7 percentage points since 2011.

"It’s not just about having a job [anymore], it’s about the quality of the job,” Morduch says.

The decline of manufacturing and other union-protected jobs has given way to a rise in service sector work that is “traditionally lower-wage, and where people are likely to be subject to schedule changes on a weekly or even daily basis,” Schneider says. At the same time, she adds, “the cost of living has been rising. There’s less ability to put aside a cushion and have slack in their week-to-week budget.”

How to cope?

This necessitates constant, active budgeting by the families profiled in the “Financial Diaries.” They clip coupons, pay off small loans to families by doing chores and other housework, and have to make day-to-day calls on when, exactly, they can pay their mortgages on a given month. A financial emergency, like a medical bill or car repair, can knock them off their feet even if they have solid annual earnings.

Haley Hamilton, a bartender and freelance journalist in the Boston area, has seen her income range from $1,200 in tips from a single table to less than $400 in a week. She compensated for the uncertainty intrinsic to her work in the first few years by just working all the time. “I’d go do a reporting gig all day and then tend bar at 5,” she remembers. “It wasn’t sustainable.”

Now, she works three shifts a week tending bar. Still, the possibility of a major setback is never far from her mind.

That kind of heightened financial volatility can make it nearly impossible to subscribe to the traditional financial advice for getting ahead: Set a budget, stick with it, and squirrel away the extra. People are trying to “get some discipline and structure into their lives, but also have some flexibility, and those things are fundamentally incompatible,” Morduch says.

Even Ridge, the painter, is aware that his booming business could take a turn due to factors beyond his control. “A sudden downturn [in the housing market] would really hurt me in the slow season,” he says. "But right now something always seems to fall into place.”

Some in the financial services industry are starting to tackle this growing reality. Even, a Silicon Valley start-up, offers a subscription service aimed at smoothing out the ups and downs of people with volatile paychecks into something resembling a regular salary. PayActiv, a payroll program for businesses, allows workers to access their earnings when they need them, not just during traditional pay periods. And some in the retirement industry are starting to build short-term savings considerations into their products, Morduch says.

But unless the problem of instability is addressed with more urgency, Morduch and Schneider argue, there could be consequences for the economy at large. “You don’t want to extrapolate too much from 235 households, but the inability to save long term and build up buffers make them even more vulnerable to downturns,” Morduch says. Any financial shock would be absorbed by individuals, and not by large companies and institutions more equipped to cushion the blow. That has the potential to worsen the nature of the downturns themselves, he adds. “The risk isn’t on the right shoulders.”

The Pew Charitable Trusts

Share this article

Link copied.

Why GOP hard-liners have suddenly become more pragmatic

The reality of governing has a way of enforcing shifts in approach. It can chasten. It can also mean taking on the mantle of leadership – including balancing principles with pragmatism.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

What happens when hard-liners suddenly find themselves responsible for governing? Surprising things, sometimes. Just six weeks ago, the group of far-right Republicans called the Freedom Caucus helped kill the first major piece of Trump-era legislation. This week, they played a crucial role in pushing the GOP health-care plan over the finish line. That indicates that the hard-liner group – born out of the tea party movement – looks to be climbing the learning curve of governing. During the Obama years, “it was a lot easier to be … the brick wall,” one former member told us. Now the caucus is realizing the buck stops with Republicans. They are the ones in charge. Or as Rep. Mark Meadows, the Freedom Caucus chairman, put it: “I think the epiphany is that this is a critical piece of legislation that we’ve been making campaign promises on for seven years, and if I can’t deliver here, I need to go home.”

Why GOP hard-liners have suddenly become more pragmatic

Their nickname around Congress is the “hell no” caucus – a group of Republican hard-liners in the House that is notorious for its blocking power.

But the conservative House Freedom Caucus played a crucial role in pushing the GOP health-care plan into the end zone in the lower chamber on Thursday. The group negotiated. It compromised. And then it helped carry the ball down the field on legislation that would dismantle key parts of the Affordable Care Act. Six weeks ago, these hard-liners stopped the bill cold.

They’ll probably never be called the “heck yeah” gang, but the Freedom Caucus – born out of the tea party movement – looks to be climbing the learning curve of governing. Like House Republicans generally, they’re adjusting from an opposition mind-set to one of a party that holds the levers of power in Washington and has to act on its promises.

That is contributing to a greater sense of teamwork among fractious House Republicans as they set their sights on the next big promise: tax reform.

“We learned to play as a team and work together. It’s a big moment,” said Rep. Tom Cole (R) of Oklahoma, who is close to the GOP leadership and has seen the Republicans’ internecine battles up close.

