The ultra-sleek bullet train, floating on a magnetic cushion, accelerates as it leaves Shanghai’s Pudong International Airport for the megacity of 24 million people. Outside, a futuristic metropolis unfolds. Curved skyscrapers and raised freeways flash by until they blur. Inside the car, green digits above the doorway shoot upward: 200 kilometers per hour ... 300 ... 431.

The car is uncrowded, its well-dressed passengers unimpressed by the world’s fastest commercial train. Some riders stare at mobile phones. No one speaks. Less than eight minutes later, the train glides to a stop and passengers alight, stepping past stewards wearing long coats into a high-ceilinged station.

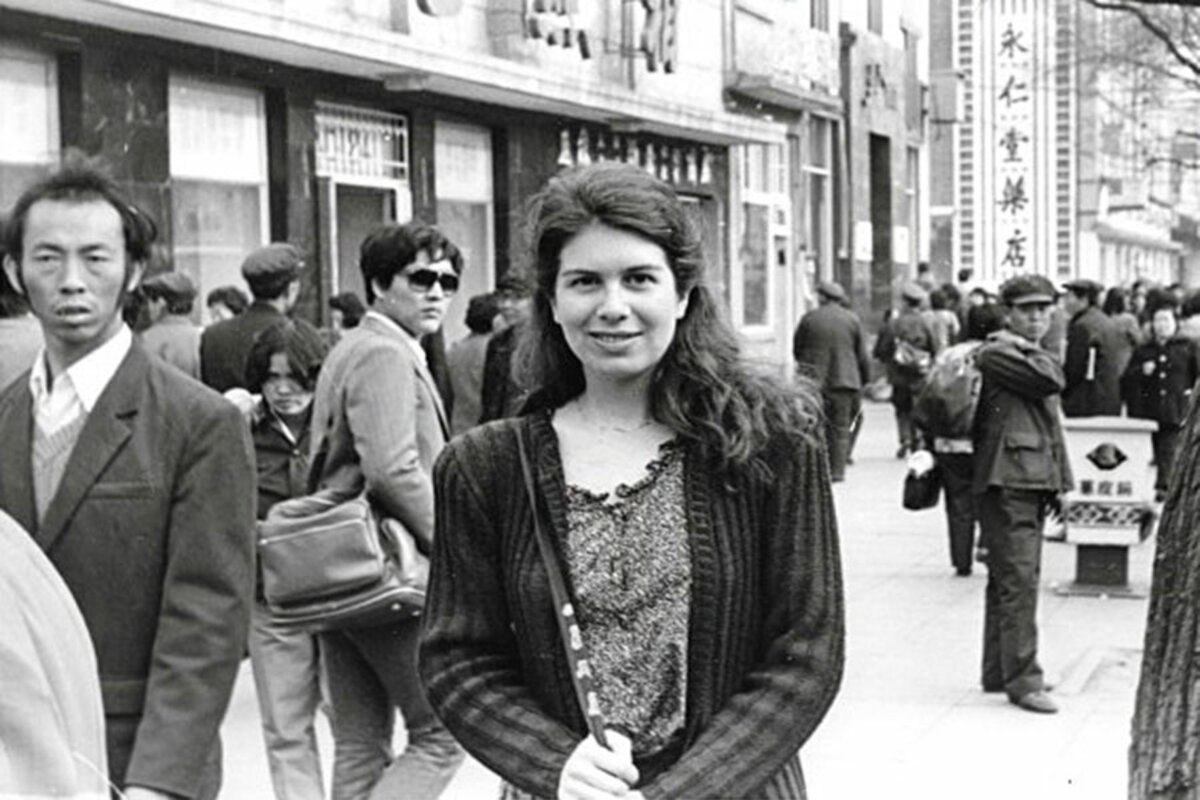

I’ve arrived in China, but I feel worlds away from the country I first encountered decades earlier. A gray, frozen landscape greeted me when I flew into Beijing one wintry November day in 1983. The airport road was empty but for a few people bundled in ragged clothes pedaling bicycles, and a panting horse pulling a wobbly cart. I was fresh out of college and taking up residence as a novice reporter.

