- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Monitor Daily Intro for June 15, 2017

Fred Warmbier was a model of parental fortitude when he spoke today of his reunion Tuesday in Ohio with his son Otto, who was cruelly imprisoned for 17 months in North Korea. Mr. Warmbier’s profound love for Otto, who has suffered serious injury, framed his harsh criticism of the North. He also had pointed words about the previous administration’s efforts to achieve his son's release, and expressed gratitude to the current one for gaining it.

Dealing with government in such a situation can feel at times like staring into a black hole, as I found when our son went missing while studying in Tehran, Iran, in late 2015. But where else would one turn?

At a time of great disdain for government, it reminds me how much we need it to be a place where thoughtful and caring people aspire to work – not to avoid at all cost. Soon after we concluded our son had been detained, we called the State Department. There were no guarantees we wouldn’t be frustrated or angered as we pressed for his freedom (which came 40 days later), or that our son wouldn’t be caught up in a calculus different from our own. But when we made that call, it was 3:30 a.m. – and an attentive official answered. She knew where to start and how to try to move forward. And the work began.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

That other agenda item: stop election hackers next time

Former Monitor writer Dan Murphy put it succinctly on Twitter yesterday: 1. Special Counsel Robert Mueller's Russia/Trump/Flynn/etc investigation. 2. Growing vulnerability of our elections. 1 & 2 are different. 2 is more important.

-

Jack Detsch Staff writer

Can the United States stop Russia from meddling in future elections? That’s a key question that has been largely overshadowed by daily news about whether the Trump team colluded with Russia or had any improper dealings with Russian nationals. But behind the scenes, Congress is working to prevent déjà vu in 2018 and beyond. It’s focusing on three main areas: figuring out exactly what Russia did in the last election and determining appropriate countermeasures; levying sanctions on Russia; and clarifying the rules of the game when it comes to digital meddling and waging cyberattacks. There are four separate congressional investigations into Russian interference, which have served to heighten American awareness of hacking attempts – and that in itself can have a deterrent effect. But even as Congress and defense officials consider this challenge, James Lewis, a senior fellow at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, warns that Moscow may already be moving on to Plan B. “They may think up a new set of tactics, realizing, it worked once and everybody knows about it,” says Dr. Lewis. “They need a new bag of tricks.”

That other agenda item: stop election hackers next time

In the past week, a series of dramatic congressional hearings have sought to plumb possible collusion between the Trump campaign and Russia – or possible presidential obstruction of justice over the matter, which special counsel Robert Mueller is now reportedly investigating.

But this spotlight, while an important line of questioning into last year’s interference, overshadows other steps that Congress is taking to prevent Russian meddling in future elections. Absent an administration that is staffed up or a president inclined to go hard on Moscow, Congress is looking to define its own strategy.

“We don’t really have a Russia strategy” to prevent a repeat of election meddling, says James Lewis, a senior fellow at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington. “Congress is trying to figure out what that should be.”

Specifically, it’s looking at several areas: sanctions, what exactly Russia did in the last election and appropriate countermeasures, and US digital defenses.

New sanctions on Russia

On Thursday, the Senate took concrete action against Russian interference in the 2016 election, passing a set of Russian sanctions as part of an Iran-sanctions bill.

Among other things, Thursday’s bill codifies present sanctions against Russia relating to its actions in Ukraine and enacts new ones over Moscow’s activities in Syria and its interference in the US presidential election. It also gives Congress the ability to stop any effort by President Trump – or any president – to roll back sanctions on Russia. Trump has publicly doubted the intelligence community’s finding that Russia interfered in the election, and lawmakers are worried he will move to roll back sanctions.

“We cannot let Russia’s meddling in our elections go unpunished, lest they ever consider such interference again,” said Senate minority leader Charles Schumer (D) of New York on the Senate floor Wednesday. The bill passed by a veto-proof majority of 98-2. The House has yet to take it up, but sentiment there for Russia sanctions is strong.

Secretary of State Rex Tillerson was on Capitol Hill this week warning against anything that would restrict the president’s “flexibility.” He told the Senate Foreign Relations Committee that the administration needs to be able to turn up the heat, but also “maintain constructive dialogue.”

Mr. Lewis says that while the actual economic effect of sanctions is limited, Russians hate them – and they’re particularly painful for Russian President Vladimir Putin, says Lewis, because Mr. Putin had expected Trump to lift sanctions.

What exactly did Russia do?

Four congressional committees are looking into various aspects of Russian interference, but the Senate and House intelligence committees have made it their mission to find out what exactly Russia did.

Yes, they are looking at the collusion and obstruction questions, but they are also fact-finding on the election meddling, and are expected to produce reports that summarize their findings and make policy recommendations.

“Time’s a wastin,’ ” said Rep. Steny Hoyer (D) of Maryland, speaking to reporters this week. The next election is less than 18 months away.

On the Senate side, members of the committee express confidence that they can finish their work in time to make a difference in those midterm elections. But some members of the committee say their work is already having a positive effect.

“Just the public hearings and the public conversation already gets the attention of the states,” says Sen. James Lankford (R) of Oklahoma. One of the problems last year was that “no one exposed it early.”

The senator, walking briskly to this week’s hearing with Attorney General Sessions, says his committee’s policy recommendations are going to be “exceptionally important.” Will it be able to resolve tensions over the role of the federal government in state-administered elections?

“What happens when the FBI comes to an entity and says, ‘You have a problem,’ and they say ‘I don’t,’ ” he asks. “Because that’s happened in the past.”

Defending against hacking

Members of Congress are working to clarify the rules of the game when it comes to digital meddling and waging cyber attacks.