Observers caution it’s too early to tell whether the Freedom Caucus, which has roughly 30 members, will be more in step with the rest of the GOP conference on issues beyond health care. Reportedly the group is already working on tax-reform proposals so it can have input on the front end of the process instead of scrambling to react.

“We really only have one data point that suggests they are more focused on governing than they used to be,” says Matthew Green, a professor of politics at Catholic University in Washington and an expert on the House speakership.

And part of governing is learning to work with the other side. Caucus members – along with a lot of other House Republicans – voted against this week’s bipartisan budget to fund the rest of this year. Caucus member Rep. Dave Brat (R) of Virginia, says that if governing means continuing to run a $600 billion deficit, he’s not voting for that. He's also wary of potential Senate changes to the health-care bill.

Even so, says Professor Green, it was unusual to see the caucus involved in developing a compromise on the GOP’s American Health Care Act and then almost unanimously supporting it.

Road to a compromise

The compromise was initially drafted over the two-week April recess by Rep. Tom MacArthur (R) of New Jersey, who is a co-chair of the more moderate Tuesday Group of House Republicans. While at the beach with his family, he sketched out his ideas and shared them with Speaker Paul Ryan (R) of Wisconsin and Freedom Caucus chairman Mark Meadows (R) of North Carolina.

The speaker pushed the talks down to the two members, encouraging them to work it out, according to Congressman Cole, who is not in the Freedom Caucus. A committee chairman who helped write the underlying bill, Rep. Greg Walden (R) of Oregon, became the “indispensable broker” providing staff and expertise, Cole said.

The leadership “needed to push the discussion down into the bowels of the conference, because at some level, this was not just about policy,” Cole told reporters after the Thursday vote.

“There’s a lot of deep bitterness and very personal feelings … that needed to be worked through on a person-to-person or group-to-group basis, and really, leadership is not the place to do that,” he said.

What emerged from the MacArthur-Meadows negotiations was a compromise that allows states to opt out of two Obamacare requirements: federal minimum-coverage standards, known as “essential health benefits,” and guaranteed coverage of “pre-existing conditions." States, though, would have to take other measures such as setting up “high-risk” pools to handle these patients.

“We’re a states’ rights kind of group, so we all believe from our standpoint the more decisions that can be made at the state level the better,” Congressman Meadows told reporters April 27. The opt-out waivers will pave the way to lower premiums, said Meadows, and lower premiums were the key to his caucus’s support for the bill.

A contrast with recent past

Over the past couple of months, the North Carolinian has been a peripatetic sprinter in search of a deal – at the president’s resort in Mar-a-Lago, at the White House, in the House, and over at the Senate, where he says he has consulted with 14 or 15 senators.

But it was not long ago that Meadows was spearheading hard-liners’ efforts to partially shut down the federal government (2013), oust House Speaker John Boehner (2015), and derail the Republicans’ first viable attempt at Obamacare repeal in March. The caucus opposed it on the grounds that it was not a real repeal, and because of the rushed, closed manner in which the bill was drafted. At least one member quit the caucus over its earlier refusal to back the GOP's health-care bill.

Meadows’s actions might lead one to think of him as a hard-knuckled sort with a scowl, but he actually has a convivial personality, say those who know him. He wants to be liked – and understood – as evidenced by his willingness to talk with reporters long after the House chamber has emptied out after a vote.

“He is one of the nicest guys you’d ever want to meet,” says former Rep. Matt Salmon (R) of Arizona, who retired from the House at the end of last year and was a founder of the Freedom Caucus. “He just really has a good bedside manner.”

It might not seem like it, but Meadows believes in collaboration and wants to get to “yes,” Mr. Salmon says of the North Carolinian, who is in his third term and has a business background in real estate.

That doesn’t mean, though, that Meadows and other members won’t play hard ball. As in Donald Trump’s “Art of the Deal,” they’ll ask for much more than they know they’ll get, says Salmon.

On taxes, he says, they’re more likely to side with President Trump than Speaker Ryan. Most caucus members are supply-siders, who believe low taxes will be paid for by economic growth. Ryan favors a border tax to offset some of the cost of a tax cut, but Salmon says the caucus won’t fall for that “gimmick,” which will be passed on to consumers.

An epiphany for Meadows

Like many Republicans, Salmon says the change in the caucus – he calls it Freedom Caucus 2.0 – has much to do with the changed political fortunes of the party, which now controls both ends of Pennsylvania Avenue.