It had been only seven years since Mao Zedong’s death in 1976 and the end of his fanatical Cultural Revolution. The country was isolated and poor, its

1 billion people exhausted and traumatized by economic stagnation, famine, and political purges. China’s 800 million peasants toiled on “people’s communes.” Urban workers had an “iron rice bowl” of assigned jobs and food rations.

For most of the next decade, I lived in Beijing and Hong Kong, taking a front-row seat as pragmatic leader Deng Xiaoping jettisoned communism for capitalism, and China sprang to life. In the spring of 1989, I watched the buildup of a pro-democracy movement. Hundreds of thousands of Chinese rallied in Beijing’s Tiananmen Square, only to face a brutal military crackdown on June 4.

Many of my contacts disappeared into hiding, jail, or exile. Few Chinese dared speak with me. Taking my infant son for a stroll in Beijing’s Ritan (“Temple of the Sun”) Park was one way to have innocuous contacts. Even then, plainclothes police sometimes followed us. Later, I managed to evade authorities and travel, capturing the life stories of several Chinese for a book I co-wrote. By the time I left in 1992, China was a second home. I spoke and often dreamed in Chinese. In many respects, I knew China better than I did my own country.

Now back to visit my son in Shanghai, I am eager to rediscover China after 25 years – and see whether I can reconnect.

What most surprises me about Shanghai and the country are the extremes, the sheer magnitude of it all. China, I know, is the world’s biggest trading nation. Soaring growth has lifted more than 700 million Chinese from poverty since 1990, creating a robust middle class and hundreds of billionaires. After a mass migration from villages, more than half of Chinese now live in cities. Still, I was skeptical about China’s ability to modernize against such huge odds. In Shanghai, those doubts vanish.

“China has with remarkable speed restored itself to ‘wealth and power,’ fuqiang, the watchwords of Chinese nationalists from the late 19th century on,” says Chas W. Freeman Jr., a veteran United States diplomat now in academia.

Mr. Freeman recalls arriving at Shanghai’s airport in 1972 as an interpreter on President Richard Nixon’s historic trip, and hearing birds sing. “There were no aircraft,” he says. China “was a cultural desert in the middle of [Mao’s] Cultural Revolution.”

Today, Shanghai is a thriving, cosmopolitan metropolis, every bit as chic as Paris or New York – and with more people than any other city proper in the world.

From the window of my son’s apartment, skyscrapers stretch across the horizon. Far below, people flow down tree-lined streets by bicycle, scooter, automobile, and DiDi car (the Chinese ride service now rivaling Uber). Shanghai has 1,000 bus lines and the world’s largest subway system, its riders orderly and aloof.

The city boasts the world’s busiest container port and fourth-

largest stock exchange. “China is not trying to make revolution anymore; it is trying to make money, which is much more wholesome,” says Freeman, a senior fellow at Brown University’s Watson Institute for International and Public Affairs.

I stroll down Shanghai’s upscale Nanjing Road, past displays of Swiss watches and designer fashions. At the 1920 Art Deco French Club, now a hotel in the former French Concession, I discover an extravagant Chinese wedding complete with rose petals strewn on a spiral staircase. The bride poses for photos beneath nude sculptures, which are again on display after being boarded up during the Cultural Revolution.

On Fumin Road, school lets out and uniformed children crowd sidewalks and shops, buying snacks such as boiled tea eggs and warm soy milk. Shanghai’s upwardly mobile residents pay $30,000 a year to send their children to private high schools and pave their way to college overseas. Since China’s opening in the late 1970s, millions have left to study abroad, including some 300,000 now at universities in the US.

Chinese are traveling more than ever. On Shanghai’s colonial-era waterfront, the Bund, crowds of Chinese tourists listen to guides describe a “century of humiliation” under foreign powers. Indeed, Chinese tourists far outnumber foreigners at every historical site I visit, from Mt. Huang in the south to Buddhist caves on the edge of the Gobi desert.