Sen. Mike Rounds (R) of South Dakota is heading up a new Senate Armed Services committee panel that will examine how the Defense Department responds to digital tumult – and what level of attack constitutes cyber warfare. The US is still establishing a system to coordinate how and when government agencies respond to digital attacks that don’t cause physical damage or death.

After last year’s election campaign, then-Homeland Security Secretary Jeh Johnson labeled election infrastructure as critical infrastructure. That would allow US government funding to go to protecting vote tabulation systems, voter registration databases, and voting machines from digital attack – though this raises federal-state questions.

Indeed, Sen. Chris Coons (D) of Delaware, says there is “not the bipartisan will there yet” to strengthen the infrastructure of voting at the state and local level and invest in a new generation of voting machines.

Meanwhile, top defense officials say the US military is boosting its preparedness for dealing with cyber attacks – efforts made possible by congressional funding.

On Tuesday, Joint Chiefs of Staff Chairman Gen. Joseph Dunford told senators this week that 70 percent of the Defense Department’s 133 cyber mission teams – tasked with penetrating and disrupting foreign networks – were ready to be deployed in cyberspace.

Defense Secretary James Mattis also testified that the agency is on track to elevate the status of Cyber Command – the US military’s top offensive hacking unit – to a unified combatant command, giving elite cyberwarriors a direct line to the Pentagon’s brass.

There’s growing evidence that suspected Russian digital interference, which includes hacks, leaks, and fake news that US intelligence agencies say aimed to harm Hillary Clinton’s candidacy, was even more extensive than previously understood.

On Tuesday, Bloomberg reported that Russian hackers managed to infiltrate voter databases and software systems in 39 states. And National Security Agency documents leaked to The Intercept last week indicated that a Moscow-based intelligence agency may have attacked a company that provides voting-management software in several US states.

The scope of the threat is leading Pentagon officials to analyze defensive vulnerabilities in their systems. In Senate testimony, Mr. Mattis confirmed that the agency is working on a broad strategy to counter digital threats from Russia, and is honing intelligence and cyberdefensive capabilities ahead of its release.

But even as Congress and defense officials consider this challenge, Lewis warns that Moscow may already be moving on to Plan B.

“They may think up a new set of tactics, realizing, it worked once and everybody knows about it. They need a new bag of tricks.”

Share this article

Link copied.

Russia tries ‘cyber-democracy’ to link a society with its leaders

By talking – at length – to Russians today, President Putin tried to show his population he was listening to their questions. But he also seemed to be fortifying the idea that he has all the answers.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

The Kremlin effort to build a network of alternative channels for top authorities to interface directly with the public is as old as the Vladimir Putin era. Best known of these is President Putin's annual “Direct Line” telethon, the latest of which occurred Thursday, when he answers questions from linked studio audiences around the country. But as a new presidential election looms in 2018, the Kremlin is intensifying its embrace of digital innovations to try to improve the waning faith of Russia’s electorate in the existing political system. In theory, the new “e-democracy” tools will allow citizens to directly petition the Kremlin, which will in turn analyze and redistribute the appeals downward with orders for lower levels of government. But past efforts have not been successful because those lower levels were unwilling or unable to respond – a problem that the new effort may not change. “The initiatives are one thing,” says Vlada Muravyova, an adviser to the Civic Initiatives Committee nongovernmental organization. “What officials do with them are quite another.”

Russia tries ‘cyber-democracy’ to link a society with its leaders

Since becoming Russia's top leader almost two decades ago, Vladimir Putin has developed various methods of talking to the Russian public over the heads of other institutions and authorities, with the aim of establishing a problem-solving dialogue directly with the people.

Best known of these is his annual “Direct Line” telethon, the latest iteration of which happens Thursday. In the event, Mr. Putin answers questions from linked studio audiences around the country, as well as emailed and SMS queries. He often directly addresses acute social problems such as inter-ethnic relations, solves people's personal problems on-the-spot, and even discloses intimate details of his personal life.

But the TV spectacle is only the tip of the iceberg – one that the Kremlin is hoping to grow into a wired-up, ultra-modern open society in which citizens will be able to deliver their grievances, petitions, and legislative initiatives in person to their leaders without having to depend on the mediation of 20th century institutions like legislatures, opinion polls, or the media.

Now, as a new presidential election looms, the Kremlin is looking hard at indications such as extremely low voter turnout in last September's parliamentary elections that suggest Russia's electorate is losing faith in the existing system. In response, it is intensifying its embrace of digital innovations that claim to fix the problems.

Even some critics say the idea has promise. “Everything is changing in the world, not just Russia,” says Vlada Muravyova, an adviser to the Civic Initiatives Committee headed by liberal ex-Finance Minister Alexei Kudrin. “There's new technology, the younger generation is becoming active and people are dissatisfied with classical channels of communication. Decision-making should be quicker, and public participation stepped up....”

But, the critics add, the Kremlin's plan has come amid concerted measures to limit genuine electoral competition, to prune the media landscape, and to sideline independent public opinion polling. “It's good to have mechanisms for bringing new initiatives to the attention of government,” Ms. Muravyova says. “Though, the initiatives are one thing, and what officials do with them are quite another.”

'A real chance to move forward'?

The effort to build a network of alternative channels for top authorities to interface directly with the public is as old as the Putin era.

As he prepared to return to the Kremlin for his third term in 2012, Putin issued a series of public "manifestos" to set forth the policies he intended to follow. One of the least-noticed of these was a lengthy blueprint for building a "participatory democracy" using the latest information technology, published in the Moscow daily Kommersant.

"It is necessary to adjust the mechanisms of the political system so that it captures and reflects the interests of social groups in a timely way, and ensures that those interests are addressed," Putin wrote. "That would not only increase the legitimacy of the authorities, but also people's confidence that they act fairly.... We must be able to respond to the demands of society, which are growing increasingly complicated and, in the information age, are acquiring fundamentally new features."

