- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- Next, Trump on Trump? What to expect as Mueller probe deepens

- Why France tilts toward a more entrepreneurial future

- Racial justice: At Georgetown, Jesuits and slave descendants face history

- Without prison as lever, Oklahoma seeks paths to drug treatment

- In Colorado, a ‘keystone’ species that’s also a pest

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Monitor Daily Intro for January 25, 2018

Yvonne Zipp

Yvonne Zipp

In Turkey, one man’s trash has become an entire city’s treasure.

Sanitation workers in Ankara have opened a free lending library with books they salvaged. The workers created it for friends and families. The collection grew so large they worked with the local government to share it with everyone.

The more than 6,000 books are housed in an abandoned factory building, CNN reports. The library is filled with students and the children of city employees. Cyclists come to drink tea and play chess. And word has traveled: “Village schoolteachers from all over Turkey are requesting books,” the mayor said.

The hunger for books is something Monitor readers and writers understand. For years, Home Forum essayist Kate Chambers has been distributing books in Zimbabwe, whose people, she writes, long for reading material.

"This is an informal project, born of the deep gratitude I have for the part books have played in my life," she says in an email, saying that at one point, there were so few books available she would buy old car magazines for her son to read. She wrote about it in this story and in this one.

"Readers started emailing my editor, asking how they could help. I answered each email with a request for just small parcels .... Then the parcels started coming," she writes, saying about 30 Monitor readers have mailed books, as have as her mom, friends, and others. "I've lost count of the number of books I have given out ... over the last eight years it must be more than 8,000...."

Now, here are the five stories we've chosen for you today, looking at a country's shift in thought, paths to progress in fighting addiction, and the thorny question of how to properly make amends for sins long past.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Next, Trump on Trump? What to expect as Mueller probe deepens

The president says he would "love" to sit down with the special counsel, possibly sometime in the next few weeks. But given Donald Trump’s well-known penchant for hyperbole, his lawyers may be concerned about the potential for misstatements.

In the coming weeks, investigators working with special counsel Robert Mueller are hoping to formally question President Trump as part of their probe into whether Mr. Trump and others conspired with Russia to meddle in the 2016 presidential election, and whether Trump engaged in obstruction of justice. Trump has repeatedly denied the charges. And if the president is worried, he isn’t showing it. “I would love to do that,” Trump told reporters Wednesday of a potential interview. (He added: “subject to my lawyers and all of that.”) Much may depend on Mr. Mueller’s approach – whether he embraces a hyper-technical view in judging Trump’s statements, or allows the president to clear up any suspected misstatements. But there is little doubt about one fact: As the investigation moves into a more mature phase, one of the greatest threats to Donald Trump’s legacy as president could be Donald Trump. “He could easily be his own worst enemy,” says David Sklansky, a professor at Stanford Law School. “I think his lawyers are very likely to be worried about making sure that he doesn’t make more trouble for himself by lying when he is talking to Mueller’s team.”

Next, Trump on Trump? What to expect as Mueller probe deepens

Many in Washington see President Trump as impulsive, sometimes profoundly inarticulate, and prone to bursts of hyperbole. And those are his supporters.

His opponents aren’t nearly as generous. They view the leader of the free world as a congenital liar.

In the next several weeks, investigators and prosecutors working with Special Counsel Robert Mueller are hoping to sit down and formally question Mr. Trump as part of their ongoing probe into whether Trump and others conspired with Russia to meddle in the 2016 presidential election and whether Trump engaged in obstruction of justice when he fired FBI Director James Comey.

Trump has repeatedly denied charges of collusion and obstruction.

It is unclear what evidence has already been compiled proving or disproving the allegations. But there is little doubt about one fact: As the special counsel’s investigation moves into a more mature phase, one of the greatest threats to Donald Trump’s legacy as president could be Donald Trump.

“He could easily be his own worst enemy,” says David Sklansky, a professor and co-director of the Stanford Criminal Justice Center at Stanford Law School. “I think his lawyers are very likely to be worried about making sure that he doesn’t make more trouble for himself by lying when he is talking to Mueller’s team.”

If his testimony becomes a version of his morning tweets or of ‘let Trump be Trump,’ the president may find himself charged with lying to federal investigators, analysts say.

Lying to federal agents or prosecutors is a felony even if the comments are not made under oath.

“Trump is used to being able to say whatever he wants, and then if he later decides to say something different, he just says something different,” Professor Sklansky says. “That doesn’t work when you are faced with federal criminal investigators of the caliber of Mueller and his team.”

If the president is worried, he isn’t showing it.

“I would love to do that, and I’d like to do it as soon as possible,” Trump recently told reporters at the White House of a potential interview. He suggested it might take place within the next two to three weeks. He added as an aside: “subject to my lawyers and all of that.”

Allegations of bias

Speculation about a possible Trump interview comes as partisan tensions continue to escalate in Washington over Republican allegations of bias by top officials at the FBI and charges of US intelligence abuses against the Trump campaign in 2016.

The bias allegations spring from text messages between two FBI officials working on the Trump-Russia investigation that suggest they shared strong anti-Trump political views. Both officials are no longer working on the Trump-Russia investigation.

The controversy gained an added push with revelations that five months’ worth of text messages between the two – covering a critical period in the investigation from Dec. 2016 to May 2017 – had gone missing. Bureau officials said the deletions were a result of a software foul-up, a glitch that also affected thousands of other FBI cellphones. On Thursday, officials announced they had recovered some of the missing messages.

Adding fuel to this fire, Republican members of the House Intelligence Committee have produced a four-page classified memo detailing problems identified with surveillance operations at the start of the Trump-Russia investigation. The memo has been made available for viewing by all members of Congress, and there is debate about whether it should be made public.

Democrats have denounced these efforts as attempts to undercut the credibility of the FBI and help protect Trump in the midst of the ongoing investigation. Democrats have drafted their own classified memo in an effort to expose what they say are misleading aspects of the Republican memo.

Meanwhile, negotiations are continuing to set the terms of a possible Trump interview. Lawyers for the president would likely seek to limit the scope of the questions and ensure that the president’s personal lawyers will be in the room as Trump is questioned.

Such conditions can be arranged as part of a voluntary interview, according to legal analysts. But if Trump were to refuse to submit to an interview, Mueller could issue a subpoena to force Trump to appear and answer questions before a federal grand jury. In that case, his lawyers would not be at his side during the questioning. Trump would face his questioners alone, with his lawyers waiting outside in the hallway.

