- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Monitor Daily Intro for September 29, 2017

On Thursday, my colleague Yvonne Zipp laid out some ways to help the residents of Puerto Rico.

Besides facing food and water shortages – which could be alleviated by the White House’s move to waive a law limiting shipping to US ports by foreign vessels – some 3.4 million Puerto Ricans remain without electricity.

The island’s power grid was notoriously fragile even before Maria took it out. Some experts are already calling for the burying of power lines in advance of next season’s storms. Some recommend heavy investment in microgrids.

How hard is it to “build back better”?

In 2014, after a typhoon raked the Philippines, the Monitor’s Peter Ford went to Tacloban to size up the prospects of doing that there. I asked him last night for a quick follow-up.

“I talked to Prof. Pauline Eadie of Nottingham University, who has studied Tacloban since the Haiyan typhoon,” Peter said. “She says they have ‘not built back better, they have built back the same’ and, in some cases, worse.”

Utility hookups have been slow because of political squabbling. Water, for example, is controlled by a neighboring municipality under the control of a rival political party. There have been gross inefficiencies. “NGOs did not coordinate,” Peter’s source told him, “so there is a surplus of fishing boats now. They all handed them out whether needed or not.”

In Puerto Rico, success might be less about grand infrastructure projects – Google “Tren Urbano” for one that some suggest helped the island go bankrupt – than about an approach that is equitable, one that includes local input and vision.

Now to our five stories for your Friday, ones that show compromise, understanding, and respect in action.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Catalonia’s breakaway bid: the view from Basque Country

In a region that waged a decades-long struggle for the kind of independence that citizens in another Spanish region hope to vote on this Sunday, autonomy has proved to be a workable compromise.

-

Catarina Fernandes Martins Correspondent

Spain’s Catalonia aims to hold an independence referendum Sunday. It could be bumpy. Madrid has declared the vote illegal. National police have arrested Catalan leaders and confiscated ballot papers. How does that play with the country’s other breakaway population? Among Basques, who saw a 40-year armed separatist struggle, the vote sparks mixed feelings. “I tell my friends that we Basques are watching and learning with the Catalans, to do it better later,” says an activist living in Germany. But in a recent poll only 16.9 percent of Basque respondents said they seek an independent state (Catalans are more evenly divided). While Spain’s regions all enjoy some autonomy, the Basques have the most, running their tax system, for example. Catalonia’s much larger economy makes Madrid wary of giving Barcelona such control. That fuels Catalan resentment, which is rooted in a sense that Catalonia, one of Spain’s major economic engines, gives more than it gets. It also underlines the privilege that Bilbao enjoys. “Pro-independence sentiment in [Basque] society has been falling as people see the current deal works quite well,” says one observer of both regional movements. Still, other Basques maintain that bucking Madrid’s wishes would mean trouble. “They fear it could bring back the sort of violence that plagued them for years,” says an expert at King’s College London. “Basques don’t want to go through that again.”

Catalonia’s breakaway bid: the view from Basque Country

Helena Gartzia has wanted independence for the Basque region her entire life. And 10 years ago the former city councilor in the industrial city of Bilbao, along with other likeminded Basque nationalists, was in the vanguard of Spain’s restive regional communities.

Today, though, it is the Catalans who are making the running in the independence stakes, scheduling a referendum for Sunday that will ask residents in the northeastern region of 7.5 million inhabitants if they want a Catalonia free from Spanish rule.

How did their fortunes switch?

Largely, observers say, because the Basque regional government has given up on Gartzia’s dream of independence, settling for a generous chunk of autonomy instead.

The central government in Madrid and the courts have declared the Catalan vote illegal, national police have arrested Catalan leaders and confiscated millions of ballot papers, and the plebiscite threatens to plunge Spain into deep constitutional crisis.

Among Basques, who lived for 40 years through the bloody armed struggle that the separatist group ETA waged for Basque independence, the vote has sparked mixed feelings.

“I am profoundly happy thinking about what the Catalans are going to experience on Sunday, and I watch it with a healthy envy,” Ms. Gartzia says. “How I myself would love the opportunity for the same experience. Unfortunately we are light years away from what is happening in Catalonia right now.”

That is because when then-president Juan Jose Ibarretxe of the center-right Basque Nationalist Party (PNV) tried to push through a self-determination referendum in 2008, he backed down in the face of opposition from Spanish courts, which ruled that the bid was illegal.

Mr. Ibarretxe, whose party is still in power today, felt he didn’t have enough public support. One poll this summer by the University of Deusto in Bilbao found that only 16.9 percent of respondents said they seek an independent state.

But Arkaitz Fullaondo, a sociologist at the University of the Basque Country, says that support, which has oscillated but not risen beyond 30 percent in recent years, reflects political leaders’ positions. The PNV has left “independence wishes in the past,” he says. “They say independence is just a dream that leads nowhere. But the fact is that the number of pro-independence voters increases when there are political movements that show independence is possible.”

The PNV stance has angered separatists who say it is taking the easy route. “If you belong to a state that doesn’t want to recognize you, and you contest this, there is going to be a moment of confrontation, which is what is happening in Catalonia,” says Garztia, who served as a city councilor with EH Bildu, the more radical and leftist independent party in the Basque Country. She says if the PNV had dared to risk such a confrontation in 2008, “we would be much closer than even the Catalans are” to an independent state.

Divided in Catalonia

Catalans, who like the Basques boast a distinct language and culture, are currently evenly divided over the independence issue, but support for the idea was not always that high. The mood shifted with the international debt crisis, which heightened a sense that Catalonia, one of Spain’s major economic engines, gives more than it gets.

Pro-independence fervor gathered new momentum in 2010, when Spain’s constitutional court watered down powers that the region sought under a new autonomy statute.