While the annual TV spectacle is arguably the most overt such effort, the many thousands of queries, criticisms, and grievances that pour in to the show – most of which, despite the typically four-hour program length, do not get aired – are carefully collected, collated, and analyzed by the Kremlin to determine broad currents of public opinion and identify sore points that might require further action.

Last month Putin moved to apply that approach beyond the telethon, by mandating the presidential service to collect and analyze all citizens' appeals and petitions, and then redistribute them downward with orders for lower levels of government to deal with them.

The main agency responsible for organizing and maintaining this ambitious digital project to reinvent government is the Information Democracy Foundation, a nonprofit organization that says it is funded by various Russian IT firms, and headed by Ilya Massukh, a former deputy minister of communications.

Reached by telephone, Mr. Massukh said that e-democracy is not intended to substitute for established institutions but to supplement them and provide new tools for overcoming the notorious inertia of Russian bureaucracy.

"Democracy is not in the genes of Russians, so these new ways of communicating directly between government and society offers a real chance to move forward," he says. "It's a logical step, and President Putin is quite serious about using new technology to improve management. He is a big supporter of e-government."

But Russia's formal political system established by the constitution, with its autonomous institutions such as parliament, is being eroded purposefully as the Kremlin seeks greater and more direct power, says Nikolai Petrov, a professor of political science at Moscow's Higher School of Economics.

"But, obviously, something new must be invented to create the impression of close contact with Russian citizens, who are becoming more sophisticated in many ways," he says. "So the Kremlin is developing various methods of getting feedback from society, bypassing not only elections, but also regional authorities, whose [communiques to the Kremlin] are no longer seen as reliable."

A technology-politics disconnect

In 2013, the Kremlin ordered Massukh's Foundation to set up an internet portal, called the Russian Public Initiative, which boasts that it has since posted over 10,000 petitions on its website. Each appeal purportedly originates from a grassroots source, and can be voted upon directly by website visitors. When a petition addressed to Moscow authorities reaches 100,000 votes, for example, it will be forwarded to an "expert panel" to determine what action should be taken. It's no guarantee that the appeal will be granted.

One example is a grassroots petition asking authorities to cancel the "Yarovaya Law," a sweeping set of anti-extremism measures that accord vast powers to security services and severely limit civil rights, including those for religious minorities. The petition was adopted and forwarded for consideration to the authorities with a request to cancel the law. Not mentioned on the site is the fact that the "expert panel" rejected the petition, finding the law fully in conformity with the Russian constitution, though it ruled that some amendments might be considered in future.

"The Russian Public Initiative was supposed to become a platform of true 'people's power,' a means of self-organization for citizens that offers the government and parliament ways to correct errors," says Anita Soboleva, a member of the Kremlin's Human Rights Commission. "After a while it became obvious that it doesn't work as such a channel, because even those initiatives that got enough votes were never turned over to the competent authorities to be considered."

She argues the key problem with all this electronic paper shuffling is that everything comes back to the same old officials, who now may have more work to do, but are as free as ever to ignore, punt, or misrepresent the public's complaints.

"All proposals are sinking in a viscous ooze," she says. "Officials may just write that they have, indeed, studied, analyzed and summarized [the public inputs], but find it impossible or impractical to make any changes, or require more time to sum up, clarify, specify, etc. There is not really any more genuine communication than there used to be."

Why Turkey squeezes those who would aid Syrians, Kurds

President Erdoğan's deepening suspicion of Western influence wouldn't seem to immediately threaten the 2.5 million refugees living in Turkey. But it is complicating their already difficult lives by reining in a key source of help: international aid groups.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 8 Min. )

For years international relief organizations have pumped hundreds of millions of dollars in humanitarian aid from Turkey into Syria, delivering critical food and supplies through risky cross-border operations. But with Syria now in its sixth year of civil war, the organizations’ relations with Turkey have soured, badly. One reason: the anti-Western sentiment that swelled after last summer’s coup attempt against Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan. In Mr. Erdoğan’s successful campaign for broad new powers in April, anti-foreign rhetoric played a prominent role. Pro-government media have denigrated foreign relief workers as spies. Turkey has targeted aid groups and their foreign and Syrian staff with closures and arrests. Two US-based organizations, Mercy Corps and the International Medical Corps, were recently expelled. One Syrian who works closely with the international relief community on Turkey’s southern border says the Turkish crackdown makes little sense now. “Syria needs those NGO workers,” says the Syrian. “We need everyone, because there are millions of people who are in need.”

Why Turkey squeezes those who would aid Syrians, Kurds

After two months of detention in Turkey, the four Syrian staffers from a Danish relief agency were released and expelled from the country, part of an escalating battle between the Turkish government and Western aid organizations that is complicating relief efforts for Syrian victims of war.

The four were flown to Sudan, where Syrian nationals do not need visas. That was a bit of good news for DanChurchAid officials, who were relieved they were not forced to return to Syria, now in its sixth year of a brutal civil war.

But the staffers’ extradition in late May came in the midst of an unprecedented period of uncertainty for international non-governmental organizations (INGOs), which have pumped hundreds of millions of dollars in humanitarian aid from Turkey to Syria, delivering critical food and supplies through risky cross-border operations.

The Turkish hostility toward the international aid agencies is one byproduct of anti-Western sentiment that skyrocketed in the wake of last summer’s coup attempt and was perpetuated for months until the national referendum in April, which gave President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan sweeping new powers.

The challenge for aid agencies has been exacerbated by Turkish sensitivities over INGOs working in ethnic Kurdish areas, and the boldness of Turkish security forces under an on-going state of emergency, amid a campaign by pro-government media that has denigrated foreign relief workers as spies who should be expelled.