Trained interrogators

Trained interrogators working for Mueller can be expected to grill the president about any inconsistencies and alleged falsehoods. Analysts expect Trump will face close questioning about his alleged statement to then-FBI Director James Comey that he “hoped” the director would drop his investigation of his former national security adviser, Michael Flynn. He will be asked about the circumstances surrounding Mr. Flynn’s meeting with the Russian ambassador and Flynn’s eventual firing. And he will be asked about the circumstances surrounding his decision to fire Mr. Comey.

How will Trump do? Much may depend on Mueller’s approach to the interview. Will he embrace a hyper-technical view in judging Trump’s statements, or will he offer the president the opportunity to clear up any suspected misstatements?

At least so far, Trump-Russia investigators have been unforgiving when encountering discrepancies and potential false statements.

Flynn pleaded guilty to charges that he lied about whether he discussed US sanctions with Russia’s ambassador in December 2016, a few weeks before he was set to occupy his new office in the White House.

Former Trump campaign aide George Papadopoulos has also pleaded guilty to lying to federal agents about his efforts in mid-2016 to explore contacts with various Russians who allegedly had “dirt” on Hillary Clinton.

Both men have since agreed to cooperate with prosecutors in the ongoing investigation. That suggests they would be available to testify about their recollection of events and conversations should agents detect discrepancies in Trump’s statements.

The Clinton precedent

Grilling a president of the United States about controversial matters is not unprecedented. The country has been down this road before.

President Bill Clinton was impeached (though not convicted) and lost his law license after lying under oath to the special counsel investigating an array of allegations against the Clintons, including whether the president had a sexual relationship with a White House intern.

Although the terms of any Trump-Mueller interview are still not set, the Clinton case may offer a partial template for the meeting.

The Clinton testimony was given under oath in the White House and was broadcast to the grand jury room across town. A key feature of that encounter is that it was videotaped.

It is not clear that Trump would agree to have a video and audio record of the questions and answers. It is also not clear that Trump’s lawyers would agree to create such a record.

But given the president’s apparent distrust of the motives of certain FBI agents and supervisors, a taped interview would help head off disputes about what was said and how it was said, analysts say.

“I think it would make a lot of sense to record the conversation, and I imagine that Mueller’s team would want to do that,” Sklansky says.

And the president may well agree. “Trump himself has often said, ‘I hope there are tapes,’” he adds. “So if he means that, I would assume he would want tapes of this as well.”

Share this article

Link copied.

Why France tilts toward a more entrepreneurial future

The French president campaigned on reforming the French economy, a task that the public has long resisted. But this time, the country seems to be on board.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Speaking at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, Wednesday, French President Emmanuel Macron heralded the entrepreneurial reforms he has overseen in his country. “In France, it was forbidden to fail and forbidden to succeed. Now it should be more easy to fail, to take risk.” Such efforts are not new in France – Mr. Macron’s predecessor, François Hollande, launched the Station F business incubator in Paris that has become the showpiece of French entrepreneurship – but it is under Macron that they seem to finally be taking root. Optimism that France is a good place for business has increased significantly since Macron won, nearly doubling among executives of international firms in France. And Station F, a cavernous converted train depot full of youngsters huddled around laptops with space for 1,000 start-ups, is bustling. “I think [Macron] changed completely the image of France,” says Xavier Niel, the tech billionaire who started Station F. “He has given France a pro-start-up, pro-entrepreneur image beyond our borders that we did not really have.”

Why France tilts toward a more entrepreneurial future

The cavernous converted train depot of Station F, now the world’s largest start-up campus, was under construction well before Emmanuel Macron clinched the French presidency in promise of a bright, entrepreneurial future for the Fifth Republic.

But the vibe here – the youngsters huddled around laptops and taking breaks at video game portals and foosball tables – meshes perfectly with Macron’s brand as a start-up president. In fact, to walk into this space very much feels like stepping back into his campaign headquarters, albeit on a different scale: Station F is the length of the Eiffel Tower, with space for 1,000 start-ups.

Serendipitously for both the president and Station F, the latter opened just weeks after the former’s stunning victory last spring. And together they’ve helped reinforce a new image for France, from a place covered in red tape and restricted by workers resistant to any change, to one called “scrappy” and full of “hustle,” as one entrepreneur here put it.

Perhaps more fortuitously, both have been buoyed by the goings-on in the rest of the world. With Brexit, for example, Macron has stood – as he did yesterday afternoon at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland – as the champion for a stronger Europe with France at its heart; Brexit has also beckoned London-based entrepreneurs to the relative safety of France, in what is now a reverse migration across the channel.

“I think [Macron] changed completely the image of France…. He has given France a pro-start-up, pro-entrepreneur image beyond our borders that we did not really have,” says Xavier Niel, the tech billionaire who started Station F with a 250 million euro ($312 million) investment, in an interview with foreign journalists at the incubator Wednesday. “At the same time that perhaps England doesn’t seem very stable with Theresa May, perhaps that Germany doesn’t seem as fun with a leader whose [mandate] is getting old, maybe because the United States with Donald Trump doesn’t seem very welcome to foreigners … we, in the midst of this, are not doing badly.”

Choosing France

In reality, the start-up culture in France was thriving before Macron. It was the unpopular previous president, François Hollande, who broke ground on this space just off the Seine in October 2014, well before Macron was even considered a presidential contender.

But perceptions matter, says Niel. And Macron has pushed fast-forward – particularly this week as world leaders gather in Davos – on trying to foster entrepreneurship, lure in investment, and prove that France is not the bureaucratic nightmare that managers picture it to be. So far the French seem to be going along with their president's new tune.

Macron has already pushed through labor reform, despite union attempts to thwart it, making some hiring and firing easier, and offered tax cuts to spur more investment and boost employment. This is happening as growth has finally returned to the eurozone, after a decade of recession and then stagnation.

On Monday, ahead of the opening of Davos, Macron invited 140 business executives to the Sun King’s palace at Versailles to pitch the country as the new place to be. It was, fittingly, called “Choose France.” In addition, executives from Facebook and Google were in attendance, and both announced new investment in artificial intelligence in France.

Optimism that France is a good place for business has increased significantly since Macron won, nearly doubling among executives of international firms in France, according to an Ipsos poll in November, from the year before.