But Shanghai, I know, is only one side of China’s story. From there I head west, to the hinterland.

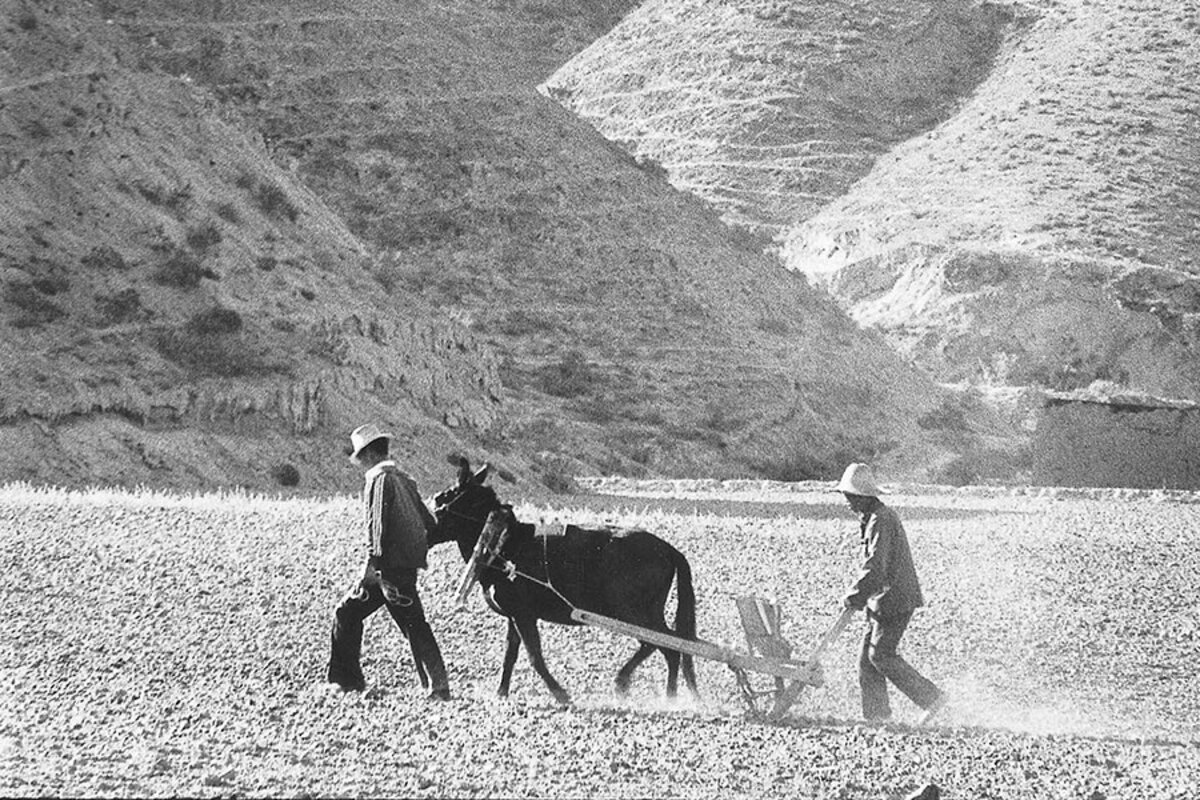

Riding by train through rugged Gansu Province along what was once China’s ancient Silk Road, I scan the landscape of wind-blown loess, expecting to see farmers tending terraced fields as years before. Instead, I see a strange moonscape, a parched expanse. The few clusters of mud-brick homes appear dilapidated and sparsely inhabited, with only some small groups of people harvesting cotton.

The train’s interior seems empty, too, compared with those of the “hard seat” cars I rode in years before. Gone are the crowds of people, jostling and chatting together on wooden seats as they cracked sunflower seeds and sipped jasmine tea from enamel cups.