During the Obama years, “it was a lot easier to be the stop-gap, the brick wall,” he says. Now the caucus is realizing the buck stops with Republicans. They are the ones in charge.

Indeed, when asked on Thursday what had brought him around on health care, Meadows told a crowd of reporters:

“I think the epiphany is that this is a critical piece of legislation that we’ve been making campaign promises on for seven years, and if I can’t deliver here, I need to go home.”

In South Korea, coping with a perpetual threat

What does it do to a society to stand at the brink of war for six decades? Staff writer Michael Holtz went to Seoul to explore that question, and to help gain understanding of South Koreans’ approach to preparedness as tensions rise to its north.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

-

By Michael Holtz Staff writer

Seoul, South Korea, a metropolis of 25 million people, has nearly 200 miles of subway tracks and more than two dozen universities. It also has 4,000 underground shelters – a visible reminder that the capital is just 35 miles from the border with North Korea. Technically, the two are still at war, and every now and then Pyongyang threatens to turn the South into a “sea of fire.” Tensions around North Korea’s missiles and nuclear ambitions have intensified lately, but many in Seoul are accustomed to living with uncertainty. South Koreans have internalized what Park Myoung-kye, a professor at Seoul National University, calls a “cold war mentality.” Can that attitude last as provocations rise? Nam Gyu-han is a retiree who lost his father and brother during the Korean War. “Because I’m old, there’s nothing for me to lose,” he says. “But I’m worried about the next generation. They’re the ones who will have to face this.”

In South Korea, coping with a perpetual threat

The shaded lawns and winding paths in Yeouido Park offer a respite from this frenetically modern city. But the park’s elongated shape betrays one of its original functions, which was decidedly less peaceful: an airstrip for emergency evacuations in the event of a North Korean attack.

The strip of land the park sits on, now covered in cherry trees and picnic tables, was once one of the world’s largest public squares. Commissioned by President Park Chung-hee in 1970, the square was made of concrete – not grass, as its designers had initially proposed – to make it more suitable for aircraft. If North Korea were to attack, the thinking went, planes could easily land on the square and whisk away government officials who worked nearby. The National Assembly building is 2,000 feet away.

Then, in the 1990s, Seoul’s municipal government transformed the square into the city’s version of Central Park – its history largely forgotten as more and more Seoulites became nonchalant toward North Korea’s belligerent posturing and seemingly empty threats.

“I’m not worried,” says Seo Young-chae, who was having a picnic with his wife and two daughters at Yeouido Park on Friday. “The situation may seem more dangerous to people outside South Korea, but people here are going about their usual lives.”

During decades of tension between the two Koreas, which technically remain in a state of war even after the 1953 armistice, South Koreans' anxiety toward their northern neighbor has ebbed and flowed. But despite the occasional uptick, many people have settled for something in-between preparing for the worst (a nuclear attack) and expecting the best (a peaceful reunification or coexistence). They've learned to live with a degree of uncertainty that seldom disrupts their daily lives.

That attitude has been put to the test in recent weeks, amid a string of ballistic missiles tests and live-fire military exercises in the North. Meanwhile, the Trump administration has deemed "strategic patience" a failure, and warned of possible military action, while pressuring China to rein in its neighbor. The administration has also deployed a nuclear-powered submarine and aircraft carrier to Korean waters in an effort to thwart the North’s nuclear ambitions.

Yet many South Koreans have responded to the escalations with a collective shrug. Park Myoung-kyu, a sociology professor at Seoul National University, says the relative calm reveals how distant the fear of a second Korean War has become.

“South Koreans have lived under this situation for more than 60 years,” Dr. Park says. “In Korean society, a kind of cold war mentality has been internalized. That’s why people seem so normal or indifferent to the current situation.”

That indifference is palpable in Seoul; the city’s vibrancy appears undiminished. If it weren’t for the bomb shelter signs that hang at every subway entrance, it would be easy to forget how the city has prepared for a North Korean attack. About 4,000 underground shelters are located around the city in subway stops, tunnels, and public buildings. The metropolitan government maintains an online map where people can find the closest one.

Shin Gi-wook, a sociology professor and director of the Korea Program at Stanford University, says he’s worried about how lax South Koreans have become about the possibility of an attack. He still remembers the air-raid drills that occurred on the 15th of nearly every month when he was growing up in South Korea. The drills became less frequent in the late 1990s and have virtually disappeared since then. The last large-scale drill occurred in December 2010, three weeks after a North Korean artillery strike killed two soldiers and two civilians on South Korea’s Yeonpyeong Island.