Not all French are buying it. If Macron is a darling of the global elite, the French public is far more guarded. Macron’s popularity stands at 50 percent, while 49 percent say they are dissatisfied, according to an Ifop poll this month. He’s been dubbed the “president of the rich” by the left, and while Station F is buzzing, outside many workers are locked out of the market or stagnating in jobs, afraid to leave the security of ironclad benefits.

Philippe Martinez, boss of the hard-line CGT union, repeated as much in a recent interview with foreign journalists. He derides the undoing of social protections in favor of profitability. “The Anglo-Saxon model, countries like the UK and US, are Macron's model,” he says.

‘A hustle mentality’

But despite that dissent, the French streets are relatively quiet. And that goes back to impeccable timing. Catherine de Wenden, a political scientist at SciencesPo in Paris, says that the ending of the economic crisis has not enamored the French of their president, but it has given him space to try and effect change. “As the economic situation is better … people are ready to accept some reforms,” she says.

Macron campaigned on a mentality shift that he reiterated in a speech in Davos yesterday afternoon, delivered in English and then French, backing a “nation of entrepreneurs,” he said. “In France, it was forbidden to fail and forbidden to succeed. Now it should be more easy to fail, to take risk.”

There is no better testing ground right now than Station F. Modeled after an American campus, the group is now building a housing unit with space for 600 entrepreneurs to live. They have brought bureaucratic services inside to help with taxes and visas. Twenty-five percent of the start-ups are not created by the French. Niel speaks of a mixing of cultures and social background – similar to Macron’s message of openness – to spark ideas and creativity. A new program called “Fighters” is designed only to support entrepreneurs from disadvantaged situations.

Roxanne Varza, who is an American and the director of Station F, says that there is a lot of international appeal. One of the programs they run drew applicants from 50 different countries, from as far away as Jamaica and Nepal. “But the countries with the most [applicants] were the US, UK, China, and India in that order,” she says.

Christine Foote, who grew up in Utah, spent that last eight years in San Francisco. There she joined the software start-up Lead.ers, whose team was majority French but started in California. The team relocated operations to Paris and are now housed in Station F. “San Francisco feels more established. There are more rules, and I think people in Paris are starting to have more of a hustle mentality. Or they are a little bit scrappier, in a positive way,” Ms. Foote says.

“I had the same stereotypical idea that French people have so much vacation and they don’t love to work or have the same work ethic that Americans have,” she says working with her team after hours. “But I found the opposite to be true.”

Ms. Varza says there is a “Macron effect” that is on display at Station F, and in France. “It is a catalyst effect,” she says. “He did not create what is happening. But he came at a very good time.”

Racial justice: At Georgetown, Jesuits and slave descendants face history

The 1838 sale of 272 enslaved people wasn’t the first or the last the Maryland Jesuits made, but it was the largest. If Georgetown and the Jesuits commit to reparatory justice, observers say, they could embolden others to push their universities to follow suit.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 10 Min. )

It’s no secret that Georgetown University and other American colleges depended on slave labor. But racial oppression and the hope for reconciliation take on new meaning when the descendants of both sides of that history come together to consider what to do now. Today’s conversation in tiny Maringouin, La., has been 179 years in the making. About 80 descendants turn out to talk with visiting Jesuits – who represent the Roman Catholic order that ran Georgetown and sold 272 enslaved people to Louisiana owners in 1838. Among them is Jessica Tilson, the great-great-great-great-granddaughter of Cornelius “Neily” Hawkins, about 13 at the time of the sale. One by one, descendants share ideas about how the Jesuits could help with everything from memorials to scholarships to racial justice projects. Some push for moving from talk to more concrete forms of reparation. For Johnnie Pace, husband of a descendant, the import of the moment can’t be overstated: “I am 74 years old,” he says, pounding his fist to hold back tears. “I never thought that I would live to see the descendants of slaves, the descendants of slaveholders, come together in love.”

Racial justice: At Georgetown, Jesuits and slave descendants face history

Jessica Tilson walks on soggy grass between the gravestones, rattling off names from her family tree, a thin black sweater the only barrier between her and the cold that came with a once-in-a-decade snowfall. She keeps the interwoven branches of her family in her head, along with a map of who’s buried in the unmarked parts of the Catholic cemetery in tiny Maringouin, La., – a rural town surrounded by sugar cane fields, bayous, and giant oaks.

Among those she honors by cleaning their graves is Cornelius “Neily” Hawkins, her great, great, great, great grandfather. Neily was about 13 when slave traders forced him onto a ship in Maryland and transported him to the West Oak plantation, where the sugar industry thrived through labor extracted by brutality.

The Jesuits who ran Georgetown University and plantations in Maryland had sold him, along with 271 others – including his brothers and sisters, his parents, and his grandfather, Isaac Hawkins, born just a few years before America gained its independence.

That 1838 sale wasn’t the first or the last the Maryland Jesuits made, but it was the largest, and some Jesuits opposed it at the time, despite their mounting debts. The names of the men, women, and children transported to various parts of Louisiana were recorded, and they have since become known as the GU272.

Now, Jesuit leaders are coming here for the first time – and Ms. Tilson hopes they will visit such sacred spots and hear the stories she’s unburied.

For many who hail from Maringouin (“mosquito” in French) and other parts of Louisiana, this December meeting will be their first opportunity to talk with representatives of the religious order that enslaved and sold their ancestors.

It’s another step in a reckoning that’s been unfurling in slow motion. For nearly two years, the connections between the 272 and several thousand living descendants have been emerging, impelling new relationships and debates about how best to address the modern-day legacies of slavery.

Unlike other historic American universities that held slaves and have since shed their religious identities, Georgetown “had to deal with the moral component of it, the way that it actually challenged Georgetown’s identity as a Catholic institution … committed to the Jesuit sense of social justice,” says Craig Steven Wilder, a professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and author of “Ebony and Ivy,” a book on universities and slavery.

“The human dimensions of the story” are unavoidable, Professor Wilder says, because “descendants of the sale of 1838 have put an extraordinary human face on these historical facts.”

Those descendants hold a diverse array of ideas about what should happen next – everything from modest requests to memorialize forgotten sites in Louisiana to a hope for a $1 billion foundation to address racial disparities, assist descendants with education, and support racial reconciliation.

“Although slavery in the United Sates ended many years ago, there has been a continuum of racial oppression…, and we have to heal those racial tensions in order for this country to move forward,” says Karran Harper Royal, the New Orleans-based executive director of the GU272 Descendants Association, one of several organized groups.