Occasionally, the train passes a “ghost city,” a jarring block of unoccupied high-rise apartments, evidence of futile government efforts to lure more Chinese to the remote region. A vast wind farm appears, its thousands of alien-looking turbines motionless because of a lack of both demand and transmission lines.

Rural Gansu is the land of China’s have-nots. Its stark contrast with Shanghai underscores the country’s new inequality. In the 1980s, China was one of the most egalitarian societies in the world. Now, it is one of the most unequal. As coastal cities flourished, the rural interior lagged. Shanghai has roughly the same population as Gansu, but is five times as wealthy.

“They have not gone nearly far enough to bridge the gap” between urban and rural areas, says Kenneth Lieberthal, an expert in Chinese politics who has conducted on-the-ground research in China since 1976. Health care and education remain “primitive” in much of the countryside, where most Chinese youth still grow up, says Mr. Lieberthal, professor emeritus at the University of Michigan and a former Asia senior director on the National Security Council.

Migrant workers lack access to urban benefits, including public schooling for their children. They leave behind children and elderly parents, who often struggle.

“I used to grow cotton and corn, but the lack of rain, and the low grain prices made it impossible for me to make a living,” says one older farmer in northern Gansu. A year ago, he took a job as a street cleaner in a nearby town, making about $165 a month. “The wage is low, but many people need jobs so we need to spread it out,” he says.

As China’s population rapidly ages, a consequence of the recently relaxed one-child policy, a pressing question is who will care for the rural elderly, most of whom lack a government pension. Urbanization is hollowing out rural areas, causing the abandonment or destruction of more than 900,000 traditional villages.

“All the young people have left,” says Hu Ziyong, born and raised in a riverside village in Sichuan province, which borders Gansu. She tells me her four children couldn’t make a living farming. Illiterate, she lives alone in a moss-covered stone house, raising a few ducks and chickens.

At a nearby shrine, Ms. Hu burns incense to honor her ancestors, represented by two seated stone figures under a curved roof. I realize how traditional farming villages, with their close-knit communities, folk customs, and ancestral halls, contain much of the essence of Chinese culture. As they disappear to make way for a more modern, materialistic society, a part of China is lost with them.

Venturing beyond China proper, I head upland by bus, toward the country’s ethnic frontiers. China’s population is 91 percent ethnic Han Chinese, but vast border regions – about a third of its territory – are inhabited by Tibetan, Uighur, Hui, Mongol, and other ethnic groups.

Tensions have long simmered as ethnic and religious minorities press for autonomy, bringing harsh reprisals from China’s atheistic government. But there are exceptions.

As the bus rolls past cornfields and into the foothills, I am surprised to see dozens of mosques, each with distinctive domes and minarets, towering over the countryside. This territory belongs to the 10-million-strong Hui ethnic group, which has long assimilated with Han Chinese, speaking the same language, intermarrying, and living dispersed throughout China. Unthreatened by the Hui, Beijing is unusually tolerant of their religious activities.

In contrast, the government is tightening controls on Buddhists in Tibet and Muslims in Xinjiang, where authorities have reportedly destroyed mosques, forbidden officials from fasting at Ramadan, and imposed other restrictions on worship in the name of preventing terrorism.

The bus climbs into the mountains, past a white stupa draped with prayer flags, and stops near Labrang Monastery, a major center of Tibetan Buddhism with about 2,000 monks and six colleges. At dawn, Tibetan pilgrims in long-sleeved cloaks circle Labrang, chanting and spinning prayer wheels.

Security cameras inside Labrang monitor the monks’ activities. Monks are required to undergo political indoctrination critical of their exiled spiritual leader, the Dalai Lama, who seeks greater autonomy for Tibet, and are barred from displaying his portrait.

In and around Labrang, I spot only one photograph of the Dalai Lama, high on the wall in the corner of a Tibetan clothing shop. “Whenever there is a crackdown, I cover it,” explains the shopkeeper, using a yellow silken cloth as a quick curtain. She folds her hands and bows toward the image.

