In a coincidence that some might call Halloween-eerie, Wall Street reached two milestones this week:

• On Wednesday, the widely watched Dow Jones Industrial Average surpassed 23,000 points for the first time, the third-fastest rise of 1,000 points amid the second-longest bull run in its history.

• On Thursday, US investors marked the 30-year anniversary of the worst one-day collapse in the Dow’s history, when the stock market in a single session lost more than a quarter of its value.

Market analysts used the second milestone as a warning to investors enthralled with the first. Don’t get so self-assured about the good times, they warned, that you don’t prepare for the bad times. Only twice before have US stock valuations been higher in relation to their earnings: in 1929, right before the market crash, and 2000, right before the popping of the dot-com bubble.

But the call for alertness might apply not just to investors but also to developed nations, especially the United States.

At the moment, things look sunny. Underlying Wall Street’s frothy records is a global economic boom that is remarkably synchronized. Almost everywhere in the world – even in economic basket cases such as Brazil and Russia – growth is picking up. Inflation is tame in most places, allowing central banks to keep interest rates low. Economic crises are relatively few.

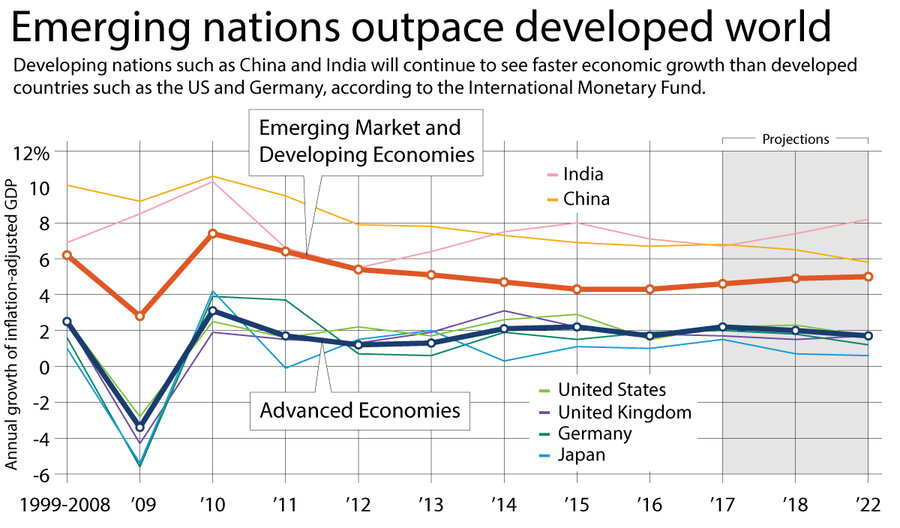

But unlike the long boom before the Great Recession, most of that growth is happening not in the developed world but in emerging markets.

“We have gotten complacent when it comes to competitiveness,” says Rob Atkinson, president of the Information Technology & Innovation Foundation (ITIF), a Washington think tank.

Growth in US workplace productivity, a key enabler of rising wages and living standards, is rising only slowly by official measures. The progress in emerging markets isn’t being matched by much oomph in America, Europe, or Japan.

“The pendulum of world economic growth has swung dramatically from the so-called advanced countries to the emerging and developing economies,” Stephen Roach, senior fellow at Yale University’s Jackson Institute of Global Affairs, wrote in May. “New? Absolutely. Normal? Not even close. It is a stunning development.”

From 1980 to 2007, the United States and other advanced economies represented 59 percent of the world’s economic pie (output, adjusted for the purchasing power parity of currencies) while the emerging markets owned the other 41 percent, he points out. By next year, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) forecasts that those shares will have reversed: 41 percent for the developed world, 59 percent for the emerging markets.

This shift has had enormous economic consequences in many nations that have adopted pro-growth policies. In India, high growth has cut the rate of extreme poverty from 50 percent in 1994 to less than 20 percent today. In Vietnam, the rate has fallen from 64 percent to less than 3 percent during a similar period.

Income inequality is growing for populations within many nations, yet it is falling meaningfully on a global scale.

And this shift is taking place even though the growth of foreign trade has slowed by more than half since the 1999-2008 period, according to the IMF.

While developed nations are growing slowly, emerging nations are finding ways to grow faster in ways other than simply boosting exports. Their outperformance is expected to continue.

The IMF forecasts emerging markets will grow 4.6 percent this year and reach about 5 percent over the medium term. Growth for the developed economies is forecast at less than half that.

“Near-term risks are broadly balanced,” the IMF’s steering committee said on Saturday, “but there is no room for complacency.”

The idea keeps popping up.

“The upturn is promising, but there is no room for complacency,” Catherine Mann, chief economist of the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), said a month earlier.

What these economists mean by complacency is nations’ potential failure to take advantage of the good times to enact policies to support stronger growth and financial stability.

Take tax reform. This summer India passed what is being billed as its biggest tax change ever, replacing its provincial taxes with a single national one. The change is so disruptive that the OECD has downgraded its growth forecast for India this year, although the new tax structure should boost the nation’s investment and productivity in the long run.

Even Britain, one of the few nations whose growth is expected to slow next year, has lowered its corporate tax rate and expanded tax credits for research and development.

In the US, by contrast, broad tax reform looks uncertain as the Trump administration and the Republican Congress have so far failed to find consensus on what reform would look like. And with Republicans talking about tax cuts that are financed by adding to the nation's debt, economists worry that even a legislative success may not improve the nation's economic health.

Mr. Atkinson worries, moreover, that the US is ignoring deeper fundamentals of growth. In the 1980s, scared by the gains by Japan and Germany, the US got behind legislative and public and private efforts to boost productivity. Now, America’s slow productivity growth is virtually ignored by the press, he says.

Some observers say it’s not just a challenge for policymakers and deep-pocketed financiers.

“These days Americans are less likely to switch jobs, less likely to move around the country, and, on a given day, less likely to outside the house at all,” writes Tyler Cowen, an economist at George Mason University and author of the 2017 book, “The Complacent Class: The Self-Defeating Quest for the American Dream.” Decisions to preserve our status quo “have made us more risk averse and more set in our ways, more segregated, and they have sapped us of the pioneer spirit that made America the world’s most productive and innovative economy.”

Other economists agree, pointing to a “new normal,” where, despite the optimism on Wall Street, the US is poised to enter a period of slow growth and slowing innovation.

But innovation and its economic impact are notoriously hard to predict. The personal computer revolution, for example, launched in the 1980s but didn’t boost US productivity until 1995. In a report last year, Accenture forecast that the integration of artificial intelligence and related technologies could double the annual economic growth rates of developed nations by 2035.

Of the 12 countries it looked at, the global services company found that a leading beneficiary would be the US, which would see annual growth jump from 2.6 percent to 4.6 percent per year thanks to the new technology.

“We are between those waves” of technological impact, says Mr. Atkinson of the ITIF. “Self-driving cars, robotics, AI [artificial intelligence] … maybe 2025, 2030, you will see these things really begin to have bite.”