***

It’s a Saturday afternoon and descendants are arriving at the modest rectangular parish hall next to Maringouin's Immaculate Heart of Mary church. Many of the 272 maintained a Catholic identity despite years in which they were deprived access to priests, in violation of the terms of the 1838 sale.

Those ancestors “believed in God despite everything ungodly around them. I’m still humbled by that kind of faith,” says descendant Lee Baker, before the meeting that he helped organize gets under way. He needed resilience – which he now sees runs in the family – when he helped integrate Catholic institutions in the 1960s. Now he teaches at a Catholic high school near New Orleans.

One tall man saunters in wearing crisp denim overalls, another a three-piece-suit, until about 80 people are assembled in metal folding chairs. A table covered with a white cloth is set up in the front, where the Jesuits will sit.

For the older generations, especially, slavery isn’t something people talk about much here. But today’s conversation has been 179 years in the making.

Georgetown’s dependence on enslaved African and American families wasn’t a secret. But a few years ago, student journalists, activists, and a working group appointed by the university started questioning why people such as the Rev. Thomas Mulledy, S.J., Georgetown’s president in the early 1800s, were still honored on campus buildings despite their role organizing the 1838 sale.

Alumnus Richard Cellini became curious about what happened to the 272. When he heard that they had all died of fever in Louisiana, his incredulity led him to search in Google and quickly connect with a descendant. Later he started the nonprofit Georgetown Memory Project to assist with genealogical research.

The family trees have blossomed as people analyze DNA and dig into archives. So far, nearly 6,000 direct descendants (living and deceased) have been identified out of what could eventually rise to 15,000, Mr. Cellini estimates.

Last spring, Tilson and several other descendants attended a ceremony at Georgetown to replace Reverand Mulledy’s name with Isaac Hawkins on a now-residential building. President John DeGioia and representative Jesuits offered apologies during a “Liturgy of Remembrance, Contrition, and Hope.”

These were some of the steps recommended by a working group the university had appointed before they knew any descendants.

Now, several descendants are attending Georgetown, which has offered “legacy” admissions preferences.

Many descendants say they are grateful for what’s happened so far, but that it’s time for the process to become less Georgetown-centric and more inclusive of their voices.

It’s still unclear whether these large institutions will be willing to hold themselves accountable in ways that go beyond symbolism, that actually involve shifts in power dynamics or substantial monetary investments.

The next step is “talking about reparation,” says Adam Rothman, a history professor at Georgetown who served on the working group. “What would be an adequate gesture of repair? That’s a lot of what people are debating.”

It has often seemed like the Jesuits wanted “to have their act of contrition, skip right over penance, and go straight to forgiveness,” says Sandra Green Thomas, president of the GU272 Descendants Association, who attended the Georgetown ceremonies, as well as a morning meeting with the Jesuits in New Orleans on this same December day that they’ll be visiting Maringouin.

She wants the outcome of talks to be action that benefits people beyond those who can attend Georgetown, but she also points out the irony that her two children now there will graduate with debt, despite financial aid, while Georgetown students once had tuition subsidized by the enslaved.

“My hashtag is #OurTuitionHasBeenPaid … with the blood, sweat, and tears of our ancestors,” Ms. Thomas says.

So far, institutions have been “reluctant to put dollar amounts on their acknowledgment of a debt,” Wilder, of MIT, says. If Georgetown and the Jesuits commit to reparatory justice, they could embolden others to push their universities to follow suit.

****

The Maringouin meeting has just gotten under way when Tilson scurries in. A single mother of two, she fits her visits to Maringouin in between shifts at two grocery stores in Baton Rouge, where she recently finished her bachelor’s degree in microbiology at the historically black Southern University and A&M College.

After Mr. Baker, the descendant, offers an opening prayer, the Rev. Timothy Kesicki, S.J., president of the Jesuit Conference of Canada and the United States, stands to introduce himself.

Of his Jesuit predecessors who both baptized and claimed ownership of slaves, he asks, “How is it that they received the same sacraments, prayed the same prayers,… and failed to see themselves as equal before God?”

The room is quiet as he continues solemnly, “I am sorry to you, the descendants, but I also say before God ... that as Jesuits, we have greatly sinned in what we have done and in what we have failed to do…. I come [here] to understand what are the next steps in reconciliation, what are the next steps in healing this gaping wound.”

Tilson leans against the wall, in jeans and a Georgetown sweatshirt, recording with her pink cell phone.

The Rev. Robert Hussey, S.J., provincial of the Maryland Province Jesuits offers apologies as well, adding, “Healing ... is about concrete actions.... We want to explore with you what would be the most meaningful way … to be part of things that can create new life and new opportunities for people.”

For the next hour, local residents and those who have traveled from as far as Ohio and California rise to share their thoughts.

Some focus on the joy of discovering new family ties and answers to questions that always puzzled them: Why didn’t their families speak French or cook Creole?

Others offer specific ideas for how the Jesuits can make a difference.

Tilson strides up front and places a mason jar filled with black soil on the table, a dark blue ribbon tied around its neck, explaining that it is from Georgetown.

“What I would like for the Jesuits to do is to take the soil ... and go to West Oak and give our ancestors a proper burial.... The ones who died before the church was built ... we don’t know where they at,” she says, her voice rising in pitch as the emotions rush out. “They could have been thrown in holes over there, they have alligators back there.... So you guys owe our ancestors a proper burial.”

Fathers Hussey and Kesicki look up at her with compassion. They’re taking notes and holding off on responding until the end.

Other speakers bring up broader needs in descendant communities – prenatal care, assistance with college expenses. Among Maringouin’s roughly 1,000 residents (the majority descendants) the per capita income is $15,000.

“I feel like this is going forward and then two steps back. We are out here. We are looking for something to happen,” says Matthew Mims, a local aspiring dentist who recently graduated from college. He’s not the only one for whom patience with ceremonies and conversations is wearing thin.

But this is an opportunity for descendants to ask something not only of the Jesuits, but also of the large extended family seated before them. It’s a chance to challenge the institutionalized racism that slavery and Jim Crow left in their wake.

This is an area where notorious slave traders are still honored in whites-only cemeteries, where families still hold memories of lynchings.