“I’m someone who believes that you have to get ready for the worst case scenario,” Dr. Shin says. “If something does happen the consequences would be huge.”

About 25 million people, or half of the South Korean population, live in the Seoul metropolitan area. The center of the city is 35 miles from the border, where hundreds of North Korean artillery pieces are stationed within firing range. A 2012 study estimates that up to 64,000 people could be killed in the first day of an artillery barrage – most in the first three hours.

James Kim, a research fellow at the Asan Institute for Policy Studies in Seoul, says a person’s perception of the North Korean threat is often a reflection of his or her age. Polls conducted by the Asan Institute show that South Koreans who lived through the Korean War are often more fearful of renewed conflict. So too are people under the age of 20.

“There is a heightened level of anxiety that is due to their unfamiliarly with these kinds of provocations,” Dr. Kim says. “Young Koreans simply haven’t seen this enough yet.”

Kim says a new complication is President Trump, whose controversial statements have put South Koreans of all ages on edge. In the past two weeks, the US president warned of a “major, major conflict” with North Korea and declared he would make South Korea pay $1 billion for an advanced missile-defense system, THAAD, whose controversial installation began last month. The White House has backed off the demand, but not before it rattled nerves across South Korea. How to handle Mr. Trump has become a major policy question ahead of the country's presidential election on Tuesday.

“There’s more anxiety about what the Americans are doing than what the North Koreans are doing,” Kim says. “Is Donald Trump serious about the possibility of war or is it simply a lot of saber rattling?"

Nam Gyu-han, a retiree who walks through Yeouido Park almost every day, is old enough to have experienced the Korean War firsthand. Sitting on a bench, the septuagenarian grows solemn as he tells the story of how his father and older brother were killed during the conflict. But Mr. Nam says he’s no longer fearful of North Korea on a personal level. He’s become used to the hostile, uneasy peace of the last six decades. He’s just not sure how long it can last.

“Because I’m old there’s nothing for me to lose,” Nam says. “But I’m worried about the next generation. They’re the ones who will have to face this.”

Can ‘compassionate conservatism’ make a comeback?

Politics centered on lifting people up, not tearing them down, has been cast as an antidote to today's coarsened political culture. Linda Feldmann gets us reacquainted with one proponent who was also a recent guest at a Monitor Breakfast in Washington.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

In a week that saw Republicans push through a controversial health-care bill, Ohio’s GOP Gov. John Kasich has a different vision, which he calls the “politics of the heart.” But is there a market for his views, as laid out in a new book, “Two Paths: America Divided or United"? In the 2016 campaign, Mr. Kasich and Donald Trump offered different approaches to the sense of powerlessness by “the little guy” in a changing nation. While the GOP has largely embraced Mr. Trump, Kasich wants to change the party again, and move the nation beyond the hyper-partisanship that has gripped its politics. If his popularity in Ohio is any indication, there may be a strong appetite for Kasich’s approach. “I do think Kasich is right that we’re experiencing a crisis of belonging,” says Robert P. Jones, author of “The End of White Christian America.” “It’s just that the two parties have so far put together two mutually exclusive visions of what that looks like.”

Can ‘compassionate conservatism’ make a comeback?

It was a signature moment in John Kasich’s 2016 campaign.

At an event in South Carolina, a young man stood up and spoke of a series of personal tragedies, his voice wavering. He was in “a really dark place,” he said, but had found hope in the Lord, his friends, and “my presidential candidate,” Governor Kasich of Ohio.

Kasich walked over and gave the man a hug.

A year later, Donald Trump is president, and Kasich is still a governor. But the Republican hasn’t given up promoting his vision for the country, which he calls “the politics of the heart.” It is the focus of his new book, “Two Paths: America Divided or United.”

One path, Kasich says, turns fear into hatred, and divides people. The other, “higher” path turns fear into hope as people take strength from one another.

“If you’re living in the shadows, if you’re weak, if you’re powerless, we run over you, because you don’t have any political clout. And that’s just wrong,” Kasich said at a recent breakfast hosted by The Christian Science Monitor. “I think that in our country, everybody has to have a sense that they have a shot, they have a chance, and that they have an opportunity.”

Kasich & Trump's contrasting approaches

Kasich’s decision to expand Medicaid for low-income Ohioans under the Affordable Care Act exemplifies this approach. On Thursday, he took to Twitter and slammed the health-care bill passed by House Republicans as “woefully short” on the resources needed to help the most vulnerable citizens.