Since then Barcelona, the capital of Catalonia, and Madrid have dug in their heels as the stakes have risen.

Defying Madrid’s ban on the referendum, Catalan President Carles Puigdemont has pledged to carry out his central election promise no matter how high the cost.

That kind of talk stirs uneasy memories in the Basque region, where nearly 800 people died during ETA’s long fight for independence. The group declared a cease-fire in 2011, but it disarmed officially only in April this year. ETA members convicted of terrorist offenses remain in jail, dividing society.

“There are still all of these issues that need to be resolved post-ETA,” says Caroline Gray, an expert on Basque and Catalan independence movements at Aston University in Britain. “The remnants of violence put off a lot of citizens from thinking about independence. There is still that post-terrorism, post-conflict resolution going on.”

And many Basques – unlike Catalans – feel simply that they are getting a good deal from Madrid today. While Spain’s regions all enjoy varying degrees of autonomy, the Basques have the most, running their tax system, for example.

The size of Catalonia’s economy – nearly 20 percent of Spanish GDP compared to the Basque region’s 6 percent – makes Madrid wary of giving Barcelona control of tax revenues that are currently shared throughout Spain. That fuels Catalan resentment, but it underlines the privilege that Bilbao enjoys.

“Pro-independence sentiment in [Basque] society has been falling as people see the current deal works quite well,” says Dr. Gray. “There is not that same sense of angst.”

The de facto approach

Indeed, many Basques feel that they already have de facto independence, and some outsiders agree with them.

Bea Pereyro, for example, a doctor, is not Basque and cannot speak the local language, so she cannot work in the region. She was obliged to move to neighboring Cantabria with her husband, Ibai Herval, a former Basque paralympic swimmer representing Spain.

“I would say the Basques and the Catalans already have their independence in a way,” says Dr. Pereyro, “because of the language barrier and the difficulty other Spaniards feel when trying to access some jobs without speaking those languages or holding diplomas in those languages.”

That is not enough for Basque independence activists like Ibon Alkorta, a TV editor who lives in Germany. “I tell my friends that we Basques are watching and learning with the Catalans, to do it better later,” he says. “It’s a good test for us.”

Others worry that a referendum against Madrid’s wishes would mean only trouble. “They fear it could bring back the sort of violence that plagued them for years,” says Ramon Pacheco Pardo, an expert in international relations at King’s College in London. “Basques don’t want to go through that again."

Either way, says Gray, “the Basque issue is still very much there.”

Catarina Fernandes Martins reported from Lisbon.

Share this article

Link copied.

The Redirect

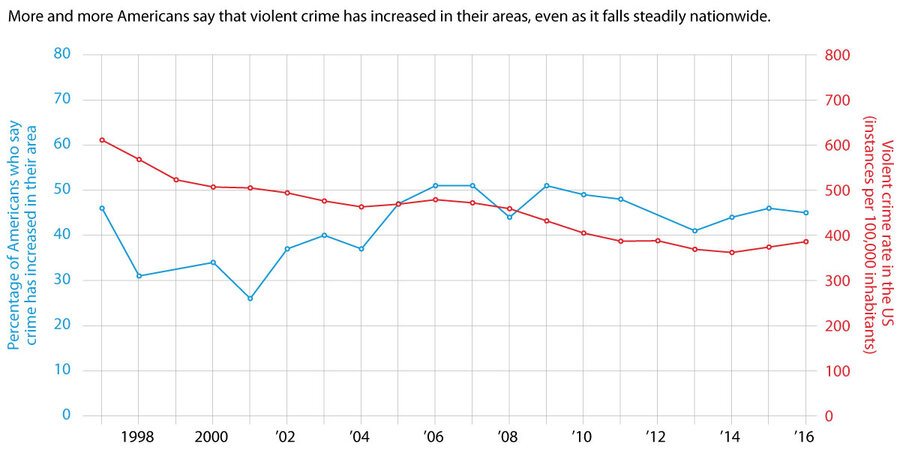

'Paradox of fear': Crime is down, but many Americans don't feel safe

Some high-profile cases and elevated rhetoric – think “American carnage” – sway Americans’ collective perception. This story looks at why incidents of violent crime may be more of an anomaly than part of a wave.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

It’s a conundrum: While US neighborhoods, as a whole, are safer than at any time in the past 25 years, many Americans remain convinced that crime is a growing problem. Part of people’s outlook depends on where they are viewing from: Rural Americans are more likely to believe the narrative of big crime in the big city. One of them is Trump voter Skip Dempsey, of Social Circle, Ga. From his rural perch, Atlanta reminds him of a “Blade Runner”-like no-man’s-land where “blood runs in the streets.” Urban residents, meanwhile, who see firsthand children riding their bikes through formerly high-crime neighborhoods, are more likely to be aware of the gains. Also playing into the question of perception versus reality, experts say, is our polarized worldviews and how those can be influenced by Hollywood, the media, and politicians. Economic uncertainty, political unrest, and a lack of civility also erode people’s feelings of safety. “The reason people so easily embrace this idea that things are bad out there … is because there is a level of discord. If we were all getting along and not distrusting our neighbor, we wouldn’t be so easily persuaded ... into thinking that the sky is falling,” says criminologist James Alan Fox.

'Paradox of fear': Crime is down, but many Americans don't feel safe

As recently as five years ago, says Urban Pie pizza shop owner Lisa Curtis, crime was so bad in her Atlanta neighborhood that newly planted rose bushes would get dug up and carted away by thieves.

So when a succession of gunshots rang out in late August, leaving a local rapper dead near her restaurant door, the scene could well have served as evidence of the growing “American carnage” described by President Trump amid a rise in violent crime in some US cities in 2015 and 2016.