Michelle Harrington, who long ago moved away, says she’s disappointed that in the church, blacks still sit on one side and whites on the other. “Sit on the other side,” she pleads. “Make somebody uncomfortable. We cannot be enslaved any longer.”

***

One of the last speakers to step forward is Johnnie Pace, tall with silver hair, glasses, and a black jacket. He’s married to a descendant of Isaac Hawkins, and shares how warmly he was welcomed at Georgetown during a recent unannounced visit.

“Granted, we can’t change history…. But we can change the future and we can change today. I am 74 years old,” he says, pausing and pounding his fist to hold back tears. “I never thought that I would live to see the descendants of slaves, the descendants of slaveholders, come together in love.”

Kesicki and Hussey stand and respond, briefly but earnestly, to what they’ve heard. They share how they’ve hired archivists to ensure that more church records are made accessible online, how they want to spread awareness of this important story.

They assure the group that they will follow up soon about setting up a process for further dialogue.

While there will be no official ceremony today, they do pay a visit to the cemetery with Tilson and a few others after the meeting. She points out the small, broken headstone of Lucy Ann Scott, her great, great, great, great aunt who was sold in 1838 and was buried near the graves of Tilson’s own sister and son. Maybe they could supply a new headstone for Lucy, she suggests.

Standing on the grave of another relative sold in 1838, she barely takes a breath, sharing as much as she can fit in before twilight. Hussey shakes his head and smiles. “Astounding,” he says.

In the years leading up to 1838, “Y’all supposed to send us back to Liberia, but y’all didn’t,” Tilson says without a hint of bitterness.

In the distance, a train rumbles by. It’s slow, like the building up of trust.

The air grows colder by the minute and Kesicki and Hussey head out before darkness engulfs the rural roads.

“I’m happy because I got an opportunity to show them what happened,” Tilson says. “That child you sent to Maringouin, this is their spot – this is their resting spot.”

*Reporter’s note: By mid-January, Georgetown and the Jesuits were circulating a set of draft principles for collaborating, and asking descendant groups for feedback. Kesicki reflected on the Maringouin meeting in a phone interview: “It was only there, face to face, that I felt personally the pain of those who have come to know who held their ancestors enslaved.”

Road to Reconciliation

Without prison as lever, Oklahoma seeks paths to drug treatment

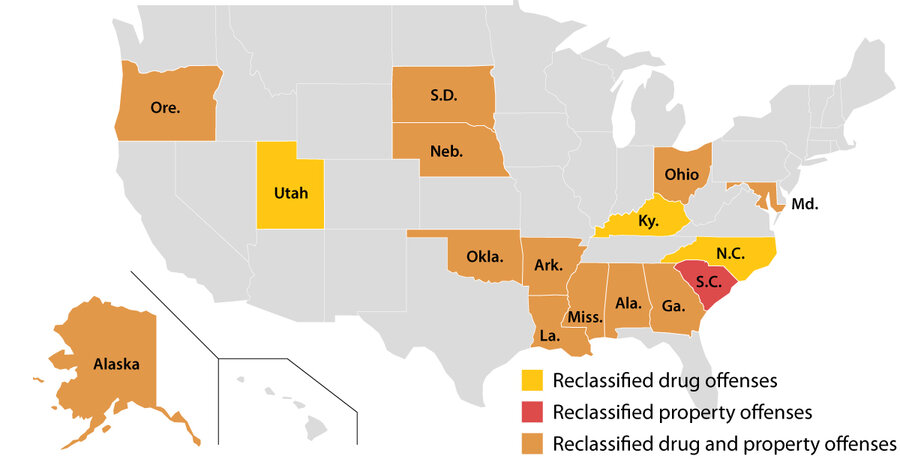

What happens when drug offenses no longer lead to felony charges? Do addicts avoid prison and get treated for substance abuse? Or simply pay a fine and walk away? Oklahoma, a tough-on-crime state that changed possession from a felony to a misdemeanor in 2017, is finding out.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Oklahoma spends more than $500 million a year on its prisons, in part because the state’s rate of incarceration is second only to Louisiana’s. Alarmed by those costs, voters approved a ballot initiative to reclassify drug possession and minor thefts as misdemeanors. The reform, which took effect last July, was passed despite concerns from law enforcement agencies and public prosecutors who questioned how they would control criminals without the threat of prison. Still, it mirrored efforts by other states, including Louisiana, looking for ways to end mass incarceration – even as the Trump administration has rowed in the opposite direction, urging federal prosecutors to seek longer prison sentences. It makes sense for states to reform drug sentencing since punitive laws don’t appear to curb drug abuse, says Adam Gelb, a criminal-justice expert at The Pew Charitable Trusts. “Locking up more drug offenders increases punishment, and if that’s the goal, then it works,” he says. “If it’s about improving public health and safety, the numbers don’t back that up.”

Without prison as lever, Oklahoma seeks paths to drug treatment

What happens to drug-crime policing when you take away the stick? A tough-on-crime state with swelling prison rolls is about to find out.

In 2016, voters here approved a closely fought ballot initiative to reclassify drug possession and minor thefts as misdemeanors. The idea was to steer nonviolent drug offenders who stole for their habit away from prison and into treatment programs. The reform appealed both to voters here alarmed at rising prison costs – Oklahoma’s rate of incarceration is second only to Louisiana’s – and those who saw locking up nonviolent addicts as futile.

The reform passed over the opposition of law-enforcement agencies and public prosecutors, and was rejected in many rural counties. But it mirrored efforts by other states, including Louisiana, looking for ways to end mass incarceration, even as the Trump administration has rowed in the opposite direction, urging federal prosecutors to seek longer prison sentences.

It makes sense for states to reform drug sentencing since punitive laws don’t appear to curb drug abuse, says Adam Gelb, a criminal-justice expert at The Pew Charitable Trusts. “Locking up more drug offenders increases punishment, and if that’s the goal, then it works. If it’s about improving public health and safety, the numbers don’t back that up,” he says.

Across the country, the number of people in state and federal prisons fell in 2016 to about 1.5 million, down from 1.6 million in 2009 and the third straight year of decline, according to the Bureau of Justice Statistics.

Debate over reform's efficacy

Oklahoma’s reclassification took effect last July and the debate over its efficacy remains potent: Republican state lawmakers tried unsuccessfully to dilute the changes and may try again in this year’s session. For their part, reformers are also trying to advance criminal justice bills.