In recent months, as Turkey has targeted INGOs and their foreign and Syrian staff with closures and arrests, two US-based organizations are among a handful that have been expelled. Mercy Corps was shut down in March, and the International Medical Corps (IMC) was closed in April, with four foreign staffers expelled and 11 Syrians detained.

The collision between Turkey and INGOs features a perfect storm of clashing motivations: in their desire to help, the big-budgeted INGOs have often bent the rules, arousing suspicions of corruption and running afoul of Turkey’s oft-changing legal requirements and its growing suspicion of foreigners on the border.

“Why now? That’s a question mark, and just the Turks have the answer,” says a Syrian who works closely with the INGO community in Gaziantep, a hub for Syrian relief aid agencies on Turkey’s southern border, who asked not to be further identified.

The Turkish crackdown makes little sense now, he says, with needs inside Syria as great as ever and several populations on the move, including from around the Islamic State-controlled city of Raqqa, where a US-led coalition offensive has begun to oust the so-called Islamic State from its self-declared capital.

“Syria needs those NGO workers. How can the help go inside Syria without their work?” asks the Syrian. “The Turks can’t handle everything. It’s a lot bigger than their NGOs. Everyone is working Syria, even OCHA [the UN’s Office for Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs] is not enough – we need everyone, because there are millions of people who are in need.”

A tense history

Turkey has never been happy with the presence of the foreign relief community and their Syrian staff, whose work blossomed along its southern border as Syria’s 2011 uprising turned into the region’s most significant proxy war. The conflict pits President Bashar al-Assad and his allies Iran, Russia, and Hezbollah, against a broad array of anti-regime rebel forces – some of them jihadists linked to Al Qaeda, as well as ISIS itself – supported variously by the US, Saudi Arabia, Qatar, and Turkey.

While Turkey grappled with an influx of 2.9 million Syrian refugees, and for years turned a blind eye to Islamist militants crossing into Syria to fight, it also became the most sizeable base for aid agencies helping Syrians inside rebel-held areas across the border.

But Turkey’s calculations have been changing, aid workers say, with a surge of militant attacks last year by ISIS and Kurdish militants, the attempted coup in July, and the defeat of rebel forces in the northwest Syrian city of Aleppo in December. Then came the April vote on presidential powers.

“From now on, we will not allow any Europeans who are spying in our country under various titles, whether it be individuals or organizations,” Mr. Erdoğan said in late March, during a heated referendum campaign in which he vilified Germany and the Netherlands as “Nazis.”

Since the crackdown began, with police visiting offices to check registration documents and work permits, foreign and Syrian staff at some INGOs have been working from home or coffee shops, to lower their profile and avoid possible arrest.

Turkey plans to cancel all existing INGO registrations and, under new rules, require re-registration within three months, according to an internal document from the UN’s OCHA leaked to Voice of America in early March.

“There’s definitely an impact, where Syrians are getting less support than what they really, really need,” says a senior Western relief worker in Gaziantep.

Before it was closed down, for example, Mercy Corps was assisting up to half a million Syrians inside the country, and another 100,000 refugees in Turkey. IMC claimed to support 100 hospitals and health facilities with medical supplies and salaries. Cutting off support has made other INGOs scramble to fill the gap.

“It is a constant moving target of, ‘How do we see who really needs help?’” says the Western aid worker. Other INGOs “were picking up all these facilities that have suddenly lost all financial support.”

Mercy Corps a surprise target

OCHA suggests the aim of the Turkish government is “to choose which organizations they want to keep in the country,” and notes that Turkey’s interior minister convened a meeting of all regional governors to discuss new rules, VOA reported.

One of the largest non-profit INGOs in the world, Mercy Corps spent $34 million last year on Syria-related relief, much of it funded by the US and European governments. Mercy Corps was told abruptly that its registration had been withdrawn, leading to an immediate firing of 300 relief workers.

Mercy Corps was a surprise initial target, senior aid workers say, because they were registered and had close ties to government in Ankara. Still, not all their staff work permits were approved for the districts in which they work – a rule rarely enforced previously – and they were heavily involved in Kurdish areas of Syria, despite Turkish disapproval.

“We have been playing this constant game, especially after NGOs got registered, of the ever-evolving interpretation and enforcement of the various laws,” says the senior Western aid worker.

“So we’ve all got dirty laundry, to be brought up if they want to shut you down,” says the aid worker. “The fact is, it doesn’t matter how compliant we were, whether or not the law was clear or not, every single NGO working here has broken laws at some point. Some inadvertently. Some because there was no law in place to tell us how to do it, [like] the transfer of money.”

After-effects of the coup

The restrictions on INGOs come as Turkey still reels from the aftermath of the coup attempt last July, which has seen a purge 140,000 Turks from government jobs, the arrest of nearly 50,000, and a state of emergency which enables closing any NGO without reason.

The public vilification of INGOs intensified after the coup attempt. For example, the pro-government Sabah newspaper last August ran a story with the headline, “Foreign NGOs are fanning the flames of chaos.” It claimed that aid agencies crossed into Syria with “bags” of money to fund and divide Syrian opposition groups.

This March, Sabah claimed INGOs were funneling cash to the outlawed Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) in Syria from Hatay province, with the assistance of cadres of Fethullah Gülen – the US-based cleric whom Turkey accuses of ordering last year’s coup attempt.

“The aid agencies in Hatay are full of spies,” ran Sabah’s headline. The story claimed that INGOs were not trying to help people, but lay the groundwork for civil war in Turkey.

“It’s not that they hate foreigners, but they worry about foreigners. They think that everyone is not doing good for Turkey,” says the Syrian who works with the aid community. The rules for work permits for Syrian staff have become clearer, he says, but weeks ago one local Syrian NGO delivering food applied for 30 work permits, and got only two.