Yet where such criminal mayhem may have once been routine here on Atlanta’s urban east side, today it is an anomaly. The Zone 6 precinct has become the city’s most peaceful corner, according to an Atlanta Police Department analysis, when it comes to theft and violent crime. That's partly due to an influx of wealthier residents, more effective police crime-fighting strategies, improving schools, and a blossoming local economy that benefits a wide swath of Atlantans.

“Nothing changed, nobody is staying in and locking their doors,” says Ms. Curtis. “Everybody knows that this is about a few people – the same ones who keep shooting each other and getting shot. If anything, [the restaurant has] been busier as people have come out to show support.”

To some observers, the killing of Jibril Abdur-Rahman and the neighborhood’s shocked but measured reaction can be seen as part of a shifting “paradox of fear” in America.

On one hand, people became 62 percent less likely to become the victim of a violent crime between 1993 and 2014. The number of violent-crime victims per 1,000 persons age 12 or older dropped from 29.3 to just 11.1 in that period, according to Bureau of Justice Statistics.

And so far, 2017 is on track to have the second-lowest violent crime rate of any year since 1990, according to figures released this month by the nonpartisan Brennan Center for Justice.

On the other, surveys are finding many Americans convinced that a general crime threat against law-abiding Americans is rising. That sentiment has at times found an outlet in President Trump and Attorney General Jeff Sessions, who together have painted scenes of worsening urban “war zones.”

Perception vs. reality

It’s a conundrum: While US neighborhoods, as a whole, are safer than at any time in the past 25 years, many Americans remain convinced that crime is a growing problem.

Part of people’s outlook depends on where they are viewing from: Rural Americans are far more likely to believe the narrative of big crime in the big city. One of them is Trump voter Skip Dempsey, of Social Circle, Ga. From his rural perch, Atlanta, 45 minutes to the west, reminds him of of a “Blade Runner”-like no-man’s-land where “blood runs in the streets” – and where the threat from “thugs” is constant.

Urban residents, meanwhile, who see firsthand children riding their bikes and people walking dogs at night through formerly high-crime neighborhoods, are more likely to be aware of the gains. Also playing into the question of perception versus reality, criminologists say, is our polarized worldviews and how those views can be influenced and manipulated by Hollywood, the media, and politicians. Economic uncertainty, political unrest, and a lack of civility also erode people’s feelings of safety.

“The reason people so easily embrace this idea that things are bad out there … is because there is a level of discord. If we were all getting along and not distrusting our neighbor, we wouldn’t be so easily persuaded by a short-term spike in crime into thinking that the sky is falling,” says Northeastern University criminologist James Alan Fox in Boston.

Instead, “it doesn’t matter that the homicide rate is half of what it was 25 years ago – those are just numbers,” adds Mr. Fox. “What matters is you can turn on a television set and see plenty of crime. We are saturated with crime.”

Crime is bad ... but not in my neighborhood

Yet dig deeper and criminologists and political scientists suggest that rising crime is not top of mind for political strategists nor, necessarily, US police departments, the vast majority of which are seeing the positive impacts of data-driven policing strategies.

And a large majority of Americans as a whole, at least by some measurements, feel relatively safe in their own surrounds. In findings that have been mirrored elsewhere, a Journal of General Internal Medicine study found only 8.7 percent of Americans over 50 regarded their immediate neighborhood as unsafe; 68 percent considered it “very safe.”

“People hear rhetoric about crime, they see crime on the evening news, but they know in their own minds that they are safer than they used to be,” says Ames Grawert, a counsel in the Brennan Center’s Justice Program in New York. That, he says, “is why, even if they think crime is going up in the United States, many feel like their neighborhood is safer than ever.”

In fact, he adds, “cities have been the principal beneficiary of crime declining – and that includes New York City, which now has a lower murder rate than the nation as a whole, where 20 years ago it was a dangerous city.”

To be sure, a spike in violence in Chicago, Baltimore, and Washington, D.C., drove a national murder rate increase in 2015 and 2016. But this year, the rate appears once again to be tacking downward – even in Chicago. The murder rate is projected to fall by 2.5 percent in 2017, according to the Brennan Center. If that holds true, it would be the lowest since 2009.

White House view of crime

Yet outsize crime fears clearly have had political impact in the US – and could extend to policy as the Trump administration pushes for higher mandatory minimum sentences for drug offenses and scales back ethics oversight of local police departments.

Mr. Trump earlier this year noted correctly that “the murder rate in 2015 experienced its largest single-year increase in nearly half a century.” (Criminologists point out that even with that spike, the murder rate was still well below 1990s levels.)

His statement, as well as speeches by Mr. Sessions, feed into a broader narrative of how the rise in inner-city murder rates in 2015 and 2016 were part of a longer-term trend that to some suggested America, in the Obama era, was coddling criminals while over-focusing on rogue cops and corrupt police departments.

“Trump’s approach was to make America scared again, and he did,” says Professor Fox.

Ahead of Election Day, 57 percent of respondents to a Pew survey said crime has gotten worse in the US since 2008, including 78 percent of Trump supporters and 37 percent of Hillary Clinton supporters. Meanwhile, the reality was that US violent crime fell by 19 percent between 2008 and 2015, according to the FBI.

Reasons behind the decline

At the same time, many Americans intrinsically understand that violence is being curtailed by a plethora of broader factors, some not yet fully understood, says American University criminologist Joseph Young, who studies the consequences of political violence.

“We have seen sustained economic growth and we’ve also seen a lot of inner cities invigorated and gentrified, which in turn has squeezed problems into other places,” says Professor Young. Police, he notes, have also become far more adept in mapping Big Data to target high-crime zones in near real-time, which in turn leads to better community-relations as police pay more attention to what is driving local complaints.

That suggests to some that the stoking of fears about crime is political. “If the president said this is the safest Americans have ever been – that wouldn’t get you very far politically,” says Clemson University political scientist Dave Woodard.