In a way, President Trump and Kasich offered different approaches to the same phenomenon – a sense of powerlessness by “the little guy” in a changing nation and world.

Trump won by twinning his outsize, outsider persona with the rhetoric of populism and nationalism. Kasich, a two-term governor and former nine-term congressman, deployed the quieter rhetoric of a more mainstream, moderate conservatism, and fell short.

But Kasich is still part of the national conversation, and is showing certain tell-tale signs: the book, the media tour, the online fundraising. Once out of office, at the end of next year, he intends to maintain his political organization and speak out on issues.

At the Monitor breakfast, Kasich insists another presidential campaign is unlikely. “I mean, my wife would kill me if she ever –” Kasich interrupts himself and waves to an invisible Karen Kasich. “I’m not, sweetie!” he calls out. “That’s not why I’m here!”

More fundamentally, though, lies a deeper question: Is there a market for Kasich’s “politics of the heart”? Trump’s job approval ratings are at historic lows for this stage of a presidency, but most Republicans are still with him – including the white working-class voters who handed him bellwether Ohio.

In fact, Kasich’s power may be in his ability to garner attention as the successful governor of the seventh-largest state. At a time when faith in government is low, Kasich stands out with a 59 percent job approval rating in Ohio.

“If Kasich’s success in Ohio is any indication, there may be a good-sized appetite” for his brand more broadly, says John Green, director of the Bliss Institute of Applied Politics and a dean at the University of Akron.

Bill Vasu, a technology CEO in Chagrin Falls, Ohio, is a Democrat, but says that it would have been a tough call for him to decide how to vote if it had been Kasich vs. Hillary Clinton.

“I could sense how much the campaign had taken the edge off his right-wing tendencies, and made him a lot more understanding of the people and their needs,” says Mr. Vasu.

Just to be clear: Kasich is still a Republican – “I haven’t given up on my party,” he insists – but his party has changed. It has embraced Trump, more or less. Kasich wants to change the party again, and move the nation beyond the hyper-partisanship that has gripped its politics.

'A crisis of belonging'

We’ve seen this movie before, or at least a version of it. In 1988, George H. W. Bush called for a “kinder, gentler nation” on his way to the presidency. In 2000, his son George W. Bush campaigned successfully as a “compassionate conservative.”

Mr. Green sees Kasich’s “politics of the heart” as a bit different. The Bush family’s sense of compassion came from a place of “noblesse oblige,” in which “the well-to-do have certain responsibilities, because of their privileged position,” he says.

“Kasich is still a working-class kid from McKees Rock, Pa., and to him it’s all about opportunity and compassion,” Green adds. “It’s not that the more fortunate have a special obligation. It’s that everyone has an obligation to enhance opportunity, but also to take care of the needy.”

At the Monitor breakfast, with reporters from two dozen national news outlets at the table, Kasich is asked what he means by “the politics of the heart."

“I think it’s about really loving our kids and getting out of our comfort zone to educate them,” he said. “I think it’s writing a health-care bill that keeps in mind the people who are drug-addicted and mentally ill.” Or when a problem arises with community and police, a diverse group addresses the issues and considers everyone’s concerns – including those of the police.

“I do think Kasich is right that we’re experiencing a crisis of belonging,” says Robert P. Jones, CEO of the Public Religion Research Institute in Washington and author of “The End of White Christian America.” “It’s just that the two parties have so far put together two mutually exclusive visions of what that looks like.”

Kasich doesn't fit comfortably in either camp. But to be clear, he's no big-spending liberal. He believes lower taxes and less regulation can help grow the economy, and produce the resources needed to help the less fortunate. After he leaves the governor’s office, he will push for a balanced budget amendment to the US Constitution.

An imperfect messenger

Kasich is complicated – a man of deep faith who can be prickly. And he may be an imperfect messenger for his politics of the heart.

“I’m a flawed guy, sometimes I don’t spend enough time with people, sometimes I’m short,” he says. “But I don’t want to be that way … and when people point it out, I’ll turn around and try to do something to fix it.”

Of course, it’s too soon to be talking 2020 in a serious way, though Trump himself has already registered for reelection. Taking on the sitting president of one’s own party can be a fool’s errand. The bottom would have to fall out of Trump’s support among Republicans for any serious Republican candidate to consider getting in.

Kasich says he wants Trump to succeed. “It’s sort of like being on an airplane; you want to root for the pilot,” the governor told reporters after an Oval Office meeting in February.

Then there’s the question of whether loyal Republicans would even consider Kasich, who wrote in John McCain for president.