“Of course, no NGO can run with two people,” he says. NGOs “aren’t doing something bad; they are still helping people. Why are [Turks] making their work as difficult as it as difficult as it is now? There is no excuse for that.”

Corruption investigations

Shutting down the INGOs and raising pressure on others has shaken the relief community, which senior Western relief workers say grew too fast the first years of the conflict, with uncommonly large US and EU-funded budgets applied in chaotic situations.

Turkish officials and media have been given grist for complaint by the US Agency for International Development’s Office of the Inspector General (OIG). Since 2015 it has been investigating alleged fraud schemes that involve “bid rigging, collusion, bribery, and kickbacks,” which have led to the suspension of $239 million in program funds among four NGOs in southeast Turkey, according to OIG data released March 31.

Three of those were identified as big players global organizations – IMC, the International Rescue Committee, and the Irish group Goal – in a May 2016 investigation by IRIN, a media venture once run by the UN that focuses on the relief world.

IRIN noted that all three INGOs grew quickly as the Syria crisis took off. IMC funding more than doubled, for example, to $232 million, from 2011/2012 to 2014/2015. Goal’s funding for Syria leapt 94 percent from 2013 to 2014.

Those increases mirror similar expansion by the UN, which saw the value of goods and services procured in Turkey alone jump from $90 million in 2012 to $339 million in 2014, reports IRIN.

The impact is sizeable: Though the Inspector General’s office says that just one IMC staff member lost their job, IRIN reports that 800 people “involved in IMC contracts in Turkey” were let go because of the USAID aid suspension.

“NGOs tend to think that we have this irrefutable positive impact,” says the senior Western aid worker in Gaziantep.

Turks are “looking at what they see as a security threat in all these foreigners around, who maybe were or maybe were not spies, maybe were having an impact, maybe weren’t following the rules, maybe were helping the enemy,” says the aid worker.

“Is it worth it to take all that risk to have 30 NGOs registered, of all shapes and sizes? Or is it better for them to narrow the field to ... 10 or 12 NGOs that have not really over-stepped in the ways that matter?” asks the aid worker.

“I just think the Turks have said, ‘Enough.’ ”

States work to close a nagging coverage gap for dental care

The most important thing about someone's smile is its warmth. But it can also reflect growing inequality among some populations in the US.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

For many Americans, dentistry is an important part of health care that’s priced out of reach, and Medicaid for the poor doesn’t close the gap. Only 15 states offer comprehensive coverage, and even then it’s complicated. Many dentists don’t want to accept the low reimbursement rates, and GOP legislation in Congress might roll back Medicaid further. Some states are trying a new tack. In Minnesota, Maine, and Vermont, dental hygienists are being trained to give basic dental care such as filling cavities at a lower price than standard dentists’ billings. It’s not a fix-all, but supporters say this idea of therapist licensing is – by reducing fees – helping dental practices expand to treat uninsured patients who might otherwise depend on charities. It also becomes more viable to accept Medicaid recipients with lower reimbursements than the privately insured. Harriette Chandler, a state senator in Massachusetts who’s sponsoring similar legislation, puts the opportunity this way: “We have hygienists who are active, well trained, and well equipped to help.”

States work to close a nagging coverage gap for dental care

It’s only 10 miles as the crow flies to Boston from this coastal city. For Dorothy Macaione, a 97-year-old with false teeth that no longer fit, it felt like a bridge too far.

But like many without insurance who can’t afford private dentists, she faced few good options. Which is how she found herself taking a public shared-ride service in May, headed back to a dental school in Boston for the next stage of discounted dental work.

Her first trip to Boston for a consultation had been long and exhausting, and this day would turn out to be even more so.

In the national debate over health-care, dental insurance is often overlooked. But its inequities run deep: One-third of Americans have no dental coverage. For the poor, Medicaid mandates dental coverage only for children, and it can be hard to find a dentist willing to accept lower rates. Families on a budget often forgo check-ups and wait for free clinics; some end up seeking urgent care in hospital emergency rooms. Teeth are often a class marker, a way to pick out society’s winners from its losers.

Enter the dental therapists.

In Minnesota and other states, dental hygienists are being trained to pull teeth, fill cavities, and do other basic dental care, all at a lower price than standard dentists’ billings. They are licensed as dental therapists, a mid-level position similar to that of nurse practitioner. A key benefit, say proponents, is that dental therapists can fan out into communities, visiting schools, health clinics, and nursing homes, targeting people who find it hard to get to a dentist’s office. Telehealth systems allow them to share records and consult with dentists on complex cases.

“We have hygienists who are active, well-trained, and well equipped to help these people. They can serve as caregivers for people who have no caregivers for oral health,” says Harriette Chandler, a state senator in Massachusetts who has sponsored legislation to license therapists.

A model from Minnesota

Maine and Vermont have passed similar laws. Several other states are also mulling legislation, says Kristen Mizzi Angelone, a dental policy expert at Pew Charitable Trusts, which has supported the legalization of therapists. Many are encouraged by what’s already happened in Minnesota, where therapists are helping to expand coverage, particularly in rural areas and poor inner-city communities, at a time when finding new money for public health spending is scarce.

“No matter what Congress does [on health-care] it’s clear that every state around the country is in a budget constraint, and there are millions of people who aren’t getting dental care,” says Ms. Mizzi Angelone.

In 2011, Minnesota created two categories of therapists. Advanced therapists, who have a wider scope of practice, make $40 to $45 per hour, compared with $50 to $78 for dentists, according to a Pew study. By lowering their costs, say advocates for therapist licensing, dental practices can expand to treat uninsured patients who might otherwise depend on charities. It also becomes more viable to accept Medicaid recipients with lower reimbursements than the privately insured, and to offer care on a sliding scale to those without coverage.