Some of the concern about threats in rural Trump country, at least, may be justified, though perhaps the object of their concern is misplaced. A 2013 Annals of Emergency Medicine study found that the personal risk of injury death – including violent crime and accidents – is more than 20 percent higher in the countryside than it is in large urban areas. In other words, while homicide risks remain higher in cities, people are safer in cities than in rural areas when accidents are also factored in.

In terms of the decline in crime so far this year, conservatives point out that gun crimes have declined in the US even as gun ownership and liberalized gun-carry laws have expanded. And others are quick to credit Trump’s law-and-order rhetoric for the projected downtick.

But whether the Trump administration has really driven the agenda is a far different question, says Professor Woodard. In fact, Woodard says he is consulting for a Republican statewide campaign in South Carolina, and crime has not been a top strategy topic. “I don’t sense that most of the voting populace feels like we’re in a violent period – quite the opposite,” he says.

On the policy front, two weeks ago, the Republican-led Congress balked at a Sessions plan to expand civil asset forfeiture, a controversial program that allows police to seize the assets of suspects who have not been convicted of a crime. And from state to state, one of the few areas of political bipartisanship has been around criminal justice reforms.

Georgia, a ruby-red state, has led the way by introducing strong prison diversion programs and making it easier for former convicts to get jobs and rebuild their lives.

“There’s been a growing view on the left and right since the 1990s that crime and violence aren’t problems you can … incarcerate your way out of,” says Mr. Grawert. “There’s a growing consensus that we can have a safer and freer society, with a better criminal justice system, and there are people on both sides invested in that. There are strong Republican voices like [Sen.] Chuck Grassley flatly saying, ‘Crime isn’t out of control.’ That’s a big reason why the fear-mongering rhetoric hasn’t been as successful as one might fear.”

FBI, Gallup

African architects showcase a continent’s aspirations

If “African architecture” makes you think first of leftover colonial construction, think again. A new award recognizes some of the continent’s homegrown stars.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

Africa’s architects, and their projects, are as staggeringly diverse as their continent. That diversity was on display Thursday night in Cape Town, South Africa, where the winners of the Africa Architecture Awards – the first-ever Pan-African award for building design – were announced: an airy and elegant community history museum soaring above a township in South Africa, a cultural center in rural Senegal whose thatched roof undulates like a sine wave, a Ghanaian office inspired by patterns found in the bark of a palm tree. Yet many of the designs are united by a loudly announced sense of belonging to the places they come from, and reclaiming the past from legacies of colonialism or apartheid. The prize-winning museum’s neighborhood in Durban, for example, was the site of an infamous forced removal of residents in order to resegregate the area. Much of its architecture literally crumbled beneath the apartheid government’s bulldozers. “We come from a deep history of pain and suffering, but also a history of resilience,” says Rod Choromanski, the lead architect on the project. “And we want to show people how important their lives and histories are.”

African architects showcase a continent’s aspirations

For decades, crammed neighborhoods of matchbox houses and tin shacks lined the edges of South Africa’s cities like grand human filing cabinets: places the white government could store the vast quantities of black labor it needed to keep the country going.

When these "townships" of workers – forbidden from living in the cities proper – got too crowded, too diverse, or too revolutionary, the government would often simply tear them down and start over.

Today, however, these architectural afterthoughts have become the sites of some of the country’s most creative and forward-thinking design projects – buildings that seem by their very existence to demand a new way of seeing places once confined to the margins of both South Africa’s cities and its history.

Among these projects is the airy and elegant community history museum that now soars above the township of Cato Manor in Durban, a coastal city here. And on Thursday night, the Umkhumbane Museum took the grand prize in the Africa Architecture Awards, the first ever pan-African award for building design.

“We come from a deep history of pain and suffering, but also a deep history of resilience,” says Rod Choromanski, the lead architect on the project. “And we want to show people how important their lives and histories are.”

In a wider sense, too, many of the award’s finalists embody a continent whose architects are simultaneously reclaiming a design history snuffed out – often violently – by colonialism while also creating spaces that are asserting Africa loudly in the global architecture world.

Reimagined spaces

Finalists for the main award included a cultural center in rural Senegal whose thatched roof undulates like a sine wave and a Ghanaian office building whose design was inspired by the geometrical triangular patterns found in the bark of a palm tree. The finalists capture “an incredible moment in time for pan-African architecture,” wrote Evan Lockhart-Barker, managing director of a retail business development initiative for Saint-Gobain, the construction multi-national that sponsored the awards. “The values and aspirations displayed in the awards have led to incredible insights about the continent and its shape-shifting ways,” he wrote in a form response to journalists.

To many outsiders, architecture in Africa has long been synonymous with aging colonial cities, whose crumbling art deco and modernist facades at times felt like they were copy-pasted from European capitals. In many countries, indeed, colonial conquest had wiped out much of the existing architecture to make way for Western-style cities and towns. But even in those spaces, Africans have always innovated, often designing new spaces for themselves in the relics of old ones. In Johannesburg, for instance, one of the city’s main synagogues is now a popular Pentecostal church, where below the delicate Hebrew etchings on its stone gates hawkers now sell cell phones and sandwiches to congregants and passerby.

African architecture, meanwhile, has become increasingly prominent globally in recent decades. Like the continent they come from, Africa’s architects – and their projects – are staggeringly diverse, but many are united by a loudly announced sense of belonging to the places they come from.

One of the finalists for the architectural awards this year, for instance, was an “adventure playground” in Addis Ababa designed by two Ethiopian architects, which incorporates local materials like bamboo, recycled tires, jerry cans, and satellite dishes. Another, the Senegalese cultural center, was built only using entirely local construction techniques.