In Oklahoma County, the largest jurisdiction, the changes are apparent. Last year, prosecutors filed the lowest number of felony cases since 2011, while the number of misdemeanors rose by 37 percent from the previous year. This reversal was seen across the state, with a 26 percent drop in felonies on court dockets.

So what happens when drug offenses no longer lead to felony charges? Do addicts avoid prison and get treated for substance abuse? Or simply pay a fine and walk away, only to reoffend again?

Capt. Adam Flowers, a detective in the Sheriff’s Office of Canadian County, which straddles Oklahoma City’s suburbs, says it’s the latter. The ballot measure, while well-intentioned, is tying the hands of officers who deal with addicts and petty criminals on a daily basis. “If it’s just a misdemeanor and you’re not going to prison, it takes the teeth out of what we’re going to do,” he says.

Tough sentences for drug-related offenses, mostly methamphetamine, have helped to crowd Oklahoman prisons, including those for women, whose rate of incarceration is the highest in the United States. Nearly one-third of all state prison inmates were convicted of drug offenses, according to a 2017 report by a state task force on justice reform that proposed major changes in sentencing, probation, and other aspects.

For meth addicts who commit nonviolent crimes, treatment is clearly a better and cheaper option, says Mark Woodward, a public-information officer at the Oklahoma Board of Narcotics. It costs about $19,000 a year to keep an offender in a state prison in Oklahoma, compared with $5,000 for a community-based rehabilitation program.

But like Captain Flowers, Mr. Woodward is concerned that the lighter touch for low-level drug crimes will reduce participation in substance-abuse programs. “We’re not locking them up or giving them an incentive to go to treatment, or to stay in treatment,” he says.

Treatment still an option

Reformers say that courts are still directing addicts into treatment and that prosecutors have leverage to cut deals, even with a reduction in felony charges. “The stick is not being taken away. It’s perhaps bit smaller, but the research is clear that it is still of sufficient size,” says Mr. Gelb, who directs Pew’s Public Safety Performance Project.

Drug distribution and trafficking remain felonies in Oklahoma; the same applies to property crimes where the value exceeds $1,000. And felons convicted of dealing drugs face stiff penalties: The average sentence is more than eight years.

Moreover, misdemeanors for drug and property offenses can result in jail time, and that creates an opportunity to seek treatment, says Ryan Gentzler, an analyst at the Oklahoma Policy Institute, a left-leaning think tank in Tulsa.

“People who struggle with addiction are not long-term planners. Any arrest, any time behind bars, is going to weigh the same in their judgment,” he says. “Whether they decide to use drugs has very little to do with the amount of time they’re threatened with.”

Terry knows all about addiction – and treatment. Age 37, he has been using meth since he was a teenager. He blames it for his chaotic life and the 11 years he spent in prison for burglary. “It’s made my life a complete and living hell. There’s nothing good about it,” he says.

Terry is a scrawny six-footer with a scratchy brown beard and prison tattoos on his forearms. Last February, he was arrested in Oklahoma City on suspicion of selling meth and charged with a felony. In November, he received a 15-year suspended sentence under a plea agreement that sent him into rehab.

His first stop was The Recovery Center, a detox facility in Oklahoma City. It was his fourth attempt to get clean. The last time, he says, he completed 71 days of treatment, then within a week relapsed. “I went looking for it without even knowing that I was looking for it,” he says.

Earlier this month, Terry was transferred to a 90-day treatment center in McAlester. “I’m hoping to learn something. Treatment teaches you why you get high, the underlying reasons for doing what you do,” he says.

It’s a chance for Terry to break his addiction – and a condition of his sentence. Still, the idea of being sent to prison doesn’t faze him, since he’s done time before and says meth is easy to score inside. “I am my problem and methamphetamine is my solution,” he says.

Money saved, but skeptics question it

Voters in Oklahoma also approved an accompanying ballot measure that mandates that any money saved by imprisoning fewer people be spent on substance abuse and mental health. This funding mandate echoes a similar proposition passed in California in 2014, which last year redirected $103 million in grants from cost savings from lower imprisonment rates.

Oklahoma has cut the budget of the Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse in three of the last four years. This has led to lower reimbursement rates for private drug-treatment centers and less incentive for these providers to expand services, says Jeff Dismukes, a department spokesman, who says the waitlist for publicly-funded substance abuse programs is currently about 500 people.

“You need to make sure that the treatment [for addiction] is available,” he says. “It’s about getting people to the right services. When you put people into the right services they get well.” Critics of Oklahoma’s reforms point out that California is reinvesting less money in rehabilitation than was promised by backers of the proposition. Oklahoma is to start calculating its savings starting in July.

Public prosecutors are skeptical about the promised savings. David Prater, district attorney for Oklahoma County, told The Oklahoman newspaper that he didn’t expect any savings because public safety agencies, including prisons, were so cash-strapped after years of cutbacks.

Last week, the Department of Corrections requested a budget increase of more than $1 billion, including $813 million to build two new prisons, one for women and one for men. Oklahoma already spends more than $500 million a year on its prisons.

Prosecutors have a financial incentive to push a punitive approach. For every felon on probation or parole, district attorneys receive a $40 a month supervision fee, says Susan Sharp, a sociologist at the University of Oklahoma in Norman. Similarly, sheriff’s offices prefer to move offenders from county jails, which come out of their budget, and into state prisons.

Out in Oklahoma’s rural panhandle, faith-based programs have shown success in turning around former drug users, says George Leach III, assistant district attorney for Texas County and three adjacent counties. The vast majority are users of meth, the illegal drug of choice in the US heartland and the leading cause of drug-related deaths in Oklahoma.

“Usually treatment doesn’t work the first time. By the time we do it twice, 50-60 percent of people we don’t see again,” he says.

Most meth addicts were sent to treatment while on probation for felony convictions, for which the bar is now set much higher. Mr. Leach worries that fewer will now go.

“The issue is not that they can’t get treatment. It’s that they don’t want it,” he says. To stay on meth “is easy. Going through 12 months of treatment is something else.”

Clarification: This article has been updated to reflect the Department of Corrections' total budget increase request.