Monks at Labrang and other monasteries staged demonstrations against Chinese policies in Tibet in 2008, and since then scores of Tibetans have self-immolated in protest. Several monks from Labrang have been arrested, and some remain in jail, local Tibetans tell me.

“Our religious leader is the Dalai Lama; we want him to choose the incarnations, not the Communist Party,” says one Tibetan resident, a former herdsman, referring to the sacred process of identifying successors to high lamas. “The party controls everything – politics, religion, and culture.”

A large Chinese paramilitary installation stands several blocks from Labrang. Armed police patrol the streets, ramping up during Tibetan festivals, residents say.

China’s heavy-handed religious repression and security presence in Tibet and Xinjiang, along with the resettlement there of millions of Han Chinese, is driven by a greater objective: to secure the country’s strategic and resource-rich periphery at all costs.

The border areas, especially Xinjiang, are critical to China’s ambitious push to expand its economic power, security, and leadership role across Asia and beyond. Under its trillion-dollar “Belt and Road” trade and investment initiative, China will build roads, pipelines, and ports throughout Asia to Europe, a plan involving as many as 65 countries with a total of 4.4 billion people.

“China is moving ahead more rapidly than any of us appreciate,” says David Lampton, a professor of China studies at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore. He is writing a book on China’s construction of high-speed railroads. “We need to wake up and realize China is a competitive force.”

Communist Party chief and President Xi Jinping recently called for building “a great wall of steel” around Xinjiang to guard against Islamic extremism. Echoing this sentiment, a sign at a military installation near the Tibetan region likens China’s Army to the Great Wall. Yet the heightened security measures risk backfiring, perpetuating a cycle of ethnic unrest.

As I prepare to catch a flight to Beijing, it occurs to me that while China’s leaders are nervous about minority unrest, they are far more fearful of dissent among the majority Han Chinese.

Traveling across China, two faces are unavoidable – those of Mr. Xi and People’s Liberation Army soldier Lei Feng, the legendary 1960s communist role model.

On a giant video screen above Shanghai’s train station, Xi appears in camouflage fatigues, reviewing a phalanx of troops. At the westernmost watch tower of China’s Great Wall, he hovers larger-than-life in a poster, dwarfing the wall itself.

Lei, in his furry ear-flap hat, looks down on city streets and transport hubs, reminding citizens to help others and practice the 12 “core socialist values” – the state-

imposed moral code.

The two images are emblematic of Xi’s consolidation of power to a degree not seen in China for decades, and his aggressive push for Communist Party supremacy and ideological conformity. Xi’s name and “thought” were enshrined in the party’s Constitution in October, and all Chinese – including the country’s 228,000 journalists – are being urged to study it. One Chinese shopkeeper I speak with goes so far as to call Xi “China’s second Mao Zedong.”

As impressed as I am with China’s modernization and confident world outlook, I am troubled by the party’s unbridled impulse to control the Chinese people – reflecting what seems to be a deep domestic insecurity.

The party’s mandate depends on its ability to make good on what Xi calls China’s dream – a nationalistic vision of a strong, prosperous China regaining its place at the center of the world. Rejecting the West as a model, Xi sees China setting the example for other nations.

To achieve this, the party must tackle serious problems: rising inequality, corruption, overcapacity in heavy industry, and severe pollution. China’s growing middle class is eager to secure its hard-earned wealth through property rights and the rule of law. Experts believe China could smooth this process by encouraging civil society and organized political participation, fostering paths to compromise.

Instead, China’s leaders are tightening their authoritarian grip. Beijing is reining in nongovernmental organizations, and arresting activists, human rights lawyers, and bloggers, according to Freedom House, an independent watchdog group.

It is also building a high-tech surveillance state. Authorities use cameras, some enhanced with facial recognition software and artificial intelligence, to watch people, unconstrained by privacy protections. Individuals are monitored for “untrustworthy” behavior at work and in public places, as well as online and on their phones. The government reportedly plans to assign each person a “social credit” score that will affect access to jobs, schools, and even airline tickets.