'A new vision of this country'

Though a number of the projects in this year’s awards were produced by architecture firms outside the continent, African architects say their voices – and their ideas – are shaping the continent’s design future.

“We do have an African architecture, but sometimes we feel we don’t have the vocabulary yet to describe what it is,” says Ogundare Olawale Israel, a graduate student at the University of Johannesburg’s school of architecture and the winner of this year’s “emerging voices” prize.

For many African architects, the language their work speaks is deeply personal. Mr. Choromanski, for instance, comes from a mixed-race family in Durban who were forcibly separated by apartheid’s racial laws. Some of the family were classified as white, while others, including him, were labeled “coloured,” a term for mixed-race people. That label allowed them to be denied access to the city’s nicest schools, hospitals, and neighborhoods.

Similarly, the vibrantly multiracial Durban neighborhood of Cato Manor – where the Umkhumbane Museum is located – was the site of an infamous forced removal of its residents in the 1950s and ‘60s in order to re-segregate the area. Much of the neighborhood’s architecture literally crumbled beneath the apartheid government’s bulldozers.

The new museum, which was finished last year but has not yet opened to the public, holds exhibits on the area’s history, as well the history of the Zulu people. The mother of the current Zulu king was recently reburied in the space, further adding to its significance for residents.

“Sometimes I think of the 1980s, when I was sitting in a classroom studying architecture while the country was burning, while Mandela was locked in prison,” Choromanski says. “People were fighting for a new vision of this country, and the architecture can be part of that.”

In Rome, a tangible sign of a ‘rewilding’ Europe

In the place where legend has it that Romulus was suckled by a she-wolf, wolves now roam again. And as in the American West, the return of these animals is forcing a rethink about the interplay of humans and other species.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

For the first time in more than 100 years, wolves have returned to Rome. Their reappearance is emblematic of the species’ remarkable resurgence across Europe following centuries of persecution, a saga that parallels the tale of gray wolves in the American West. Hunting, trapping, and poisoning drove Italy’s wolves to the brink of extinction before they were granted protected status in 1971. The population has since rebounded. The recovery of Canis lupus is due not only to bans on hunting and strict protection measures but also to the gradual “rewilding” of large parts of Europe, as smallholders have abandoned unprofitable farms. Italy, for instance, now has twice as much forest and woodland as it did at the end of World War II. Farmers often see wolves as a threat to their livestock, but conservationists argue that their return can help restore balance to the environment, keeping in check the numbers of deer and wild boar. As one natural sciences professor says: “We’re very happy that they’re back.”

In Rome, a tangible sign of a ‘rewilding’ Europe

It is one of the world’s best-known founding fables: According to legend, Rome was founded by Romulus, who as a baby was suckled along with his brother Remus by a she-wolf, after they were abandoned in the wilderness.

Now, nearly 3,000 years after Romulus killed his brother and became the first king of Rome, wild wolves are back. A small pack has been discovered living in the countryside just outside the city’s busy six-lane ring road and not far from Leonardo da Vinci International Airport.

It is the first time in more than a hundred years that wolves have established a presence near Rome, experts say. Their reappearance is emblematic of the species’ remarkable resurgence across Europe following centuries of persecution, a saga that parallels the tale of gray wolves across the Atlantic in the American West.

The pack consists of two adults and at least two mature cubs, according to the Italian League for the Protection of Birds, which runs a nature reserve where the animals have taken up residence.

They have been photographed by trap cameras drinking from muddy waterholes and loping along sandy woodland tracks.

The cubs were born this year, the conservation organization said, calling the presence of wolves just outside Rome “extraordinary news.”

The wolves mostly confine themselves to an inaccessible area of dense scrub and woodland, the League said.

“We are honored to have in this nature reserve such an emblematic species, which even today is subject to hunting and intolerance,” says Fulvio Mamone Capria, the president of the conservation group.

“Their presence is highly symbolic, both for Rome and the entire country.”

Not everyone is happy...

Hunting, trapping, and poisoning drove Italy’s wolves to the brink of extinction before they were granted protected status in 1971.

The population has since rebounded, and there are now estimated to be 1,500-2,000 individuals roaming the country, with strong populations in the Apennine Mountain range and in the Alps.

The wolves don’t always receive a warm welcome, as is often the case when apex predators return to regions where they are likely to come into contact with humans and their livestock. Every few months an Italian landowner, angry at having lost livestock to lupine jaws, will shoot a wolf and dump its corpse by the roadside – sometimes mutilated or decapitated – in protest against government policy.

Earlier this year Italian regional governments debated introducing a limited cull of wolves. It would have been the first such licensed killing for 46 years but it was fiercely opposed by conservation groups; 200,000 people signed a petition against the cull and the plan was dropped.

It is not just in Italy that wolves are on the increase. Some packs have crossed the Alps and entered France, where shepherds complain that they kill sheep.

Having crossed the border from Italy in 1992, they have since spread through the Jura and Vosges mountains on France’s eastern border into the Massif Central. Biologists now believe that at least one wolf is living in the forest of Rambouillet outside Paris.

Wolves returned to Switzerland in 1995 and to Denmark in 2012 – the first time they had been detected in the country since the time of Napoleon.

In Spain, the once-rare Iberian wolf, a subspecies, has recovered from near extinction in the mid-20th century and now numbers around 2,500.

Europe's countryside: fewer people, more wolves

The recovery of Canis lupus is due not only to bans on hunting and strict protection measures but also to the gradual “rewilding” of large parts of Europe.

As farmers across the continent have abandoned economically unproductive small farms and sought easier lives in towns, large tracts of countryside have reverted to woodland, creating new habitat for big animals.

Italy, for instance, now has twice as much forest and woodland as it did at the end of World War II; 35 percent of the country is covered in trees.