Pew Charitable Trusts

In Colorado, a ‘keystone’ species that’s also a pest

Is it possible to have too much of a cute thing? The debate over Colorado's booming prairie dog population is testing county officials' ingenuity as they work to placate both farmers and animal welfare advocates.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Prairie dogs create a conundrum across the Rocky Mountain West. Their intricate networks of burrows can disrupt agriculture and irrigation and injure horses and cows, but ecologists note that the prairie dogs are also a critical species – a “keystone” species upon which many others depend – that has lost almost all their historical habitat. In Longmont, Colo., those tensions were on full display last week at a stakeholder meeting that Boulder County held to update residents about prairie dog management and some potential changes to policy. One rancher, so frustrated by the destruction that the burrowing critters had brought to his hayfields, said that he had been “hoping for another plague.” Advocates, on the other hand, are attempting to shift the entire conversation around prairie dogs, which they treasure as an integral component of a dynamic ecosystem. In the meantime, the region is exploring relocation of prairie dogs as a compromise – with limited success.

In Colorado, a ‘keystone’ species that’s also a pest

Adorable critter or plague-ridden pest? Keystone species or destructive rodent? Depending who you talk to, the prairie dog can be all of the above.

For residents and land managers along Colorado’s Front Range, balancing the competing interests of farmers and ranchers, developers, prairie-dog advocates, and ecologists can be a delicate balance that often gets heated.

Tensions around the prairie dog are rooted in a disconnect between the way wildlife advocates and landowners view ecosystems. Farmers, ranchers, and developers see land as a fixed resource. Their livelihoods depend on the ability to control the landscape. Prairie dogs disrupt that control. From the ecologist's perspective, however, the prairie dog and its ever-shifting network of burrows are emblematic of a dynamic ecosystem.

“What it boils down to is values,” says Rob Alexander, an agricultural resources supervisor with Boulder County Parks & Open Space, who oversees the removal of prairie dog colonies on county lands used for agriculture. “We try to achieve a balance among the many legitimate uses of open space…. But it doesn’t mean everyone will be happy all the time.”

At a stakeholder meeting Boulder County held last week to update residents about prairie dog management and some potential changes to policy, very few people in the packed room were happy.

Local farmers complained about county land they lease, designated as “no prairie dog” zones, where “out of control” colonies persist and turn “grassland into moonscapes.”

Terry Parrish, a rancher who has raised livestock and hay on his Boulder County ranch since 1958, says that when he looks at prairie dogs he sees the holes that clear out the landscape and destroy his hay fields. “I was hoping for another plague,” he says, referring to the recurrent illnesses that have been a major threat to prairie dogs in recent years.

Prairie dog advocates, meanwhile, expressed outrage about the more than 18,000 burrows on which the county used lethal measures (numbers which include multiple treatments on the same burrows and are not analogous with the number of animals killed) and questioned why more colonies couldn’t be left alone, or relocated to more suitable lands, and why tax dollars were used to kill them.

“When you use the word ‘infestation,’ that bothers me,” one young woman told county officials. “We’re the ones who have invaded and infested the areas where prairie dogs have lived forever.”

But Mr. Alexander says that the people who come to those meetings tend to represent the extremes. He notes that the county has worked hard over the years to come up with a model that takes varying concerns into account, and has learned to work well with some local prairie dog advocacy groups who understand that the species they love can be hard to reconcile with agriculture.

A keystone species

Prairie dogs create a conundrum across the Rocky Mountain West. Their habitat has been drastically reduced, and plague, which came to the region within the last century, has decimated colonies. Most estimates put current occupied habitat at just 2 or 3 percent of historic highs, though the number is significantly higher than its low point in 1961, when just 364,000 acres across the West had black-tailed prairie dogs.

But for many ranchers and farmers, they will always be a pest, and there was widespread relief when the US Fish and Wildlife Service decided eight years ago that they don’t warrant any protection as threatened or endangered under the Endangered Species Act.

Their intricate networks of burrows can disrupt agriculture and irrigation and injure horses or cows, but ecologists note that the prairie dogs are also a critical species – a “keystone” species upon which many others depend – that has lost almost all their historic habitat.

Joanne Petersen, an activist who came to the meeting and who has lived in Boulder County for more than 20 years, suggested that the killing of prairie dog colonies may be driving away birds of prey. They’re an important food source for many raptors, and are also critical to species like the burrowing owl, which doesn’t eat them, but nests in their burrows.

“They’re an important wildlife species, but I also think of them as a ‘habitat type’,” says Tina Jackson, species conservation coordinator with Colorado Parks and Wildlife, comparing them to beavers or coral – other animals that actually create a unique habitat. “That’s what prairie dogs do on the landscape, and they’ve always done that…. They really are one of those species – when we lose them, we lose a whole bunch of other things.”

That’s one reason why Colorado and several other states closely monitor their prairie dog habitat, trying to ensure that numbers never get too low. The most recent survey, completed a year ago, found that prairie dogs inhabit about 500,000 acres in Colorado, a figure that puts it just over the threshold of “vulnerable” and into “abundant” territory.

A murky path forward

But part of the problem in places like Boulder County isn’t just how many prairie dogs there are, but where those colonies are located. Even as farmers are angrily demanding speedier removal of unwanted colonies, the county is trying to encourage prairie dogs in grasslands large enough to eventually support black-footed ferret reintroduction. The carnivorous ferret – once thought extinct and still one of the most endangered animals in North America – subsists almost exclusively on prairie dogs, and reintroductions require at least 1,500 contiguous acres of prairie dog-inhabited grasslands – difficult to find with increasingly fragmented lands.

Given that goal, many prairie dog advocates argue that the colonies targeted for extermination should instead be relocated to the grasslands where prairie dogs are needed if ferrets can live there.

“They’re all agreed they want black-footed ferret reintroduction,” says Deanna Meyer, director of Prairie Protection Colorado. “You need to have a lot of prairie dogs for that.”

Ms. Meyer got started in advocacy when she noticed that prairie dog colonies near where she lived, in Castle Rock, Colo., were disappearing. When a mall developer announced plans to destroy the largest prairie dog colony left on the Front Range, she started a campaign to stop it, ultimately saving several hundred which got relocated and are currently thriving, she says.

Relocation efforts, however, are costly and not always effective. At the local county meeting, senior wildlife biologist Susan Spaulding described a relocation of 86 prairie dogs last year that ultimately cost $163 per prairie dog. And the most successful reintroductions require existing empty burrows, which don’t currently exist on the properties targeted for black-footed ferrets.

Meyer would like to see such relocation efforts used more often, and hopes for a shift in thought in which prairie dogs are no longer treated as pests. Noting the reputation the area has for strong environmental activism, she says, “Boulder is the place to change that, because it could happen.”