Chinese officials manipulate the internet, blocking websites, posting and deleting social media comments, and scrutinizing texts. Foreign television is censored in China. I saw CNN and BBC broadcasts cut off when commentary turned critical of Xi. The party controls universities, where lectures are videotaped.

“If someone crosses an ideological line, they can be punished,” says Elizabeth Perry, a professor of government at Harvard University in Cambridge, Mass.

In Beijing, I decide to walk to Tiananmen Square to see the flag lowered at dusk. After passing multiple security checkpoints, I join a crowd of hundreds of Chinese. As white-gloved military guards fold the flag with a flourish, onlookers capture it with cellphones. I wonder how many of these mostly young Chinese think about the 1989 Tiananmen democracy protests, or the blood that was spilled where they stand.

The day before I’d met a Chinese man, his hair speckled with gray, who was a university professor in Beijing in 1989. On the night of June 4, he made his way past soldiers and tanks to the square to make sure his students escaped.

“I always feel ashamed now when I go there,” he said in a low voice. “The Army should never open fire on its own people. It should defend them.” Frustrated by the party’s intensifying controls, he said China needs more democracy and freedom, but many Chinese are blinded to this by materialism.

After the color guard marches off, vans full of police, barking through loudspeakers, herd the crowd out of the square. I walk down a side street, past vendors selling steaming corncobs and sticks of candied hawthorn. Several blocks away, I realize I am being followed by plainclothes police. Unfazed, I eat dinner and return to my hostel down a narrow Beijing alley.

My trip is coming to an end, and I feel an inexplicable sadness.

The next morning, I go looking for my old neighborhood in eastern Beijing. Emerging from the metro, I enter a canyon of concrete and glass buildings and struggle to get my bearings. Finally, I find the gate to Ritan Park, where I used to push my son in his stroller and collect child-rearing tips from Chinese grandmothers.

Walking down a stone path lined with willow trees, I approach a familiar red-pillared pavilion on the edge of a small lake. The sounds of a Chinese erhu fiddle and drum meet my ears, and without warning a wave of emotion sweeps over me. Tears roll down my cheeks as I sit on a bench, listening to the amateur opera group perform, exactly as I remembered. The next thing I know, a middle-aged Chinese man sits down next to me.

“Why are you crying?” he asks, patting my shoulder.

“The music,” I manage to say. He begins describing the opera – Yu opera from Henan province – in halting English. Switching to Chinese, I explain that I know the park. I lived nearby many years ago. “I’m sorry,” I say, “I can’t stop crying.”

“Don’t worry,” he says, trying to cheer me up. “You look like a movie star ... like Nicole Kidman.”

I have to laugh. With that, we begin a long, far-reaching conversation. As fate would have it, he is a journalist about my age, and began living in the neighborhood about the same time I did. He speaks freely of Chinese perspectives on America and of Xi, describing how people evade internet restrictions, and the prospects for China democratizing. Two hours quickly pass. I wonder whether we could stay in touch.

“As a journalist, if I have contact with foreigners, it will bring difficulties for me that I don’t need,” he says. “Ask me whatever you like here, now.”

We talk more, while listening to the opera. I know once the conversation ends, I will likely never see him again. As I prepare to go, I struggle again to hold back tears.

“Don’t cry,” he says. “Don’t cry for Beijing.”

I walk away without turning around, finding another place to sit and gather my thoughts. Several minutes later, I look up. He is standing in the distance watching me. Once our eyes meet, he smiles and waves. I wave back. He is gone.

The meeting brings an epiphany of sorts. Traveling across the country, I was subconsciously searching for the China I knew so well, a place that was slower paced and earthy, less jaded and detached. The park offered a glimpse of it, although in many ways that China no longer exists. Still, the heartfelt encounter makes it all right. Kindness is timeless. The willingness to cross whatever barriers exist to form a human connection – nothing can take that away.