While farmers may see wolves as a threat to their livestock, conservationists argue that their return can help restore balance to the environment, keeping in check the numbers of deer and wild boar.

Rewilding Europe, a conservation movement founded in 2011 that works throughout the continent, aims to restore a million hectares of land to a natural state by 2022.

The organization would like to see wild horses – of the type seen in prehistoric cave drawings in France and Spain – as well as European bison and ibex reintroduced to areas they once inhabited.

Rewilding Europe maintains that the presence of big mammals would encourage eco-tourism and help people in parts of Europe that suffer from high unemployment.

Back in Rome, experts say the small wolf pack poses virtually no threat to humans.

Nor are the wolves a menace to livestock on surrounding farms – analysis of their excrement has shown that their diet is made up exclusively of wild boar, which roam the countryside around the capital in ever-increasing numbers.

It is thought that the wolves arrived near the capital after moving south from an area around Lake Bracciano, 30 miles away, where a small but resilient wolf population has existed for decades.

“From the scientific literature, we know that it’s the first time in more than 100 years that wolves have been found living near Rome,” says Alessia De Lorenzis, a professor of natural sciences who is monitoring the wolf pack in the Castel di Guido protected reserve. “We’re very happy that they’re back.”

On Film

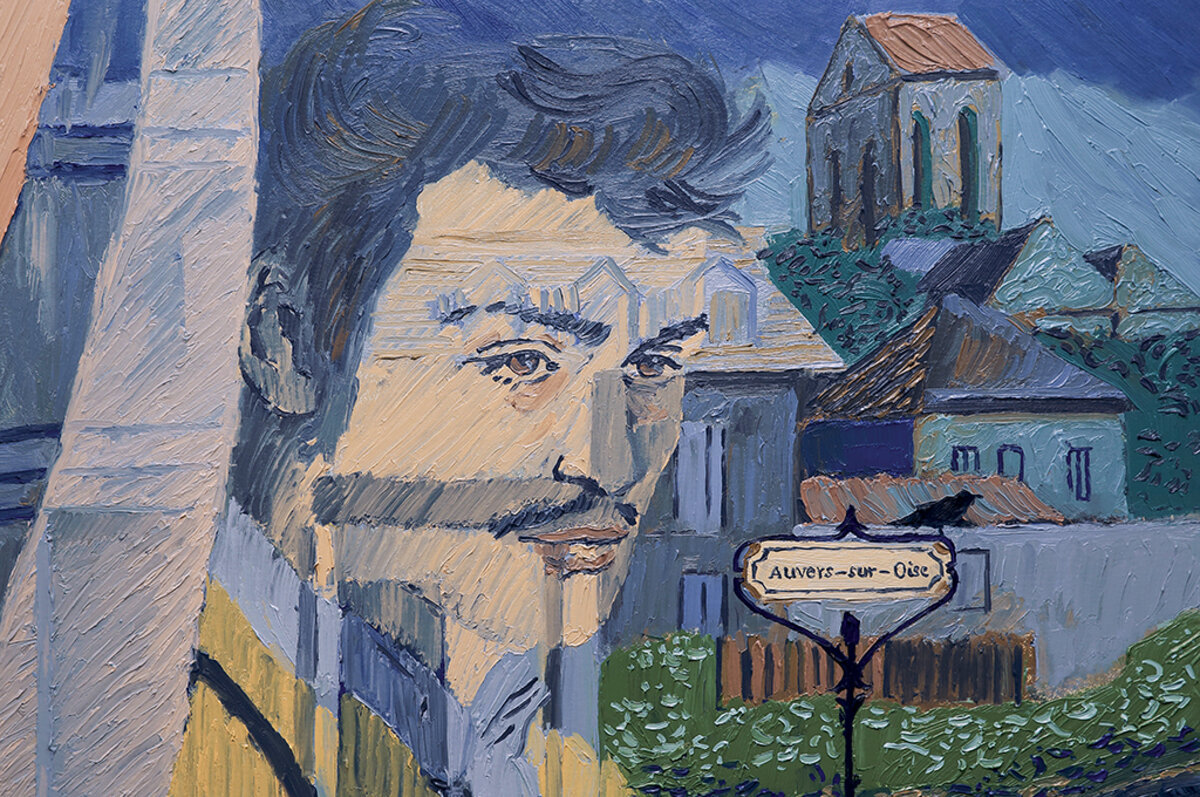

‘Loving Vincent’: a big-screen tribute, painted by hand

Had the creators of this tribute to a Dutch master possessed today’s technology when they began their work seven years ago, we’d have all missed out on this cinematic work of art. Peter Rainer looks beyond the brushwork.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By Peter Rainer Film critic

“Loving Vincent” is framed as a kind of “Citizen Kane”-style detective story focusing on Vincent van Gogh’s frenzied final months in Auvers-sur-Oise, France, where, in 1890, he fatally shot himself. (The film’s title is derived from Van Gogh’s signoffs to his beloved brother in his letters – “Your loving Vincent.”) The film took seven years to complete and involved 125 artists hand-painting some 65,000 frames of film. About 130 of Van Gogh’s paintings are dynamically reproduced in the flow of images using this method, in which everything is first filmed as live-action and then rotoscoped with animation. What exactly are we getting with this vast swirl of colorations? It’s kind of kicky to pick out all the paintings as the story ensues: “Starry Night,” and many others. But in the end, the reproductions can’t possibly match the originals’ emotional fervor. How could they? Still, the fact that this movie was even attempted is daunting. It’s the kind of folly that demands a measure of respect for the effort, if not altogether for the result.

‘Loving Vincent’: a big-screen tribute, painted by hand

“Loving Vincent” is billed as “the world’s first fully painted feature film,” and I have no reason to doubt the claim. The Vincent in the title of this very strange movie is the great Dutch artist Vincent van Gogh, and you would think he already had more than his share of biopics.