Last year, Senator Chandler sponsored a budget rider to authorize dental therapists in Massachusetts that passed the Senate unanimously but was dropped from the final budget amid strong opposition by dentists. The American Dental Association has argued that creating a new class of provider is risky, since procedures can be irreversible, and instead urged states to increase Medicaid spending.

Earlier this year, Chandler filed another therapist bill in the Senate; the same bill was filed by a House representative. Both are waiting for joint committee hearings.

A rival bill backed by the Massachusetts Dental Society would allow therapists to perform basic dental work, subject to strict rules on supervision and where they can work. Katherine Pelullo, a dental hygienist who represents the profession in the legislature, says that bill is overly restrictive and would limit the expansion of therapists, unlike Chandler’s bill.

Chandler says she would be happy to see either bill pass if it succeeds in expanding access in Massachusetts at a time when Washington appears poised to cut federal healthcare spending. “We have some people who are getting care for their oral health needs and other who aren’t, and may be scarred by that for the rest of the lives,” she says.

President Obama's Affordable Care Act (ACA) mandated dental benefits for children on Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program. In theory, that means all children in low-income families receive regular screenings, though experts point out that working parents often struggle to find appointments, given dentists’ hours and their reluctance to take Medicaid patients.

For adults, states determine their own level of Medicaid coverage; Massachusetts is among 15 states that provide comprehensive care, though it was cut during the "great recession." Overall, 5.4 million adults have received dental benefits under the ACA’s Medicaid expansion, according to the American Dental Association. The House bill that passed in May would roll back that Medicaid expansion, reduce future Medicaid funding, and would also allow states to apply for waivers from federally mandated areas of coverage, such as dental.

'To talk without messing up'

Macaione, who goes by Dot, isn’t eligible for Medicaid or MassHealth, as the program is known here. As a senior, she is enrolled in Medicare, but it excludes dental care. She doesn’t remember how many years she’s had her current set of teeth, nor when she last saw a dentist before her recent trips to Boston.

What she does know is how she's impeded by pain. “I want to be able to talk without messing up. I want to continue with my way of life,” she says.

That way of life includes volunteering in community organizations and running a small library in the senior housing where she lives in Lynn. It was from her neighbor, Irving Rouse, that she learned about Tufts University School of Dental Medicine in Boston, where trainee dentists see uninsured patients.

Mr. Rouse, who used to work at General Electric’s jet-engine plant here, also needed major work done on his teeth. He shopped around in Lynn and was told that he’d need to pay several thousand dollars, even after a discount for seniors. He calls it discouraging. “Once you get up to a certain age, they don’t want to bother with you,” he says.

So one morning in April, Rouse and Macaione boarded the van that would take them downtown to Tufts. It took three hours there in the traffic with multiple pick-ups, and Macaione fretted about what the dentists would say. “It was a little nerve-wracking,” she says.

That day, their consultations went well. “They were lovely people. They made us feel very comfortable. It didn’t feel like we were getting something for nothing,” she says.

Trips for treatment

Both were asked to come back to Boston to begin their dental work and given cost estimates. So they decided to team up again for the next stage of treatment.

Therapists aren’t a substitute for complex dental work like denture replacements, says Carolyn Villers, executive director of Massachusetts Senior Action Council. “It’s clearly not an immediate fix in providing comprehensive care to seniors,” she says.

But Ms. Villers says dental therapists could offer on-site checkups to retirees like Macaione, as well as make sure that seniors with their original teeth keep them intact. A 2009 survey of seniors in nursing homes in Massachusetts found that 59 percent had untreated decay.

Last month, Rouse and Macaione made their second trip to Tufts. But after Rouse was taken ill there, Macaione missed her ride-share home and had to call her daughter to come pick her up.

Macaione says she’ll go back to Tufts to resume her treatment, even if it means another long day. Still, she wishes there was affordable dentistry closer to home for people like her. “Why do we have to go to Boston?” she asks.

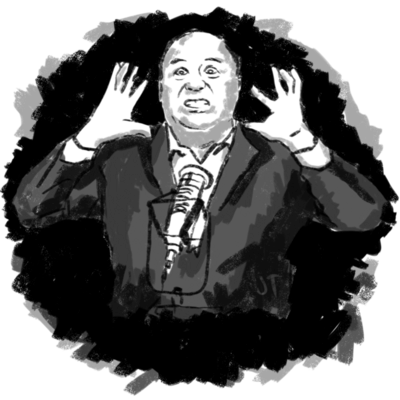

Megyn meets Alex: Heat rises around a high-profile interview

It's a fresh challenge for journalists: If they interview members of fringe news outlets that have acquired mainstream press credentials (and thus greater influence), are they exposing them or giving them legitimacy?

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Are there people who just shouldn’t be on the news? That’s the question that’s arisen ahead of Megyn Kelly’s June 18 interview with “Info Wars” provocateur Alex Jones, who has said that the Sandy Hook shooting was “a hoax” and that 9/11 was an inside job by the United States government. Behind the current furor is an ethical debate that is in many ways particular to the Trump era, observers say. The president, after all, has appeared on Mr. Jones’s show and granted him White House press credentials. Far-right and far-left conspiracy theories have haunted the fringes of the radio waves since the 1950s and ’60s. But with the far-reaching effects of digital technology and the rise of social media, such views have already been finding a wider audience – and, indeed, represent a substantial core of voters who, as Jones himself says, consider President Trump one of their own. But experts say that giving such fringe ideas a platform involves deeper risks to the country. “In my mind, I see it as less a story about the media per se, but a story about where we have come in the Trump era,” says political scientist Jeanne Zaino.