John Altes, a student at the University of Michigan, likes Kasich’s experience and approves of Medicaid expansion. He supported Kasich in the primaries last year, but now feels “he’s sort of motivated by vanity.” He points to Kasich’s recent visit to New Hampshire, home of the first primary.

Other Republicans point negatively to Kasich’s decision to boycott the Republican National Convention last summer in Cleveland. Instead, he held a separate, campaign-like event at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

But Kasich tells the Monitor he has no regrets about not welcoming the delegates to his home state.

“I wasn’t going to go to a party where I wasn’t going to behave or say something good,” he says. “I didn’t agree with the tone or what I heard, so why would I go? I know people were going to be mad at me, and they’re still mad at me. But that’s life.”

In waters off border zone, a swim for humanity

The politicized debate over border security often ignores a sobering tally: The US Border Patrol reportedly documented more than 6,000 migrant deaths in Arizona, California, New Mexico, and Texas between October 2000 and September 2016. Whitney Eulich reports on an event that wrapped up just hours ago, when a group of international athletes turned the focus on – and delivered tangible help to – the families of migrants who perished.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

A cold, six-mile swim isn’t for the faint of heart. For the group of elite open-water swimmers who dived into the Pacific this morning, though, the swim from Imperial Beach, Calif., to Tijuana, Mexico, was nothing short of a mission. As they crossed the maritime border, swimming past the point where the border fence slips into the sea, they did so in recognition of those who haven’t survived their overland attempts. Today’s Pan-American swim – with participants from Mexico, South Africa, the United States, Israel, and New Zealand – raised funds for the Colibrí Center for Human Rights, a Tucson-based organization that supports the families those migrants leave behind. It isn’t a race, these athletes say. Nor is it a political statement. “This swim goes far beyond” that, says Mariel Hawley, a top open-water swimmer from Mexico. “It’s about helping grieving families, about people who risk their lives for opportunity somewhere else.”

In waters off border zone, a swim for humanity

Leticia Orozco and Manuel Aguirre are leaning against a fence, listening as their granddaughter recounts her latest swimming accomplishment. She’s ten years old on this sunny Saturday afternoon, and despite her proud smile that beckons a congratulatory hug, she and her grandparents don’t move any closer. The giant, rust-colored slates of the US-Mexico border wall stand between them.

The physical structure separating the United States and Mexico takes on many forms along the nearly 2,000-mile border, but this is one of the most dramatic points. The fence runs through a small square in Tijuana known as Friendship Park, where loved ones on either side of the border often gather on the weekends to catch up, cry, and sometimes protest. But several yards from the park’s concrete plaza, the fence undulates down a sandy hill, jetting out into the Pacific Ocean – where it abruptly ends.

The imagery is striking: A man-made structure dictating strict territorial lines fades away into open waters that run freely from one town, country, and continent to the next.

As children splash in the surf, it’s easy to question if anyone’s tried to swim across this border.

Park officials say it’s not common. But today, 12 people from five countries are doing just that. The participants are adamant this isn’t a political protest – they are trying to raise money for families whose loved ones died trying to cross the border.

The swimmers say any symbolism one might read into a group of international athletes swimming past a border wall amid a moment of tough-on-immigration talk in the US is not the message they’re trying to send.

“The wall already exists, we know it exists,” says Mariel Hawley, the first Mexican woman to finish the so-called Triple Crown of open water swimming, referring to the segments of a border wall that already spans the US-Mexico frontier.

“Maybe it will get taller, but this swim goes far beyond [a wall],” she says. “It’s about helping grieving families, about people who risk their lives for opportunity somewhere else.”

The group of open-water swimmers, including Mexicans, Israelis, South Africans, Americans, and a Kiwi, take off from San Diego’s Imperial Beach Friday morning and will swim to Tijuana, Mexico, raising funds for the Colibrí Center for Human Rights, based in Tuscon, Ariz. The organization focuses on supporting families whose loved ones disappeared or perished along the US-Mexico border.

The swim is above board, its organizers say, with the US Coast Guard and the Mexican Navy informed about the event. The swimmers won’t have to tread water to go through customs: A group of kayakers will accompany them, carrying their passports and visas and handing them off to other kayakers waiting in Mexican waters.

Politics aside, “when you are in the ocean, you are always thinking about liberty,” says Antonio Argüelles, the founder of Mexico’s Triathlon Federation and the first person to complete the Triple Crown of open water swimming twice.

The high tensions surrounding today's conversations around immigration in the US – where President Trump's campaign and first 100 days in office often focused in on border security – may overshadow the long history of migration between Mexico and the United States.