The most famous, of course, is Vincente Minnelli’s very fine “Lust for Life,” starring Kirk Douglas in one of his best seething performances. Maurice Pialat’s “Van Gogh” has its adherents, as does Paul Cox’s “Vincent,” which makes great use of the painter’s canvases and letters to his brother and benefactor Theo. There’s also Akira Kurosawa’s “Dreams,” featuring a segment with Martin Scorsese as Van Gogh – still my favorite piece of miscasting in all of cinema.

Best, perhaps, is Robert Altman’s rarely seen “Vincent & Theo,” starring Tim Roth as Van Gogh, one of the very few movies that demonstrates, without any romanticizing, the ferment that can underlie great artistry. It has some of the same tumultuous emotionality as Van Gogh’s paintings.

“Loving Vincent,” co-directed by Hugh Welchman and Polish animator Dorota Kobiela and co-scripted by Jacek Dehnel, is framed as a kind of “Citizen Kane”-style detective story focusing on Van Gogh’s frenzied final months in Auvers-sur-Oise, France, where, in 1890, he fatally shot himself. (The film’s title is derived from Van Gogh’s signoffs to his beloved brother in his letters – “Your loving Vincent.”)

Before we get into the substance of the film, attention must be paid to how its imagery came to be. (In a sense, style and substance in this movie are synonymous.) I always feel a little guilty about criticizing animated features because the painstaking work that goes into creating even a bad animated movie is so often staggering. “Loving Vincent” took seven years to complete and involved 125 artists hand-painting some 65,000 frames of film. About 130 of Van Gogh’s paintings are dynamically reproduced in the flow of images using this method, in which everything is first filmed as live-action and then rotoscoped with animation.

The scenario, if not the imagery, is fairly straightforward. Upon hearing the news of Vincent’s death, Armand Roulin (voiced by Douglas Booth), at the request of his postmaster father, Joseph (Chris O’Dowd), is tasked with delivering the last letter from Vincent (the Polish theater actor Robert Gulaczyk) to Theo. Armand reluctantly complies, only to discover that Theo, too, has died. He decides to stay in Auvers-sur-Oise and uncover what really happened to Van Gogh in the end. (Armand also acts as the film’s narrator.) In the course of his detective work, he encounters various villagers who all seem to have their own theories about the artist’s demise. Some even believe he was murdered. (This theory was actually put forth, without any definitive proof, in a celebrated recent biography by Gregory White Smith and Steven Naifeh.) As the townspeople take turns offering up their version of events, we recognize some of their faces from Van Gogh’s famous portraits, including Marguerite Gachet (Saoirse Ronan) and her father, Dr. Paul Gachet (Jerome Flynn), who treated Van Gogh in his last days.

The filmmakers resort to multiple flashbacks of Van Gogh’s life, which, unlike the present-day imagery, are exclusively in black and white – a mistake, I think, because the grayed-out effect drags down the look of the entire film, which is otherwise almost riotous with color.

But what exactly are we getting with this vast swirl of colorations, these 65,000 frames of rotoscoped reproductions? It’s kind of kicky to pick out all the paintings as the story ensues: “The Night Café,” “Wheatfield with Crows,” “Starry Night,” and many others. But in the end, we are viewing, at best, deft – and at worst, kitschy – renderings of great paintings. The reproductions can’t possibly match the originals’ emotional fervor. How could they?

There’s another problem here, which is especially typical of movies about great, tortured artists. The filmmakers want us to understand Van Gogh’s mind through his work, and while this approach certainly has its pop psych fascinations, it’s ultimately too glib. The correlation between how an artist lives his life, and the work he produces in that life, is too complicated, perhaps too unknowable, for such one-to-one connections.

Still, the fact that this movie, with its 65,000 painted frames, was even attempted, is daunting. It’s the kind of folly that demands a measure of respect, for the effort, if not altogether for the result. Grade: B- (Rated PG-13 (for mature thematic elements, some violence, sexual material, and smoking).

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

The start-ups in an upstart US economy

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By The Monitor's Editorial Board

The United States has moved up to second – behind Switzerland – in the Global Competitiveness Index. The main reason: Americans have maintained a “vibrant innovation ecosystem.” Can that be sustained? Making the economy safe for innovation and entrepreneurship is no easy task, especially as conditions can rapidly change. But the report notes one global trend: “During the last decade,” it found, “the nature of innovation has shifted: From being driven by individuals working within the well-defined boundaries of corporate or university labs, innovation increasingly emerges from the distributed intelligence of a global crowd.” New ideas, in other words, are flowing more easily. If would-be entrepreneurs can have easy access to capital – such as crowdsourcing – they may be less fearful about launching a business. Countries that have grown the most since the world financial crisis a decade ago have largely done so by removing barriers for entrepreneurs, with the biggest barrier being fear of failure.

The start-ups in an upstart US economy

Since the end of the Great Recession in 2009, the United States has not only enjoyed a steady economic recovery, it has also improved on many key measures that drive future prosperity. That fact is reflected in its position on the Global Competitiveness Index. The US went from third to second this year, coming in just behind Switzerland.

The main reason for this progress is that Americans have maintained a “vibrant innovation ecosystem” that helps improve worker productivity, according to the World Economic Forum, which publishes the Global Competitiveness Report with country rankings.

Just how to maintain that vibrancy is the background for many debates about the US economy today. How should Congress reform taxes? Which cities will win Amazon’s second headquarters? Will electric vehicles or driverless cars create more jobs? Amid such debates, it is easy to forget the underlying strengths of the US economy.

It is No. 1 in how it finances entrepreneurs, for example. It has the world’s most sophisticated consumers. And it ranks second in its capacity for research and its availability of scientists and engineers. In its report, the World Economic Forum also cites the US for its strength in “efficiency enhancers.”