Megyn meets Alex: Heat rises around a high-profile interview

When NBC News host Megyn Kelly announced this week that her show would feature the radio host and conspiracy-promoting provocateur Alex Jones this Sunday, she may not have realized the furious backlash it would create.

Mr. Jones has on numerous occasions called the massacre of children at Sandy Hook “a giant hoax” that “clearly used actors” and that “pretty much didn’t happen.” (He since has backed off, calling himself a “devil’s advocate.”) His website has also advanced the conspiracy that the 9/11 terror attacks were actually an “inside job” by the United States government – a view shared by others on the fringes of both the right and left.

Some parents of the 20 children killed at Sandy Hook were outraged. Media critics, too, argued that Jones’s extreme views did not deserve such a prominent platform – and that the interview itself might have been designed to be provocative and controversial, meant to create buzz for Ms. Kelly’s new show on NBC.

On Tuesday, the group Sandy Hook Promise, founded by parents organizing to prevent gun-related deaths, disinvited Kelly from their annual gala. JPMorgan Chase pulled its ads; the social media hashtags #ShameOnNBC and #ShameOnMegynKelly began to trend.

In years past, the national media would indeed ignore such seemingly outlandish conspiracy theories, easily debunked and hardly worth the time to discuss, experts say.

Yet behind the current furor is an ethical debate that is in many ways particular to the Trump era, observers say. The president of the United States, after all, has appeared on Jones’s show and granted him White House press credentials. Before he was elected, President Trump, too, was a leading figure in the “birther” conspiracy, which questioned whether former President Barack Obama was a citizen. While in office, Mr. Trump has continued to make unsubstantiated claims, often through Twitter.

“In my mind, I see it as less a story about the media per se, but a story about where we have come in the Trump era,” says Jeanne Zaino, a professor of political science at Iona College in New Rochelle, N.Y. “And now there is a lot of pressure on the media to do things that, quite frankly, I don’t think they should be in a position of having to do. If this guy’s in the White House, if he’s got credentials and the ear of the president, then we should probably hear what the heck he’s saying.”

And with the far-reaching effects of digital technology and the rise of social media, such views have already been finding a wider audience – and, indeed, represent a substantial core of voters who, as Jones himself often says, consider Trump one of their own.

Kelly defends her decision

Kelly defended her interview with Jones this week, arguing that it is only her role to report ideas and people who have been elevated to influential roles.

“I find Alex Jones’s suggestion that Sandy Hook was ‘a hoax’ as personally revolting as every other rational person does,” Kelly said in a statement this week. “It left me, and many other Americans, asking the very question that prompted this interview: How does Jones, who traffics in these outrageous conspiracy theories, have the respect of the president of the United States and a growing audience of millions?”

“Our goal in sitting down with him was to shine a light – as journalists are supposed to do – on this influential figure,” she continued, “and yes – to discuss the considerable falsehoods he has promoted with near impunity.”

For critics, however, the issue is far more complicated. They argue that, despite the fact that Jones has already been legitimized by the president, the role of the press should be, in part, to preserve the quality of public discourse.

“That doesn’t mean that the news media has to basically throw out their standards, and say, OK, we’re going to start to give as much credence to such obviously ridiculous conspiracy theories as we do to people who are trying to tell us the truth,” says Anthony Fargo, director of the Center for International Media Law and Policy Studies at Indiana University. “It’s a grievous insult to the families of the victims of Sandy Hook to continue to publicize this lie,” he says. “There is no moral duty to put someone who has no credibility on the air to spread false information – which essentially is what is going on.”

And throughout US history, there have long been robust political fringes on both the left and right, notes Don Haider-Markel, chair of the department of political science at the University of Kansas in Lawrence. In the 1950s and '60s, for example, right-wing radio shows promoted the conspiracy that the US government was full of secret anti-Christian communists – a culture that in many ways helped to shape Jones’s current views.

Giving such fringe ideas a platform involves deeper risks to the country, Professor Haider-Markel says, and though he respects Kelly as a journalist and her reasoning behind interviewing him, he worries that featuring Jones and his views can legitimize a rhetoric that can become dangerous.

“People talk about conspiracy theories and inflammatory rhetoric on the right,” Haider-Markel continues. “But on the left, too, we went through a period like this in the '60s and '70s, where the left was so frustrated with the powers that be, the only actions they saw were to act out on the street. And that basically helped lead to instances of violence.”

Preserving 'American-ness'

Just one day after Haider-Markel made this observation, James Hodgkinson, an unemployed home inspector from southern Illinois who volunteered for the campaign of Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders, and who had reportedly made angry comments about Trump on social media, attacked Republican congressmen as they practiced for a charity baseball game in Virginia.

The shooting left House majority whip Steve Scalise and four others wounded. Investigators are seeking the possible political motives of Mr. Hodgkinson, who was shot and killed by police, officials say. Senator Sanders, in a statement, said he was “sickened by this despicable act,” condemning the action “in the strongest possible terms” and saying any violence “runs against our most deeply held American values.”

On Wednesday, members of both parties began to call for a more civilized discourse, uniting around “their common humanity and American-ness,” as the Monitor reported. Part of the role of the hard-to-define “mainstream” media is to preserve those values, leaving the fringes to the fringes.

“Hearing about these kinds of views on both the right and on the left is one thing,” says Professor Zaino. “Having them seep their way into the White House is, quite frankly, another thing. And if these left-wing conspiracies are moving their way up, that is also a concern.”

“So to me, this is about an absence of leadership,” she continues. “It is up to the nation’s leaders to provide such moral leadership, to speak out against the kinds of views Jones promotes, and not support those who violate our sense of decency,” she continues, acknowledging the pain it causes the Sandy Hook parents.