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

US response to China’s techno threats: Do what you do well

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By The Monitor's Editorial Board

China keeps providing new evidence that it sees itself in a global contest with the United States for technological superiority. Yet the US must be careful in how it reacts to China’s competition. Preventing theft of intellectual property by China is essential, of course. And the US government should be increasing support of fundamental research, not cutting it. But in some responses, the US may risk undercutting the very values that have promoted innovative thinking and that help the US maintain its status as the world’s technological leader. Fear of China’s tactics must be checked by reminding Americans to reinforce their legacy of ingenuity, freedom of thought, and a generous tolerance of failure in the race for new discoveries. The US still ranks higher than China in spending on research and development. And American scientific papers tend to be cited more often than Chinese papers. The US also has more agility than China, which has a top-down, government-mandated approach, in quickly changing course with new trends in science. Doing what you do well is still the best strategy.

US response to China’s techno threats: Do what you do well

It is no trade secret that China sees itself in a global contest with the United States for technological superiority. In just the past week, evidence of this competition was made clear in four news stories:

Scientists in China have created two cloned monkeys, a first in research that might lead to human cloning. A federal jury found a Chinese wind turbine manufacturer guilty of stealing technology from a US company. President Trump slapped tariffs on imports of solar panels to counter China’s subsidy of its solar firms. And the National Science Foundation warned in a report that China now publishes more scientific research than the US.

Such news only adds to rising cries in Washington to block Chinese access to American higher education, research labs, and the US market in technology. No American phone company, for example, wants to carry a new smartphone, the Mate 10, made by Chinese giant Huawei. And more US universities are scrutinizing Beijing’s influence over Chinese students on American campuses or restricting access to research labs.

Yet the US must be careful in how it reacts to China’s competition in both basic research and applied sciences. Preventing theft of intellectual property by China is essential, of course, as American inventors must be assured they will reap the benefits of their creativity. And the US government should be increasing support of fundamental research, not cutting it.

But in some responses, the US may risk undercutting the very values that have promoted innovative thinking and that help the US maintain its status as the world’s technological leader. Fear of China’s tactics, in other words, must be checked by reminding Americans to reinforce their legacy of ingenuity, freedom of thought, and a generous tolerance of failure in the race for new discoveries in science and technology.

Creativity “is not a stock of things that can be depleted or worn out, but an infinitely renewable resource that can be constantly improved,” notes a report called the Global Creativity Index by a group of international scholars.

In a recent paper for the nonpartisan Aspen Strategy Group, two former top security officials, John Deutch and Condoleezza Rice, argue that US schools must play to their strengths more than play defense to the Chinese threat.

As Dr. Deutch told the MIT News: “The idea that we should respond to this threat by either restricting access to US universities or keeping our ideas in the United States is completely wrong. We’ll lose the tremendous advantage we have of an open university system if we do that. The only answer is for US universities to do even more in pursuing their great record of being innovative and creative.”

He contends the gains in keeping the current openness in US research will outweigh any losses from theft of technology. “Recognize that you will have some losses, but do what you do well,” Deutch said.

The US still ranks higher than China in spending on research and development. And American scientific papers tend to be cited more often than Chinese papers, a sign of higher quality. The US also has more agility than China, which has a top-down, government-mandated approach, in quickly changing course with new trends in science. Doing what you do well is still the best strategy.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Where our value lies

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 2 Min. )

-

By Mark Swinney

Today’s column explores how we can find our own worth and capabilities in God’s infinite goodness, love, and intelligence, expressed in us.

Where our value lies

Often, society measures our worth by what we have in comparison to other people – for instance, popularity or money – rather than by what we uniquely are. It can be tempting to feel our individual value is defined this way, and that if we don’t measure up in terms of possessions or connections we are inadequate.

Fortunately, there’s a deeper, more encouraging way to think about our worth. A spiritual view of ourselves gives us a very different perspective of where our value lies. In particular, I’ve found that turning humbly and wholeheartedly to God helps us see that we are each infinitely loved.

As a first-grader, I was introduced to this idea of a God who boundlessly loves and values everyone. This was at a time when my parents couldn’t care for me, and I was living with other families. As kind as these others were, it might have been easy to feel like a worthless, throwaway child. Yet I remained happy, which I attribute to the budding sense I had of my value as a child of God. This simple concept gave me confidence and inner joy.

This sense of my and everyone’s worth has remained with me, deepening into a fuller understanding in the years since, as I’ve come to better understand our creator, God, as perfect Spirit. As Spirit is the true source of our existence, it follows that our nature is and remains spiritual, and as the offspring of Spirit’s perfection we can have no inadequate elements. At every moment we are all distinct, individual expressions of God’s presence and goodness. “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” by Monitor founder Mary Baker Eddy, offers readers this healing perspective of ourselves: “Man is God’s reflection, needing no cultivation, but ever beautiful and complete” (p. 527).

This echoes what “a voice from heaven” said about Christ Jesus, according to the Scriptures: “This is my beloved Son, in whom I am well pleased” (Matthew 3:17). It’s enlightening to know that this took place before Jesus had accomplished his great healing works. This points to a worth based on more than what we do humanly. Jesus’ worth was immeasurable, simply because of what Jesus was: the offspring of the boundless good that is God. And while Jesus’ nature as the Son of God was certainly unique, he was showing us what we all are as God’s cherished, precious children.

In God’s infinite goodness, love, and intelligence, expressed in us, we find our own wonderful worth and capabilities. Recognizing and accepting this forever fact can be completely life-changing.

A message of love

A crown to summon spring

A look ahead

Thanks for spending time with us today. Tonight, Calif. Gov. Jerry Brown gives his final State of the State address. Tomorrow, we'll have a story looking at how California has changed during his second turn at the helm.

A note: On Jan. 18, we ran a story in which a girl named Brylie gave her account of an assault by classmates that she endured in the seventh grade, and described coping with its aftermath (“#MeToo goes to school, with an urgent push for rights awareness”). Last week, Brylie’s family posted the Monitor’s story to their social media pages, attracting a range of responses – a local reporter interested to know more, friends sharing supportive messages (and their own stories, in some cases), and two teens from her former high school mocking her and the #MeToo campaign with an offensive photograph. If you would like to share any feedback with Brylie’s family, or alert us to aspects of this topic you’d like to see covered in future Monitor stories, please contact equaled@csmonitor.com.