“Efficiency” is another way of saying that the US, like many other countries, has been able to reduce the fear of starting a business or inventing a product or service. Economists like to chart whether a nation’s culture, or its system of values, has a certain “tightness” that discourages risk-taking. American culture is rather “loose” in being open to go-getters. Its upstarts led to more start-ups.

Yet making the economy safe for innovation and entrepreneurship is no easy task, especially as conditions can rapidly change. The report notes one global trend: “During the last decade, the nature of innovation has shifted: From being driven by individuals working within the well-defined boundaries of corporate or university labs, innovation increasingly emerges from the distributed intelligence of a global crowd.”

New ideas for business, in other words, are flowing more easily across borders and between individuals. If would-be entrepreneurs can have easy access to capital – such as crowdsourcing – they may be less fearful about launching a business. A survey last May found that half of Millennials in the US plan to start a business in the next three years. And according to The Economist magazine, a forthcoming report from the Kauffman Foundation finds that “high-growth entrepreneurship has rebounded in America from the trough induced by the global financial crisis....”

Countries that have grown the most since the world financial crisis a decade ago have largely done so by removing barriers for entrepreneurs, with the biggest barrier being fear of failure. Those nations with a vibrant “ecosystem” for innovation have the most to offer entrepreneurs. They also have the most to gain in global competitiveness.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Deeds of love

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By Laura Clayton

Have you ever been touched by some act of lovingkindness so pure and genuine, so heartfelt and unselfish, that no words could describe its effect on you? Millions of such acts go on each day, hidden from the world, done quietly, persistently, and sometimes at great personal cost or risk to those doing them. Such acts are rooted in the understanding, even in a small degree, that pure love underlies our very reason for existing. To love is to live, in a sense. Our lives are measured more by what we do than by what we say, and rise in the degree that we subordinate self-interest to the interests of others. Such love is the reflection of divine Love, God.

Deeds of love

Have you ever been touched by some act of lovingkindness so pure and genuine, so heartfelt and unselfish, that no words could describe its effect on you? I have. Millions of such acts go on each day, hidden from the world, done quietly, persistently, and sometimes at great personal cost or risk to those doing them.

Such acts are rooted in the understanding, even in a small degree, that pure love underlies our very reason for existing. To love is to live, in a sense. Our lives are measured more by what we do than by what we say, and rise in the degree that we subordinate self-interest to the interests of others. Such love is spiritual, the reflection of divine Love. Christian Science brings out that divine Love is our Father-Mother God, who has created us in His image, to express Love’s eternal goodness (see Genesis 1:26, 27, 31). Wherever hatred, callousness, or indifference arises, whether in speech or deed, it’s clear that a kind of blindness to the nature of God as Love has imposed itself on someone’s thinking. But the light of the true idea of God, the Christ, can dispel that blindness through spiritual understanding and spiritual love, which find expression in healing and tangible deeds of compassion.

One of the most profound and inspiring statements on the need for love to be expressed in heartfelt deeds was made by a man who had previously indulged in hatred and violence against a new religious sect springing up in ancient Israel. He was Saul of Tarsus – a brilliant Jewish scholar and lawyer who participated in ruthless assaults against the followers of Christ Jesus, after he had been crucified. And yet, one day, quite suddenly, Saul experienced a dramatic conversion. Temporarily blinded, he found shelter and eventual healing of his blindness from the very people he had been trying to destroy. Remarkably, he went on to become a great healer and Christian leader.

In his brief essay on the subject of “charity,” or spiritual love toward mankind, which has touched millions through the centuries, Saul, whose spiritual transformation earned him the new name Paul, establishes the ascendancy of genuine love over mere words or showy displays:

Though I speak with the tongues of men and of angels, and have not charity, I am become as sounding brass, or a tinkling cymbal.... And though I bestow all my goods to feed the poor, and though I give my body to be burned, and have not charity, it profiteth me nothing. Charity suffereth long, and is kind; charity envieth not; charity vaunteth not itself, is not puffed up, doth not behave itself unseemly, seeketh not her own, is not easily provoked, thinketh no evil; rejoiceth not in iniquity, but rejoiceth in the truth; beareth all things, believeth all things, hopeth all things, endureth all things. Charity never faileth ... (I Corinthians 13:1, 3-8)

To express even a few of these characteristics of love toward others may seem like a tall order. But I find it encouraging to remember that deeds of compassion and kindness in the lives of many noble individuals have sprung up, phoenixlike, from the ashes of falsehood and ignorance. And in moments of prayer, when I’ve been especially clear that the love I express originates not in me, but in divine Love, my true spiritual source, it’s as though a veil is lifted from my eyes, so to speak, and I glimpse something of divine Love motivating me and working through my actions. I’ve seen the love that “never faileth” heal what appeared to be a crushing sense of grief or loss – and I’ve also seen it evaporate hatred and ill health. Hatred and discord simply can’t abide within the atmosphere of infinite Love, the all-present and all-powerful divine Spirit, or God. The discoverer of Christian Science, Mary Baker Eddy, once wrote: “Heaven’s signet is Love. We need it to stamp our religions and to spiritualize thought, motive, and endeavor” (“Christian Healing,” p. 19).

Like Paul, we can yield to Christ, the true idea of Love, and awaken to a greater clarity of purpose and a desire to love more unselfishly. And we’ll feel pushed by Christ to go beyond words – to better deeds of love. That’s genuine living.

A message of love

From Tehran to the Caspian

A look ahead

Thanks for joining us today. Come back Monday. At the start of the US Supreme Court’s new term, we’ll be looking at how President Trump’s shaping of the judiciary will begin to be felt on issues from the travel ban and religious freedom to partisan gerrymandering and public-sector unions.