“We are who we are, and we tend to believe in all sorts of possible conspiracies, but you depend on leadership in a democracy to provide a pathway to guide you, and a press to describe the contexts on these paths,” she says.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Why politicians must play ball

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By The Monitor's Editorial Board

The remarkable civility shown by lawmakers after the shooting at a GOP baseball practice should not be lost. Civility in politics needs constant nurturing to counter the disrespect that has been rising there – and has also begun to seep into workplaces, friendships, families, and religious bodies. To uplift civic life, citizens and their elected leaders must focus more on their enduring bonds than their temporary differences. In one survey after the 2016 US presidential election, 65 percent of Americans supported the idea that civility starts with citizens – by encouraging friends, family, and colleagues to be kind. If that behavior were to become more commonplace, the type of incivility that often leads to violence would find little place to flourish.

Why politicians must play ball

The attempted killing of Republican lawmakers on a baseball field near Washington has united members of Congress in a way rarely seen in recent years. Many praised each other’s consoling responses. Others vowed to temper the rhetoric of personal attacks that may have incited the June 14 shooting. And some revived the notion of creating friendships across the aisle despite the regular verbal combat over issues.

This unusual moment of common reflection should not be lost. Civility in politics must be an active quality, one that needs constant nurturing. This can counter the disrespect rising in politics that has begun to seep into workplaces, friendships, families, and religious bodies. To uplift civic life, citizens and their elected leaders must focus more on their enduring bonds than their temporary differences over policies.

One heartening example of nurturing civility is the fact that the Congressional Baseball Game was not canceled after the shooting. For 108 years, this sport activity has been one of the few places where lawmakers of different parties could get to know each other as regular folk, building trust that might then open doors for bipartisan cooperation. Other joint activities range from a Senate prayer group to a gym that members of both parties use.

In January, the newest members of the House of Representatives signed a letter of commitment to civility – in large part to counter the ill will of the 2016 elections. The new members vowed not to disparage each other. So far they have tried to maintain that pledge.

At the state level, the National Institute for Civil Discourse has been offering courses on civility to legislators and others for a few years. In the Idaho statehouse last year, Democrats and Republicans who took the course agreed to organize social events to help them go beyond partisan labels and better understand their shared motives for public service. Several legislators asked their staff to come up with bills that could find bipartisan support.

For decades, a visible model of civility in Washington was the friendship of two Supreme Court justices, Ruth Bader Ginsburg and the late Antonin Scalia. Their close ties allowed a rapport that may have softened their differences in court rulings. “I attack ideas. I don’t attack people,” Justice Scalia told “60 Minutes.”

One reason for the success of the 1787 Constitutional Convention, according to scholar Derek Webb of Stanford Law School, was the extensive social interaction among the delegates before and during the event. “Delegates like [James] Madison and [Ben] Franklin themselves suggested that, without this foundation, the Convention may not have even been able to last a few weeks, much less four months,” he writes.

In a survey after the 2016 election by KRC Research, 65 percent of Americans supported the idea that civility starts with citizens – by encouraging friends, family, and colleagues to be kind. If that behavior were to become more commonplace, the type of incivility that often leads to violence would find little place to flourish.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Safe choices through God's direction

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By Stephen Carlson

When faced with a tough decision, it can be tempting to stick with the status quo simply because it’s familiar. And sometimes, indeed, that’s the right choice to make. But contributor Stephen Carlson points out that there’s freedom to be found from uncertainty or fear that might hamper our ability to make a right decision: We can turn to God, infinite divine Mind, for inspiration and guidance. The Bible encourages us to “trust in the Lord with all your heart, and lean not on your own understanding; in all your ways acknowledge Him, and He shall direct your paths” (Proverbs 3:5, 6, New King James Version). This is a promise for each one of us.

Safe choices through God's direction

When people talk about “playing it safe,” they may just be referring to everyday matters such as deciding to carry an umbrella when there’s only a slight possibility of rain. But there are bigger decisions in life – such as the choice of a career path – in which we may feel torn between sticking with the reliable and familiar, and moving in a new direction that seems risky.

When faced with a tough decision, it’s been helpful for me to start with a humble desire to recognize and follow God’s direction. I’ve found it important to acknowledge God as my creator, the all-wise and loving divine Mind who cares for all of us as His children. This has enabled me to see the fulfillment of a promise from the Bible’s book of Proverbs: “Trust in the Lord with all your heart, and lean not on your own understanding; in all your ways acknowledge Him, and He shall direct your paths” (3:5, 6, New King James Version).

Being receptive to the inspiration the divine Mind is imparting, and shutting out human will, is prayer that can point us to the most appropriate path. The intuitions that come from God are natural, clear-cut. They feel right. They don’t aggressively push or badger. We’re playing it safe in the highest sense when we listen for, and obey, those intuitions.

Mary Baker Eddy, who discovered Christian Science, once said: “God is the fountain of light, and He illumines one’s way when one is obedient.... Be sure that God directs your way; then hasten to follow under every circumstance” (“Miscellaneous Writings 1883-1896,” p. 117).

Christian Science points to the perpetual harmony of God’s spiritual creation, to the genuine reality of existence, including the true nature of each of us as the intelligently governed image of God, of Spirit. Prayer serves to open our thought to this deeper understanding of ourselves and to its practical expression in our daily lives.

I’ve found that seeking and following divine direction has helped me to feel safe at a deeper level and to take the appropriate path at each stage of my life.

A message of love

No makeup required

A look ahead

Thanks for joining Ken and me today. One story we’re working on for tomorrow looks at Gatlinburg, Tenn., a place where people of all political stripes have gathered to help rebuild, six months after wildfires devastated the Smoky Mountain tourist hub.

A correction: A story in the June 13 Daily ('Zero waste': A city’s push to prove that less is more) misstated the amount of trash Americans generate each year. It is 258 million tons.