For decades, families have migrated north for seasonal work and then returned home to Mexico. But in the 1990s, crossing the frontier became more difficult with the implementation of stronger border controls, essentially closing that circular loop of migration. As a result, more migrants began trying deadly desert crossings. Since the turn of the century, crossing clandestinely has become increasingly dangerous, with the rise of drug cartels that rely on income from human trafficking, kidnapping, and extortion. It’s become nearly impossible to cross the border without hiring a “guide,” who, despite charging a hefty sum of money, doesn’t always deliver on getting migrants safely across the border.

It’s now common for people to embark on the journey north, only to disappear. Between 1990 and 2000, the average annual migrant death toll in southern Arizona was 12. Between 2002 and 2014, that average jumped to 173 deaths per year.

“When I talk about the swim in Mexico, people aren’t asking me how much money I’ve raised or what the swim will be like,” says Ms. Hawley, who was drawn to supporting the Colibrí Center’s work helping grieving families and aiding them in their search for closure. She lost her own husband recently, after an illness.

She says Mexicans “are asking me for more information about the [Colibrí] center. Because so many families here have someone who has left and who they haven’t heard from, and they never knew this kind of center or support existed.”

The swim is 10 kilometers in cold water of about 60 to 63 degrees Fahrenheit. For athletes who have world-famous swims like crossing the English or Catalina Channels under their belts, however, the difficulty factor is relatively low.

“My longest swim was 23 hours and 18 minutes. So to swim 2.5-3 hours; it all depends on what you consider hard,” says Mr. Argüelles, who went to the US to finish high school and attend Stanford University with the support of a Speedo executive. Argüelles was inspired to swim competitively after Mexico hosted the 1968 Olympics, and met Bill Lee, then president of Speedo, when he was selling swim caps at a local meet years later.

“We might see a shark, but you can’t [get angry] about that since we are swimming for migration, after all,” he says with a chuckle.

The event is not a race, and the swimmers will glide through the water as a pack, in solidarity, Hawley says.

“Any of us could be migrants,” says Argüelles. “I saw this as an opportunity to lend a hand and embrace a theme that is increasingly global…. We want to contribute to a better future.”

The swimmers are expecting to be greeted by roughly 200 high school students on the beach in Tijuana. Hawley hopes the teenagers will be inspired to overcome their own challenges.

In Mexico, she says, many grow up hearing positive stories about migration. Not just that aunt who crossed the border and sends back money to help build new homes or put relatives through school, but Hollywood-style happy endings. Stories like the brain surgeon at John’s Hopkins who entered the US without proper documentation, or the astronaut who grew up as a migrant farmer in the US.

“But not all migration stories are like this,” she says. “All four of us Mexican swimmers live and work in Mexico. And these are kids who might migrate one day. We are trying to tell them that there are great opportunities here. But you have to keep working and studying. I want to be a motivation for them.”

Argüelles sees it another way. He’s one swim away from becoming the first Mexican (and the seventh person in the world) to complete the “Ocean’s Seven” swim series, which includes tackling The English Channel and the Tsugaru Strait in Japan.

“This group includes some great swimmers of the world,” he says of today’s team. “To do this, you need to put in a lot of effort and you need to persevere.”

“That’s something all of us have in common with migrants. We all have dreams we want to achieve and we have to work hard to achieve them.”

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

When conscience, not guns, decides a democracy

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By The Monitor's Editorial Board

As Venezuela’s protests grow, its security forces may be pressed to use more violence, and soldiers or police may determine the country’s democratic future. It’s worth noting that in almost any protest in history that led to a democratic revolution – Ukraine in 2014, Tunisia in 2011, the Philippines in 1986 – many of the unsung heroes were soldiers or police officers. When ordered to fire on peaceful demonstrators, they refused. And a dictator was then forced to flee. With pro-democracy protests against President Nicolás Maduro becoming larger and more frequent, and more cracks opening among his supporters, a moment of conscience by security forces may be coming to Venezuela.

When conscience, not guns, decides a democracy

Pick almost any protest in history that led to a democratic revolution – Ukraine in 2014, for example, or Tunisia in 2011 or the Philippines in 1986 – and you’ll find many of the unsung heroes were soldiers or police officers. When ordered to fire on peaceful demonstrators, they refused. And a dictator was then forced to flee.

Such a moment of conscience by security forces may be coming to Venezuela. As pro-democracy protests against President Nicolás Maduro become larger and more frequent, more cracks have opened among his supporters. Polls show less than a quarter of Venezuelans support him. And as Maduro’s legitimacy fades and the economy enters its fourth year of recession, he has relied even more on forceful repression – and the shaky allegiance of armed forces. In the past month, dozens of people have died during peaceful protests.

The latest top official to openly criticize the Maduro government is Attorney General Luisa Ortega Díaz. In March she denounced yet another unconstitutional grab for more power and Maduro’s use of armed thugs against dissidents. Her criticism led the opposition speaker of the sidelined legislature, Julio Borges, to make this request of the military: “Now is the time to obey the orders of your conscience.”

Any soldier or police officer that refuses to shoot nonviolent protesters is on solid moral and legal ground. Under a 1990 United Nations agreement called Basic Principles on the Use of Force and Firearms by Law Enforcement Officials, security personnel have a right to ignore commands to shoot if there is a possibility of killing innocents.

In Venezuela, soldiers may have also heard of a saying by Latin America’s famed 19th-century liberator, Simón Bolívar: “Cursed is the soldier who turns the nation’s arms against its people.” And they may feel emboldened by recent demands from a majority of Venezuela’s neighbors in the Organization of American States for free and fair elections and the release of political prisoners.

New democracies have often been created or reborn after a mental revolution by soldiers who, rather than shoot, embraced their fellow citizens and their cause of liberty.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

On responding with love, not hate

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By Mark Swinney

To hate or to love? It may sound extreme, but that’s a choice all of us face in some measure every day. When we hear about corruption, crime, and wrongdoing, our first thoughts might be of anger, even hatred. But we all have the ability to respond in a way that can actually heal instead of add to the problem. God is Love, and enables us to love. Christ Jesus' devotion to love, despite the great wrong done to him, gave to humanity the perfect example of Love. He knew we were capable of loving even our enemies, because we are all truly Love’s own children. The question we ask ourselves should not be, “Who now deserves hatred?” Rather, we can ask, “How can I respond with love?”

On responding with love, not hate

With my work taking me to several different countries these past few years, I’ve picked up on what seems like an increase in how quickly people respond with hate when they hear the news of the day. But I’ve also seen an increase in how quickly people are willing to love.

The news we watch and read often uncovers wrongdoing, and we may feel pressed into accepting that we are supposed to detest someone or something. While people, organizations, and companies should certainly be held responsible for immoral mistakes they make, how we respond to news of injustice, corruption, etc., will determine whether we’re contributing to healing or just making the problem worse.

Hatred has never had a healing effect on anyone or anything. Responding to hatred with love has the ability to heal and uplift, as can be seen in the life of Christ Jesus. He proved that spiritual grace and love can relieve the frustration that tempts us when we are exposed to unjust, selfish, and toxic behaviors. Love that conquers evil is a love that reflects God, divine Love.

This divine Love holds everyone within its embrace, without exception. That’s because even people we may only see as cruel, the eternal Love knows only as its own spiritual offspring, completely good. Jesus faced the harsh judgment of the religious leadership of his day, the icy, self-serving indifference of the political leadership, and the violent cruelty of the army. But he was victorious by drawing deeply and wholeheartedly on infinite Love.

He encouraged us not just to love those who love us, but to take care to love even those who act hatefully toward us and persecute us (see Matthew 5:44). He knew humanity was capable of this unselfed love, because he knew we are all truly Love’s own spiritual children. And Jesus proved for all that the world’s most powerful weapon is the love of God.

Most of us have learned from our own experiences that hatred harms the hater so much more than the hated. And many of us have also experienced, in some degree, that selfless prayer and action based on God’s love overcomes sin, fear, injustice, and evil. Such a powerful weapon for achieving good mustn’t remain hidden; it must be brought out into the open and employed constantly.

“Divine Love corrects and governs man. Men may pardon, but this divine Principle alone reforms the sinner,” writes Monitor founder, Mary Baker Eddy, in her book “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures” (p. 6). So why would we ever resort to hate?

We don’t ever need to! It’s good to be one of the people on our globe who is quick to love. The question of the week shouldn’t be, “Who deserves hatred?” Drawing upon the same omnipotent and ever-present Love that Jesus drew upon, we can each ask ourselves a more healing and cleansing daily question: “How can I love?”

A message of love

Iberian splendor

A look ahead

Thank you for reading today – and for following along during this product’s run-up. We’re moving out of beta mode now and into regular production! On Monday, Monitor staff writer Harry Bruinius examines a moment in which the United States seems to be grappling with its identity – with Americans wrestling with personal conscience and the meaning of religious liberty.